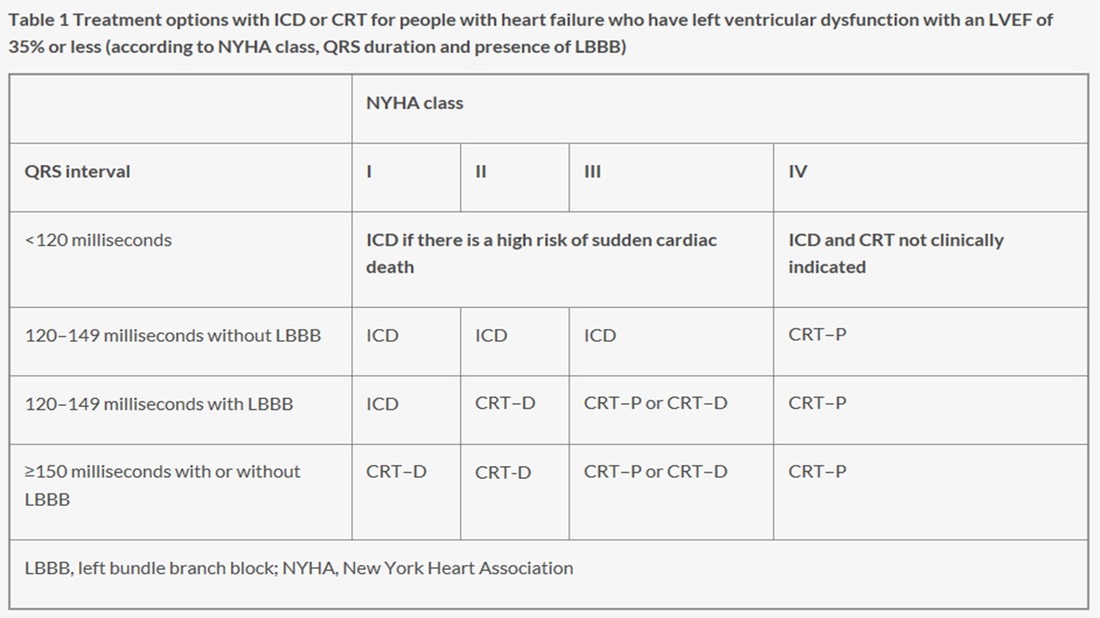

Guidelines are developed to help clinicians practice evidence based medicine. NICE guidelines are regarded as a pre-eminent source of high quality recommendations which have been evaluated carefully and systematically for cost and clinical effectiveness. NICE published their updated guidelines on implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICD) and cardiac resynchronisation (also known as biventricular) pacemakers (CRT) in June 2014. So which cardiac patients should get an ICD? The first recommendations are clear and well established. If a patient has ventricular fibrillation (VF) or ventricular tachycardia (VT) associated with cardiac arrest or sustained VT (i.e. >30 seconds) with syncope or haemodynamic compromise (excluding people with a treatable cause e.g. acute myocardial infarction) or asymptomatic sustained VT and an ejection fraction of <35% and they are not in NYHA class IV heart failure then they should have an ICD. We all agree with that. Putting it simply survivors of VF/VT cardiac arrest or near cardiac arrest and people with sustained VT and a severely impaired left ventricle should have an ICD. However this is a relatively small group of patients compared to the large group with heart failure who if they do have VT it is usually the non-sustained and asymptomatic type. So what does NICE say with regards to them? Here the guidelines get more difficult. NICE say that an ICDs or CRT with defibrillator (CRT‑D) or CRT without defibrillator (CRT‑P) are recommended for people with heart failure who have an EF of <35% depending on their QRS duration on ECG. If the QRS is normal (ie <120msec) then they recommend an ICD if there is a "high risk" of sudden cardiac death. The rest of the table summaries the other recommendations based on the QRS duration and the NYHA class of heart failure. I want to deal with this first group. The narrow QRS group (<120msec) who have an EF<35%. NICE recommend implanting an ICD if there is a high risk of sudden cardiac death but they don't define high risk. How does the cardiologist identify these high risk patients then? Here we move from evidence to eminence based medicine. The guidelines committee apparently explored approaches to defining high risk people with normal QRS duration. They are not the first to try and do this. Others have an have been unsuccessful. Apparently they concluded that although age and sex were important there were other factors which also played a role. That is not a surprising conclusion that even a non-expert might also reach. They thought that the degree of left ventricular impairment, a history of ischaemic heart disease and how much myocardial scar was present might play a role in increasing risk and possibly factors such as your BNP level might be useful. Again it all valid thoughts but unhelpful in making a decision. I guess there was a lot of discussion but no-one on the committee could agree on how you could tell a high risk patient from a lower risk patient.

Perhaps it time for some pragmatism. You want to implant an ICD in a patient at high risk of sudden cardiac death but you don't have a good way of identifying these patients. The outcome you are trying to prevent is very serious, occurs suddenly and unpredictably. If it happens you don't usually get a second chance to treat it. This means your strategy for prevention will need to be deployed with a very high sensitivity to treat and by definition you will need to accept a lower specificity. Thinking of it a different way if the treatment was a tablet you would put everyone on it because the thing you are trying to prevent is so serious and you only get one chance to do it. That must be the only sensible approach. For people with EF<35% the question is Why shouldn't they have an ICD?

1 Comment

|

Dr Richard BogleThe opinions expressed in this blog are strictly those of the author and should not be construed as the opinion or policy of my employers nor recommendations for your care or anyone else's. Always seek professional guidance instead. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed