20 years ago today two pivotal papers were published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The BENESTENT and the Stent Restenosis Study compared balloon angioplasty to coronary stenting in people with stable angina. What people remember is that stents were superior to balloons and the rest as they say is history. But the story is more complex than that as the trials show. Stents had been around since the late 1980's and they were effective in treating acute vessel closure due to balloon-induced dissection. This complication was the Achilles heel of interventional cardiology and led patients to emergency bypass grafting when their coronary artery closed off during or shortly after the procedure. Unfortunately Achilles had two heels and the other one was restenosis. Some people thought that stents might be useful to reduce the rate of restenosis but there was a problem. Stents were metal which required use of combinations of aspirin, dipyridamole, heparin and then for three months warfarin. This therapy exposed the patient to a risk of major bleeding and vascular complications prolonging hospital stay. In those days vascular access was via the femoral artery and the sheaths were about 3mm wide. Read today the results of the trials are interesting. Take the BENESTENT trial, the rate of in-hospital events was similar in both groups (6.2% in the balloon vs. 6.9% in the stent group). There was no difference in the incidence of myocardial infarction or in the need for urgent or elective cardiac surgery or second angioplasty during the hospital stay. Stent thrombosis occurred in 3.5% and subacute vessel closure after balloon angioplasty in 2.7%. The incidence of bleeding and vascular complications was 4 times higher at 13.5% after stent implantation than after balloon angioplasty. Hospital stay was 8.5 days after a stent and 3.1 days after a balloon. Now reading this is I am surprised. Stents were not so much better than plain old balloon angioplasty. Acute vessel occlusion was swapped for stent thrombosis and because of the anticoagulation patients had more complications and stayed much longer in hospital. There was no early gain. 20 years on an a coronary stent is a day case procedure done through a tube less than 2mm wide via the wrist and with a complication rate less than 1% and re-stenosis rates almost as low. The requirement for on site surgery is a thing of the past. The speciality of interventional cardiology is now mature. Where will it be in another 20 years?

0 Comments

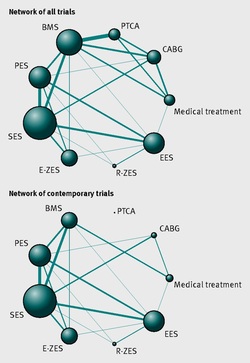

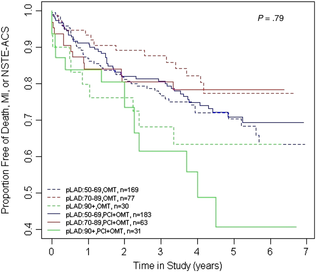

It seemed so simple. If there is a coronary artery narrowing then dilate it with a balloon and insert a stent. The narrowing goes away and the patient is improved. If the artery is the proximal LAD and the narrowing is 90% then surely this must be of benefit, after all, isn't a 90% proximal LAD lesion know as a widow-maker lesion? The problem is that despite the intuitive simplicity of this approach cardiologists have struggled to find the evidence to prove that angioplasty does anything beyond reduce symptoms in stable angina. Only last week a commentary in JAMA Internal Medicine called for better patient information about stenting procedures arguing that many patients consented to these procedures thinking they would not only improve their angina but also reduce risk of death and heart attack. Most recent discussions regarding angioplasty have been reached on the basis of the COURAGE trial. When the COURAGE trial is critiqued you often hear that interventional practice is different and if the trial were done using modern stents then the outcomes would almost certainly be different. These comments are often made by cardiologists keen on promoting angioplasty. However the point is critical since there are major differences between the bare metal stents used in COURAGE and the second generation drug eluting stents used today. No one would argue that the current stents are not vastly superior to bare metal and first generation stents in terms of rates of restenosis and acute stent thrombosis. Earlier this week the BMJ published an important meta-analysis of trials of revascularisation in stable angina. Credit should go to the authors for pulling together and analysing the results of a 100 clinical trials and reviewing the information shown in the Web accessible supplement shows how much work goes into pulling these reviews together. The results are fascinating and at provide evidence to support the argument that judging contemporary practice using historical trials may be misleading. The results showed that when comparing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) to medication there was a 20% reduction in death. Angioplasty but importantly only with new generation (everolimus or zotarolimus) stents reduced deaths by 25-35%. All other interventional procedures had no effect. CABG reduced myocardial infarction by 21% compared to medical treatment and all angioplasty procedures except bare metal stents and paclitaxel eluting stents also showed evidence for possible reduction. Compared with medical treatment, revascularisation with CABG reduce subsequent revascularisation by 84% and stents reduced revascularisation by 66-73% depending on the type of stent used. So for t the moment it reasonable to conclude that in stable coronary disease CABG reduces the risk of death, MI and the need for revascularisation compared with medical treatment. Stent procedures reduce the need for revascularisation but also improve survival when new generation drug eluting stents are used. So at last there is a glimmer of hope that coronary stents do more than just treat angina in stable coronary disease. This will be music to the ears of many interventional cardiologists but whether this glimmer of hope will turn into a bright beacon or a fizzle out will be largely dependent on the results of the ISCHAEMIA trial.  When discussing revascularisation procedures (coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) or stents), patients often ask: How long will my bypass/stent last? There is no easy answer to this question. I have patients with stents implanted 20 years ago which are still working perfectly and also known people who had a CABG in the 1980’s where all the grafts are in excellent condition. Conversely patients may return rapidly after surgery with graft failure or develop critical in-stent restenosis within months of angioplasty. Results from randomised clinical trials of stents versus surgery such as the SOS and SYNTAX favour CABG as superior treatment compared to stenting. CABG appears to be associated with a lower likelihood of repeat revascularisation. But there is a problem with these trials. Inherent clinician bias usually favours repeating angiograms in patients treated with stents who develop symptoms after the procedure compared to those patients who have received treatment with CABG. Since the clinician and the patients are not blinded to the original treatment this belief that surgery is a more robust and reliable method of revascularisation is likely to increases the rate of repeat angiography which leads to a high rate of repeat revascularisation. So what is the rate of CABG vein graft occlusion? A recent paper looked at this question in 1829 patients who had a coronary angiogram within 12-18 months after CABG and were then followed for a further 3 years. Within 18 months after CABG 43% of patients (770/1829) had at least one vein graft occlusion. The identification of this occlusion was associated with a 5-fold increase in repeat revascularisations procedures although it did not lead to a higher number of heart attacks or deaths compared to patients whose grafts were all patent. There rate of revascularization procedures within 14 days of angiography demonstrating a vein graft occlusion shows the power of the occlulostenotic reflex as discussed before in an earlier blog. Since the angiography was protocol, and not symptom, driven the identification of the stenosis on an angiogram was enough to result in a repeat revascularisation procedure with a stent. What is the reason for the graft occlusion? Surgical technique, quality of the vein graft and target vessels or is it perhaps that the stenosis didn’t need bypassing in the first place. The FAME study using pressure wire showed that 20% of coronary arteries with significant stenosis (70-90%) on an angiogram were not associated with ischemia and in such cases vein graft failure could easily ay occur without clinical consequence or symptoms. So when answering the question about the longevity of a bypass graft we should say that nearly half of patients will lose at least one graft within 18 months of surgery but the chance that it will cause harm to the patient is low unless someone discovers that it is occluded.  Earlier this week saw the sudden death of the union boss Bob Crow. The headline from the Evening Standard screamed: "Tube Union boss Dies of Heart Attack." He was just 52 years old. Despite advances in treatment of acute heart attacks with primary angioplasty many patients still die suddenly within minutes of the onset of chest pain. The problem with coronary disease is that sometimes the first symptom to alert the patient that something's wrong is when a lethal heart attack strikes. Many patients have not experienced symptoms before that to alter them that there might be a problem. Coronary heart disease does not really have any outward physical signs and so detecting people who may have developed the condition but who have no symptoms is difficult. We recognise various risk factors for heart disease such as age, male sex, high blood pressure, diabetes, cigarette smoking, cholesterol and family history but many people have risk factors and do not develop coronary disease. What would be helpful is an outward physical sign, easily detected, which could alter doctors and patients alike that they might not just be at risk of heart disease but more importantly that they might already have diseased arteries. Over 40 years ago in Dr Sanders Frank reported just such a sign which is today has been forgotten by many doctors and is virtually unknown to patients. In a brief letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine Dr Frank reported his observations of a prominent crease in the ear lobe which was usually present in patients he had seen with coronary artery disease. Initially he reported findings in just 20 patients but since then many studies have been completed confirming his findings. One study of over 1000 unselected patients looked at the presence of a diagonal ear lobe crease and coronary artery disease and found a high degree of correlation independent of age. In this study 112 consecutive patients had coronary angiography and an ear lobe creases was the best predictor of narrowed coronary arteries. Other studies followed which confirmed that ear crease was much more common in patients hospitalized after a heart attack compared to age-matched control subjects with no evidence of cardiac disease. These findings have also been repeated more recently using CT scans to detect coronary artery disease. The presence of an ear lobe crease should alert doctors and patients to the possible presence of coronary heart disease. I don't know anything about Bob Crow's medical history but the picture above a close up of his ear with the ear lobe crease clearly visible. So my advice is clear - look at your ears and if your are under 60 years old and see this change mention it to your doctor.  This is the angiogram of a 48 year old man who exercises regularly and has no cardiac symptoms. His story is not uncommon. He has a medical up every 2 years including an exercise stress test. He completes 9 minutes of exercise without symptoms but there are some ECG changes and cardiology referral is recommended. The cardiologist agrees the exercise ECG is abnormal and requires further investigation. In the absence of symptoms or risk factors for coronary artery disease a CT coronary angiogram was recommended. This surprisingly to the patient indicated a stenosis in the proximal LAD which was then confirmed with an invasive angiogram. Now the cardiologist and patient are faced with a decision: What to do next? There are few things cardiologists agree on but I reckon if you showed 10 interventional cardiologist this angiogram they would all say that something must be done. There might be a discussion about the long term pros and cons of drug eluting stents versus surgical revascularisation but most would agree that medical therapy alone in the absence of revascularisation would represent a sub-standard level of care. Most would agree that a 3.5x23mm drug eluting stent could be placed efficiently with very small risk of complication and an excellent result. There would be complete relief of vessel obstruction and at the same time a reduction in patient and physician anxiety. When it comes to the decision to place a stent are we too strongly influenced by our heart rather than our head. Is it a case of emotion trumping science! The COURAGE study compared optimal medical therapy with stenting in patients with significant coronary disease. After 7 years of follow up in COURAGE study was there was no significant difference between stent treatment and medication. But what of patients with 90% stenosis in the proximal LAD the so called "widow-maker" lesion. Surely patients with this pattern of coronary disease benefit from revascularisation?  A recent paper from the COURAGE study looked at just this group of patients and found that there was no significant difference between the patient treated with stents or optimal medical therapy. The figure on the left shows the that the group of patients with >90% stenosis in the proximal LAD did not fair well over the 7 years. The surprising thing is that those treated with angioplasty and bare metal stenting (lowest solid green line) appeared if anything to fair less well than those treated with optimal medical therapy (second lowest green dotted line). The presence of proximal LAD disease as a rationale for favouring stenting was therefore not proven. This finding is provocative and instructive. If you ask interventional cardiologists (and this has been done in focus groups) they will acknowledge that stenting offers no reduction in the risk of death or heart attack in patients with stable coronary artery disease but despite this they generally believe that stenting does benefit such patients. One senior cardiologist said to me that he preferred to treat the cause of coronary artery disease with a stent rather than merely manage the symptoms with tablets. Reasons for performing stenting include belief in the benefits of treating ischaemia, the open artery hypothesis, potential regret for not intervening if a cardiac event could be averted, alleviation of patient anxiety and medico-legal concerns. If asked, most cardiologists believe that the oculo-stenotic reflex prevails and all significant and amenable stenosis should receive intervention even in asymptomatic patients. When cardiologists are challenged about the lack of evidence of adding stenting to optimal medical therapy in preventing future coronary events most still feel that any patient with significant coronary disease should get a stent even whilst acknowledging the evidence. This disconnect between knowledge and behaviour reflects the discordance between cardiologists’ clinical knowledge and their beliefs about the benefits of angioplasty and that non-clinical factors have substantial influence on cardiologists' decision making. So what happened to this patient? I will leave you to decide and to post your thoughts and comments. |

Dr Richard BogleThe opinions expressed in this blog are strictly those of the author and should not be construed as the opinion or policy of my employers nor recommendations for your care or anyone else's. Always seek professional guidance instead. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed