20 years ago today two pivotal papers were published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The BENESTENT and the Stent Restenosis Study compared balloon angioplasty to coronary stenting in people with stable angina. What people remember is that stents were superior to balloons and the rest as they say is history. But the story is more complex than that as the trials show. Stents had been around since the late 1980's and they were effective in treating acute vessel closure due to balloon-induced dissection. This complication was the Achilles heel of interventional cardiology and led patients to emergency bypass grafting when their coronary artery closed off during or shortly after the procedure. Unfortunately Achilles had two heels and the other one was restenosis. Some people thought that stents might be useful to reduce the rate of restenosis but there was a problem. Stents were metal which required use of combinations of aspirin, dipyridamole, heparin and then for three months warfarin. This therapy exposed the patient to a risk of major bleeding and vascular complications prolonging hospital stay. In those days vascular access was via the femoral artery and the sheaths were about 3mm wide. Read today the results of the trials are interesting. Take the BENESTENT trial, the rate of in-hospital events was similar in both groups (6.2% in the balloon vs. 6.9% in the stent group). There was no difference in the incidence of myocardial infarction or in the need for urgent or elective cardiac surgery or second angioplasty during the hospital stay. Stent thrombosis occurred in 3.5% and subacute vessel closure after balloon angioplasty in 2.7%. The incidence of bleeding and vascular complications was 4 times higher at 13.5% after stent implantation than after balloon angioplasty. Hospital stay was 8.5 days after a stent and 3.1 days after a balloon. Now reading this is I am surprised. Stents were not so much better than plain old balloon angioplasty. Acute vessel occlusion was swapped for stent thrombosis and because of the anticoagulation patients had more complications and stayed much longer in hospital. There was no early gain. 20 years on an a coronary stent is a day case procedure done through a tube less than 2mm wide via the wrist and with a complication rate less than 1% and re-stenosis rates almost as low. The requirement for on site surgery is a thing of the past. The speciality of interventional cardiology is now mature. Where will it be in another 20 years?

0 Comments

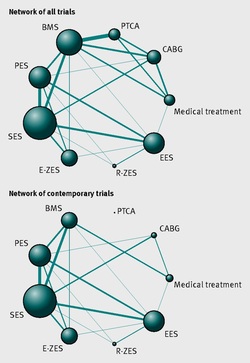

It seemed so simple. If there is a coronary artery narrowing then dilate it with a balloon and insert a stent. The narrowing goes away and the patient is improved. If the artery is the proximal LAD and the narrowing is 90% then surely this must be of benefit, after all, isn't a 90% proximal LAD lesion know as a widow-maker lesion? The problem is that despite the intuitive simplicity of this approach cardiologists have struggled to find the evidence to prove that angioplasty does anything beyond reduce symptoms in stable angina. Only last week a commentary in JAMA Internal Medicine called for better patient information about stenting procedures arguing that many patients consented to these procedures thinking they would not only improve their angina but also reduce risk of death and heart attack. Most recent discussions regarding angioplasty have been reached on the basis of the COURAGE trial. When the COURAGE trial is critiqued you often hear that interventional practice is different and if the trial were done using modern stents then the outcomes would almost certainly be different. These comments are often made by cardiologists keen on promoting angioplasty. However the point is critical since there are major differences between the bare metal stents used in COURAGE and the second generation drug eluting stents used today. No one would argue that the current stents are not vastly superior to bare metal and first generation stents in terms of rates of restenosis and acute stent thrombosis. Earlier this week the BMJ published an important meta-analysis of trials of revascularisation in stable angina. Credit should go to the authors for pulling together and analysing the results of a 100 clinical trials and reviewing the information shown in the Web accessible supplement shows how much work goes into pulling these reviews together. The results are fascinating and at provide evidence to support the argument that judging contemporary practice using historical trials may be misleading. The results showed that when comparing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) to medication there was a 20% reduction in death. Angioplasty but importantly only with new generation (everolimus or zotarolimus) stents reduced deaths by 25-35%. All other interventional procedures had no effect. CABG reduced myocardial infarction by 21% compared to medical treatment and all angioplasty procedures except bare metal stents and paclitaxel eluting stents also showed evidence for possible reduction. Compared with medical treatment, revascularisation with CABG reduce subsequent revascularisation by 84% and stents reduced revascularisation by 66-73% depending on the type of stent used. So for t the moment it reasonable to conclude that in stable coronary disease CABG reduces the risk of death, MI and the need for revascularisation compared with medical treatment. Stent procedures reduce the need for revascularisation but also improve survival when new generation drug eluting stents are used. So at last there is a glimmer of hope that coronary stents do more than just treat angina in stable coronary disease. This will be music to the ears of many interventional cardiologists but whether this glimmer of hope will turn into a bright beacon or a fizzle out will be largely dependent on the results of the ISCHAEMIA trial. In 1958 Mason Sones famously, and apparently accidentally, performed the first coronary angiogram at the Cleveland Clinic. From then on much of the clinical care of patients with ischaemic heart disease was based on research that relied heavily on the visual interpretation of the coronary angiogram. However it wasn't long before papers stared to appear which questioned the accuracy and reproducibility of these visual estimates. One paper from 1976 reported than nearly half the time a group of experienced cardiologists could not agree on the presence of significant coronary artery disease. Other studies followed alleging to to demonstrate the benefits of performing quantitative coronary angiography using computers to assist in the measurement of the degree of narrowing. These methods were more reproducible than eyeballing the angiogram but still there was disagreement and the methodology was time consuming. Take for example this angiogram on shown below. Do you think the this LAD stenosis is flow limiting? Why not vote here and see what others think? By early 1990's the literature on the accuracy of angiogram went quiet. Cardiologists had other things on their mind - namely coronary angioplasty and stenting. Angiography was the test which fuelled the fire of angioplasty and so the problems with assessment of flow limiting lesions and lesion significance drifted into the background. The occulo-stenostic reflex was strong. Cardiologists needed their angiograms too much to call into question the ability of the test to diagnose and classify the severity of the coronary lesions. This was the era of eminence-based medicine when expert opinion trumped anything else. The poor reproducibility and difficulty in assessment of lesion was forgotten.

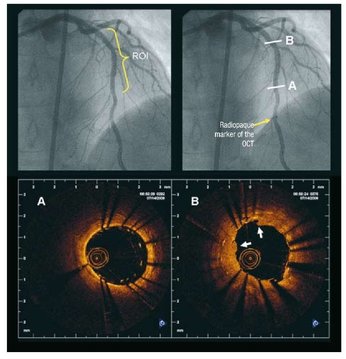

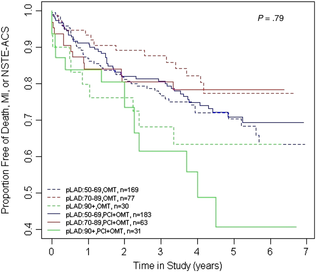

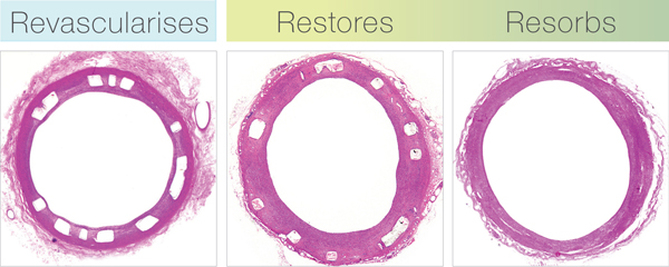

When you learn angiography you quickly realise that the interpretation is difficult. When you work for a number of bosses you start to see a difference in their practice. Some always see a moderate lesion as severe, or a severe lesion as critical. The phrase "the angiogram often underestimates the severity of disease" is often be heard in the catheter lab control room as the guide catheter is being opened ready for angioplasty. Whilst there is usually agreement about the mild (<30%) and severe (>80%) lesions it is the moderate ones which are most difficult and unfortunately most common. As I teach my fellows the percent stenosis is the wrong way to think about lesions, rather we should say whether we believe a lesion to be flow limiting or not. Flow limitation is dependent on the stenosis but also on the reference vessel size, the lesion length, the size of the territory supplied by the vessel and the presence or absence of collaterals. The issue of interpretation is vital to the individual patient since it determines what treatment is recommended, You don't want a cardiologist to put in a stent or offer bypass surgery if your coronary artery lesion is not flow limiting. Recent studies have revealed what we knew all along namely that when coronary artery disease is moderate it is not possible to accurately know by visual assessment whether the lesion(s) are flow limiting or not. We need better methods not based on anatomy but rather on physiology. I have previously written about the RIPCORD trial but recently a large French registry has published its results which support the idea that the angiogram is difficult to interpret and that use of a pressure wire to measure fractional flow reserve (FFR) alters the cardiologists decision making. The R3F study looked at 1000 people having a diagnostic angiogram. The vessels were assessed and significant lesions documented. The patients symptoms and the results of any non-invasive investigations were considered and a recommendation made as to whether the patient should have medical therapy, angioplasty or bypass surgery. After this the cardiologists performed a pressure wire measurement (FFR) of any stenosis. The results were then used to determine whether the stenosis was flow limiting and with this information in hand the treatment recommendation adjusted. So for example if a patient had a 40% stenosis on the angiogram with medical therapy recommended initially but then the pressure wire was significant (e.g. FFR 0.74) the recommended treatment would be to offer an angioplasty. Using the pressure wire data the overall number of people recommended for medical therapy, angioplasty or bypass did not change but the decision for an individual patient changed 43% of the time. Overall the decision changed in 33% of patients initially recommended to have medical therapy and 50% of patients recommended to have angioplasty or bypass surgery. These results are very important for individual patients since the treatment recommendation means the difference between just taking tablets versus having a procedure or an operation. We don't know yet whether a pressure wire guided approach makes a difference to clinical endpoints such as survival, mortality, rates of heart attacks and a large trial is needed to answer this question. For the moment when a moderate stenosis is diagnosed the patient should be asking their cardiologist what is the FFR?  Angiography of the LAD artery & optical coherence tomography Angiography of the LAD artery & optical coherence tomography The universal approach for deployment of a coronary stents is to use high pressure inflations. This is because high-pressure improves stent expansion and apposition and markedly decreases the incidence of acute and subacute stent thrombosis. In contrast there is no standard protocol for the duration of the high-pressure inflation. Often when a stent is placed the inflation pressure tends to gradually decrease over time suggesting that there is on going slow stent expansion. If the stent further expands with the same inflation pressure then a rapid inflation/deflation sequence may not adequately expand the stent even if the final angiogram looks good. It is possible that sustained inflation until pressure stabilizes would result in more optimal stent deployment. The possibility of incomplete strut apposition may also be heightened if inadequate time is allowed for stent expansion. A recent study has looked at 12 patients having single vessel stent interventions using the new technique of optical coherence tomography. This is an ultrasensitive method that can visualise the apposition of individual stent struts. After pre-dilation the lesions were stented with no angiographic residual stenosis after high-pressure stent balloon inflation of relatively short duration (“rapid” inflation) with an average inflation time of 28±17 sec. Following an OCT measurement prolonged inflation was performed. The inflation time was chosen such that the pressure in the inflation device was completely stable for at least 30 seconds. In order to achieve this it required much longer periods of inflation for 206 ± 115 sec. The patients appeared to be stable during this long inflation but what is interesting is that the minimal stent diameter and minimal stent area both increased after prolonged inflation compared with rapid inflation. Stent diameter increased by 9% from 2.75 ± 0.44 to 3.0 ± 0.5 (P < 0.0001) and stent area by 18% from 6.63 ± 1.85 to 7.83 ± 2.45. Not only this but stent strut mal-apposition was halved. This is a small study but important as it makes us think once again that the coronary angiographic results is a relatively crude guide to the apposition of the struts and the overall deployment of a stent. We should consider using both high pressure and longer inflations.  This is the angiogram of a 48 year old man who exercises regularly and has no cardiac symptoms. His story is not uncommon. He has a medical up every 2 years including an exercise stress test. He completes 9 minutes of exercise without symptoms but there are some ECG changes and cardiology referral is recommended. The cardiologist agrees the exercise ECG is abnormal and requires further investigation. In the absence of symptoms or risk factors for coronary artery disease a CT coronary angiogram was recommended. This surprisingly to the patient indicated a stenosis in the proximal LAD which was then confirmed with an invasive angiogram. Now the cardiologist and patient are faced with a decision: What to do next? There are few things cardiologists agree on but I reckon if you showed 10 interventional cardiologist this angiogram they would all say that something must be done. There might be a discussion about the long term pros and cons of drug eluting stents versus surgical revascularisation but most would agree that medical therapy alone in the absence of revascularisation would represent a sub-standard level of care. Most would agree that a 3.5x23mm drug eluting stent could be placed efficiently with very small risk of complication and an excellent result. There would be complete relief of vessel obstruction and at the same time a reduction in patient and physician anxiety. When it comes to the decision to place a stent are we too strongly influenced by our heart rather than our head. Is it a case of emotion trumping science! The COURAGE study compared optimal medical therapy with stenting in patients with significant coronary disease. After 7 years of follow up in COURAGE study was there was no significant difference between stent treatment and medication. But what of patients with 90% stenosis in the proximal LAD the so called "widow-maker" lesion. Surely patients with this pattern of coronary disease benefit from revascularisation?  A recent paper from the COURAGE study looked at just this group of patients and found that there was no significant difference between the patient treated with stents or optimal medical therapy. The figure on the left shows the that the group of patients with >90% stenosis in the proximal LAD did not fair well over the 7 years. The surprising thing is that those treated with angioplasty and bare metal stenting (lowest solid green line) appeared if anything to fair less well than those treated with optimal medical therapy (second lowest green dotted line). The presence of proximal LAD disease as a rationale for favouring stenting was therefore not proven. This finding is provocative and instructive. If you ask interventional cardiologists (and this has been done in focus groups) they will acknowledge that stenting offers no reduction in the risk of death or heart attack in patients with stable coronary artery disease but despite this they generally believe that stenting does benefit such patients. One senior cardiologist said to me that he preferred to treat the cause of coronary artery disease with a stent rather than merely manage the symptoms with tablets. Reasons for performing stenting include belief in the benefits of treating ischaemia, the open artery hypothesis, potential regret for not intervening if a cardiac event could be averted, alleviation of patient anxiety and medico-legal concerns. If asked, most cardiologists believe that the oculo-stenotic reflex prevails and all significant and amenable stenosis should receive intervention even in asymptomatic patients. When cardiologists are challenged about the lack of evidence of adding stenting to optimal medical therapy in preventing future coronary events most still feel that any patient with significant coronary disease should get a stent even whilst acknowledging the evidence. This disconnect between knowledge and behaviour reflects the discordance between cardiologists’ clinical knowledge and their beliefs about the benefits of angioplasty and that non-clinical factors have substantial influence on cardiologists' decision making. So what happened to this patient? I will leave you to decide and to post your thoughts and comments.  The first coronary stent was implanted in 1986 by Dr Ulrich Sigwart. Stents are metal scaffolds which have revolutionised coronary angioplasty. Prior to stents, coronary dissection, caused by balloon angioplasty, usually resulted in an emergency coronary bypass operation or at best a 90% stenosis was reduced to a 40% one. Stents solved these problems but led to different ones. First there was stent thrombosis. Patients were initially treated with aspirin and warfarin to inhibit the clotting pathways but the bleeding problems were terrible. Then we then realised that aspirin could be combined with ticlopidine and subsequently clopidogrel to provide a safe treatment to reduce stent thrombosis but without the bleeding. Then there was the problem of restenosis (re-narrowing) at the site of the coronary stent implant. This led to spot stenting to keep the length of stent as short as possible. After that and thanks to Antonio Colombo and the use of intra-vascular ultrasound we realised that stents needed to be implanted at high to reduce restenosis. However problems with restenosis still existed and cardiologists developed complex treatments such as brachytherapy (intra-arterial radiotherapy) which now have all but disappeared. In the early 2000's we were introduced to the drug eluting stent. First Cypher, then Taxus and then the second generation stents such as Xience, Promus and Integrity Resolute. No longer did interventional cardiologists have to worry about the length of stent they were implanting. Treat from normal vessel to normal vessel became the mantra. But the downside was stent thrombosis, originally thought to just be a short term problem it is clear that it could occur years after stent implantation. Also in some high risk patients such as those with diabetes the restenosis problem has not been completely solved. There are some patients with in-stent, in-stent re-stenosis for which the treatment options are limited. The holy grail of stenting has been seen as the biodegradable or resorbable stent. Implant the stent when it is needed for the first few months and then when it has done its job, like a self absorbing suture, it dissolves away. This sounds an attractive prospect and in 2012 the world of stenting was revolutionised by the entry of the first commercially available biodegradable stent called ABSORB. In the early phase after implantation the ABSORB revascularises like a drug eluting stent. It releases the anti-proliferative drug everolimus to minimise neo-intimal growth and restenosis. During the restoration the scaffold benignly resorbs and the stent gradually ceases to provide luminal support resulting in a discontinuous structure embedded within the coronary artery. As the scaffold degrades, the polymer is converted into lactic acid which is metabolised and is ultimately converted into benign by-products of carbon dioxide and water. Several studies support this concept and indicate that there is no clinical benefit of a permanent stent over time. The ABSORB eliminates the permanent mechanical restraint on the vessel and should allow for more normal blood vessel function. Three-year results from 101 patients in the second stage of the ABSORB trial have shown that the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events was 10% at three years, similar to a comparative set of data with a best-in-class drug eluting stent at the same follow-up period. In a subset of 45 patients, intravascular imaging techniques showed improvements in vessel movement and a 7.2% increase in late lumen gain (an increase in the area within the blood vessel) from measurements taken at one and three years. These findings are unique to the absorbable stent and are not typically observed with metallic stents that cage the vessel. The ABSORB stent is now available and patients interested in receiving it should discuss with their cardiologist to see if they are suitable for the device. References: ABSORB II Trial ABSORB-Extend Trial

The debate over whether patients with 3 vessel coronary artery disease should be treated with multi-vessel stenting (PCI) or coronary bypass surgery (CABG) has raged for the last decade. Stenting only needed to be as good as surgery for it to become the treatment of choice since the procedure is less invasive and the recovery time quicker. Comparison of the two forms of treatment has been difficult because stents have been constantly improved meaning that every trial was out of date compared to currently available technology at the time the results were published. This week the final 5 year results of the SYNTAX trial were published in the Lancet. This trial randomised 1800 patients to stents or surgery. The average age of the patients was 65 years, 75% were men and 25% diabetic. The combined end point included all-cause mortality, stroke, myocardial infarction and repeat revascularisation. The results showed that 26·9% in the CABG group and 37·3% in the PCI group reached that endpoint (p<0·0001). Myocardial infarction was higher in the PCI group (9.7% vs 3·8%; p<0·0001), as was the need for repeat revascularisation (25·9% vs 13.7%; p<0·0001). All-cause death and stroke were not different. So what can we learn from this trial. First the CABG group appear to get continued benefit as time went on. One explanation for this is that since CABG bypasses, any disease progressing in the artery proximal to the insertion point of the bypass graft remains treated which is not the case if a stent has been implanted. This may not be the whole explanation since CABG did not show a benefit over PCI in the left main stem treatment group although there were only 222 patients in this group. Second, SYNTAX acknowledged that not all 3 vessel disease is the same with some patients have discrete, simple lesions and others having very complex disease. Embedded in this trial was a scoring system (www.syntaxscore.com) which allowed a measure of the severity of the coronary artery disease. Treatment of low score (22 or less) or an isolated left main stem stenosis with CABG did not appear to confer an advantage over stents. In contrast an intermediate or high SYNTAX score predicted a significantly worse outcome if treated with stents rather than CABG. The results indicate that patients with simple three vessel disease could reasonably be treated with stents rather than surgery although it is important to remember that the analysis of subgroups in clinical trials is only hypothesis generating. The subgroups do not have enough patients in them to be adequately powered to draw definitive conclusions. Calculation of the SYNTAX Score gives the cardiologist an estimate of the severity of disease and helps feed into the decision making process regarding the best means of revascularisation. The other issue is that of patient choice. More patients randomised to CABG withdrew from the trial compared to PCI. Faced with a decision regarding what treatment to have the patient will have views and these need to be informed by a discussion of the best available evidence. If a patient understands that stents may have a less good outcome they may still decide to have this treatment because it is less invasive than CABG. The SYNTAX trial also leaves open the question of how to manage much older patients where the risk of stroke and mortality is greater. Many patients we currently see are in their late 70s or 80s, often with severe coronary disease and they may be less included to undergo CABG. Also most of the participants in SYNTAX were male and therefore it is difficult to know whether the outcomes for women would be the same. The SYNTAX trial is an important landmark to inform how we should manage severe coronary artery disease. However we need to remember that as cardiologists we treat individual people and the results of the clinical trials present results from pooled groups of patients may not always be representative of the patient in front of us. Coronary artery bypass graft surgery versus percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with three-vessel disease and left main coronary disease: 5-year follow-up of the randomised, clinical SYNTAX trial  It is the ultimate accolade for an inventor or manufacturer when their name becomes part of the language or is used as a verb to describe a action. Examples include Hoover, Xerox and Google. In cardiology the stent, which is used to treat patients with narrowed coronary arteries shares this unique position as a noun and a verb but where did the word stent come from and why are stents called stents? Mosby's medical dictionary defines a stent as "1. a compound used in making dental impressions and medical molds. 2. a mold or device made of stent, used in anchoring skin grafts and for supporting body parts and cavities during grafting of vessels and tubes of the body during surgical anastomosis." In 1856 Dr Charles Stent invented a material made of natural latex mixed with stearine, talc and red dye which resulted in a stable flexible material which could be used to make dental molds. Some years later the famous plastic surgeon Harold Gillies in his 1920 book Plastic Surgery of the Face, wrote "The dental composition used for this purpose is that put forward by Stent, and a mold composed of it, is known us a "Stent." This is probably the first use of Stent's name as a noun. The use of the word stent to describe a scaffold in the vascular system was by Dr Charles Dotter who in 1983 published his report on "Transluminal expandable nitinol coil stent grafting." The first coronary stent was implanted in 1986 by Jacques Puel in Toulouse and together with Ulrich Sigwart they were been credited with developing the concept of the coronary stent. This device is now used in more than 80% of angioplasty procedures and provides a scaffold for the local delivery of drugs to the artery to prevent re-narrowing at the site of implantation. |

Dr Richard BogleThe opinions expressed in this blog are strictly those of the author and should not be construed as the opinion or policy of my employers nor recommendations for your care or anyone else's. Always seek professional guidance instead. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed