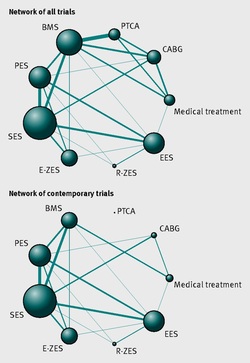

It seemed so simple. If there is a coronary artery narrowing then dilate it with a balloon and insert a stent. The narrowing goes away and the patient is improved. If the artery is the proximal LAD and the narrowing is 90% then surely this must be of benefit, after all, isn't a 90% proximal LAD lesion know as a widow-maker lesion? The problem is that despite the intuitive simplicity of this approach cardiologists have struggled to find the evidence to prove that angioplasty does anything beyond reduce symptoms in stable angina. Only last week a commentary in JAMA Internal Medicine called for better patient information about stenting procedures arguing that many patients consented to these procedures thinking they would not only improve their angina but also reduce risk of death and heart attack. Most recent discussions regarding angioplasty have been reached on the basis of the COURAGE trial. When the COURAGE trial is critiqued you often hear that interventional practice is different and if the trial were done using modern stents then the outcomes would almost certainly be different. These comments are often made by cardiologists keen on promoting angioplasty. However the point is critical since there are major differences between the bare metal stents used in COURAGE and the second generation drug eluting stents used today. No one would argue that the current stents are not vastly superior to bare metal and first generation stents in terms of rates of restenosis and acute stent thrombosis. Earlier this week the BMJ published an important meta-analysis of trials of revascularisation in stable angina. Credit should go to the authors for pulling together and analysing the results of a 100 clinical trials and reviewing the information shown in the Web accessible supplement shows how much work goes into pulling these reviews together. The results are fascinating and at provide evidence to support the argument that judging contemporary practice using historical trials may be misleading. The results showed that when comparing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) to medication there was a 20% reduction in death. Angioplasty but importantly only with new generation (everolimus or zotarolimus) stents reduced deaths by 25-35%. All other interventional procedures had no effect. CABG reduced myocardial infarction by 21% compared to medical treatment and all angioplasty procedures except bare metal stents and paclitaxel eluting stents also showed evidence for possible reduction. Compared with medical treatment, revascularisation with CABG reduce subsequent revascularisation by 84% and stents reduced revascularisation by 66-73% depending on the type of stent used. So for t the moment it reasonable to conclude that in stable coronary disease CABG reduces the risk of death, MI and the need for revascularisation compared with medical treatment. Stent procedures reduce the need for revascularisation but also improve survival when new generation drug eluting stents are used. So at last there is a glimmer of hope that coronary stents do more than just treat angina in stable coronary disease. This will be music to the ears of many interventional cardiologists but whether this glimmer of hope will turn into a bright beacon or a fizzle out will be largely dependent on the results of the ISCHAEMIA trial.

2 Comments

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is an important and preventable cause of stroke. If AF is detected then a patient will usually be advised to go onto anticoagulation which reduces the risk of stroke by about 70%. Some patients will have paroxysmal AF (PAF) which comes and goes interspersed by normal heart rhythm. PAF is defined as 30 seconds or more of AF and the risk of stroke is the same as with persistent AF. The ASSERT trial tried to determine how much PAF is necessary to increase the stroke risk and the results suggest that as little as 6 minutes of AF over a period of 3 months increases stroke risk by 2.5 fold. After a stroke it is routine to do an 12 lead ECG to assess the cardiac rhythm and if this is normal then a longer period of heart monitoring would be performed to look for evidence of PAF. The question is however how long should the monitoring be done for to stand a good chance of detect PAF? Is 24h enough, or should it be a week or a month or even longer. Two papers published this week in the New England Journal of Medicine have tried to address this question. The EMBRACE study compared a standard approach with 24h ECG monitor to a 30 day cardiac event recorder. 572 patients with apparently normal heart rhythm with a previous stroke in the last 6 months were randomly assigned to either 24h or 30 days of monitoring. In the group monitored for 24h just 3.2% of people had AF detected whereas in the group monitored for 30 days AF was detected in 16.1%. This meant that for every 8 people screened for the longer period 1 extra case of PAF was detected. Once AF was detected it led to a change of treatment for the patients with antiplatelet drugs being switched to anticoagulants which are much more effective at reducing recurrent stroke. In the CRYSTAL AF study patients were randomly assigned to either having a loop recorder implanted or standard care. After 6 months PAF has been detected in 8.9% of patients with the ILR compared to 1.4% in the control group and by 12 months this had increased to 12.4% in the ILR and 2% in the control group. There is a difference in the AF detection rate between the two studies which is probably due to the EMBRACE trial having an older population with more patients suffering from hypertension and diabetes. What is clear however is that the longer the period of monitoring the more cases of undiagnosed AF are detected. Since this has a profound effect on management of the patient these findings are very important. There are some practical problems with monitoring patients for 30 days due to the ability to comply with the need for electrodes of the chest. The EMBRACE study used a dry electrode chest belt which has better tolerability and less skin irritation than traditional electrodes. The ILR technique is attractive particularly and with the advent of virtually injectable devices such as the REVEAL LINQ but the cost of these devices might be seen as prohibitive if the technology was applied to every patient with a stroke. Perhaps though when a cost-effectiveness analysis is performed and the number of recurrent strokes prevented is factored in this type of monitoring device would pay for itself. If you take the parallel situation of a patient with a heart attack we think nothing of implanting several drug eluting stents which cost thousands of pounds in order to prevent a recurrent admission to hospital with chest pain or a non-fatal heart attack. What then of spending a similar amount to prevent a stroke? These new studies are challenging the current practice of accepting a short period of monitoring when looking for AF. In this situation absence of evidence of AF should not be taken as evidence of absence and it looks as though a more prolonged period of monitoring is likely to be beneficial.  This was also published on the British Geriatric Society Blog site If you watched the news this week you might have thought that the only recommendation in the NICE Atrial Fibrillation Guideline was that doctors should not prescribe aspirin to prevent strokes. In fact most cardiologists and geriatricians stopped using aspirin for this condition several years ago and the NICE recommendation simply reaffirms those issued previously by other professional societies such as the European Society of Cardiology. The real story behind the guidelines was, in my opinion, nothing to do with medication or rate versus rhythm but rather the importance of delivering a personalised package of care for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). Recognising that AF is a long term health condition there is emphasis on the importance of shared decision making processes particularly around anticoagulation. Alongside the guideline NICE published a Patient Decision Aid to assist with this process. The intention behind this is good but having shown the 36 page decision aid document to several patients today they were overwhelmed by the volume of information they were expected to digest. The aid includes much information that would not be relevant to the individual patient since it tries to cover the risks and benefit of all patients with various stroke and bleeding risks. It uses Cates plots to try and aid the decision making process but each chart has 1000 faces and only looks at the risks/benefits over one year so the faces benefiting from treatment are swamped by hundreds of faces not expecting any benefit. On a practical note NICE assumes that clinicians will have ready access to a colour printer otherwise the red/greens charts look somewhat monotone. The comparison of this decision aid with the highly professional and dynamic way information is presented on the JBS3 risk calculator website is striking and NICE need to up their game to make this and further decision aids much more user friendly. Summarising the information on two sides of A4 is aspirational but possible as has been done with other documents on breast and prostate cancer screening as has been promoted by the work of Gerd Gigerenzer. The guideline emphasises that the patient’s decision regarding anticoagulation will be affected by their own attitude towards risk and NICE say that if patients are provided with the appropriate information about the pros and cons they should be able to decide for themselves about whether to have treatment with anticoagulation or not. This removes the recommendation or opinion of the healthcare provider from the consultation and devolves the decision making to the patient. This represents a change in the doctor patient relationship and the dynamics of the consultation. In my experience, patients want to know the pros and cons of a particular treatment but are also interested in the opinion of the healthcare professional especially if they are well known and trusted. In everyday life we use rules of thumb – so called heuristics and recommendations from friends and family feed into the ability to make complex decisions. Often personal experience and anecdotes are trusted in preference to scientific evidence. To devolve the decision making completely to the patient might be seen as convenient for the healthcare professional. If the patient chooses anticoagulation and then bleeds – it was the patient’s decision to start the treatment, not the doctors. If the patient decides not to take anticoagulation and has a stroke then again it was their decision. In practice clinical medicine is complex and the interaction between a patient and an experienced clinician vital to make a detailed and appropriate assessment. Although stroke and bleeding risk can be calculated using scoring systems these measures are not perfect and derive from large populations which do not necessarily apply to the patient in the consulting room who may have complex multisystem disease and polypharmacy. The risk assessment tools are a starting point of the conversation about treatments. NICE should be commended for placing the patient’s involvement in deciding their management of AF centre stage. This is a clear move in the right direction for patients and should improve both outcomes of this common condition. In 1958 Mason Sones famously, and apparently accidentally, performed the first coronary angiogram at the Cleveland Clinic. From then on much of the clinical care of patients with ischaemic heart disease was based on research that relied heavily on the visual interpretation of the coronary angiogram. However it wasn't long before papers stared to appear which questioned the accuracy and reproducibility of these visual estimates. One paper from 1976 reported than nearly half the time a group of experienced cardiologists could not agree on the presence of significant coronary artery disease. Other studies followed alleging to to demonstrate the benefits of performing quantitative coronary angiography using computers to assist in the measurement of the degree of narrowing. These methods were more reproducible than eyeballing the angiogram but still there was disagreement and the methodology was time consuming. Take for example this angiogram on shown below. Do you think the this LAD stenosis is flow limiting? Why not vote here and see what others think? By early 1990's the literature on the accuracy of angiogram went quiet. Cardiologists had other things on their mind - namely coronary angioplasty and stenting. Angiography was the test which fuelled the fire of angioplasty and so the problems with assessment of flow limiting lesions and lesion significance drifted into the background. The occulo-stenostic reflex was strong. Cardiologists needed their angiograms too much to call into question the ability of the test to diagnose and classify the severity of the coronary lesions. This was the era of eminence-based medicine when expert opinion trumped anything else. The poor reproducibility and difficulty in assessment of lesion was forgotten.

When you learn angiography you quickly realise that the interpretation is difficult. When you work for a number of bosses you start to see a difference in their practice. Some always see a moderate lesion as severe, or a severe lesion as critical. The phrase "the angiogram often underestimates the severity of disease" is often be heard in the catheter lab control room as the guide catheter is being opened ready for angioplasty. Whilst there is usually agreement about the mild (<30%) and severe (>80%) lesions it is the moderate ones which are most difficult and unfortunately most common. As I teach my fellows the percent stenosis is the wrong way to think about lesions, rather we should say whether we believe a lesion to be flow limiting or not. Flow limitation is dependent on the stenosis but also on the reference vessel size, the lesion length, the size of the territory supplied by the vessel and the presence or absence of collaterals. The issue of interpretation is vital to the individual patient since it determines what treatment is recommended, You don't want a cardiologist to put in a stent or offer bypass surgery if your coronary artery lesion is not flow limiting. Recent studies have revealed what we knew all along namely that when coronary artery disease is moderate it is not possible to accurately know by visual assessment whether the lesion(s) are flow limiting or not. We need better methods not based on anatomy but rather on physiology. I have previously written about the RIPCORD trial but recently a large French registry has published its results which support the idea that the angiogram is difficult to interpret and that use of a pressure wire to measure fractional flow reserve (FFR) alters the cardiologists decision making. The R3F study looked at 1000 people having a diagnostic angiogram. The vessels were assessed and significant lesions documented. The patients symptoms and the results of any non-invasive investigations were considered and a recommendation made as to whether the patient should have medical therapy, angioplasty or bypass surgery. After this the cardiologists performed a pressure wire measurement (FFR) of any stenosis. The results were then used to determine whether the stenosis was flow limiting and with this information in hand the treatment recommendation adjusted. So for example if a patient had a 40% stenosis on the angiogram with medical therapy recommended initially but then the pressure wire was significant (e.g. FFR 0.74) the recommended treatment would be to offer an angioplasty. Using the pressure wire data the overall number of people recommended for medical therapy, angioplasty or bypass did not change but the decision for an individual patient changed 43% of the time. Overall the decision changed in 33% of patients initially recommended to have medical therapy and 50% of patients recommended to have angioplasty or bypass surgery. These results are very important for individual patients since the treatment recommendation means the difference between just taking tablets versus having a procedure or an operation. We don't know yet whether a pressure wire guided approach makes a difference to clinical endpoints such as survival, mortality, rates of heart attacks and a large trial is needed to answer this question. For the moment when a moderate stenosis is diagnosed the patient should be asking their cardiologist what is the FFR?  Dogs are out of control. Between 2009 and 2011 there was a 13% increase in the number of admissions to hospital due to dog attacks. A serious problem, dogs and their owners are out of control. Action must be taken! But what does this 13% actually mean? What is it 13% of? In 2009/10 there were 5,837 admissions to hospital due to dog attacks. In 2011/12 the number was 6,580. That's an increase in 13 % or 743 cases. Is this a big problem for the NHS or society in general? In order to work that out we need to know the number of hospital admissions. In 2009/10 there were 6,430,372. This means that dog attacks represent 1 in 10,000 admissions. So a 13% increase is an increase from 0.0118% to 0.103%. This means that we are dealing with very small numbers which are unlikely to be of much clinical significance. The same caution needs to be applied to other hospital statistics. Take for example the current debate about weekend working in the NHS. This has been fuelled by studies indicating that the risk of dying is greater if you are admitted to hospital at the weekend compared to a weekday. This is shown in a recent study which reported that the 30 day mortality was 16% greater if you are admitted at the weekend. But what does this mean? Is it for every 100 deaths during the week there are 116 at the weekend. We need to analyse the data further. 14.2 million people were admitted to hospital in 2009/10 and 187,337 died. This means that 1.3% of people admitted died. The rate of death if you were admitted at the weekend was 16% higher, in other words about 0.21%. This means that the chance of dying within 30 days of admission is 0.21% higher if you are admitted at the weekend compared to a weekday. Alternatively there is a 98% chance of survival if admitted on a weekday compared to a 97.68% chance if admitted at the weekend. Is this clinically significant? I would welcome your comments. |

Dr Richard BogleThe opinions expressed in this blog are strictly those of the author and should not be construed as the opinion or policy of my employers nor recommendations for your care or anyone else's. Always seek professional guidance instead. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed