|

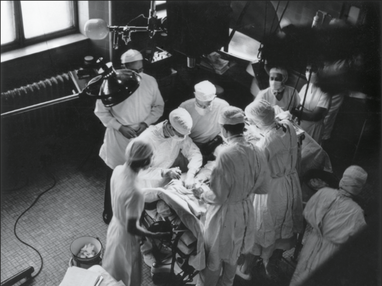

On the 29th October 1944 the first cardiac operation was performed at the Johns Hopkins Hospital for the treatment of congenital heart disease. Dr Alfred Blalock, the Chief of Surgery, carried out a pioneering surgical procedure designed to palliate a condition called Tetralogy of Fallot. This complex condition is characterised by a narrowing in the outflow tract of the right ventricle, thickening of the right ventricle, a ventricular septal defect and an over-riding aorta. In essence the blood flow to the lung is severely compromised and babies born with this condition are often deeply cyanosed and therefore known as "blue-babies." In the 1930’s the management of a blue baby was to place them in an oxygen tent. Children were advised to assume a squatting position to reduce venous return to the heart, and to try and keep as quiet and calm as possible to reduce infundibular spasm. The prognosis was terrible and the paediatric cardiologist at Johns Hopkins, Dr Helen Taussig, had to simply watch babies and children die. It was known that children with Fallot's who also had a patent ductus arteriosus were less cyanosed and this led to the idea of whether it might be possible to create a shunt between a great vessel and the pulmonary artery in order to supply blood to the lung. After painstaking laboratory work this resulted in the introduction of what is commonly called the "Blalock-Taussig shunt." In this procedure the left subclavian artery was anastomosed to the pulmonary artery. The operation was first performed at Johns Hopkins on 29th October 1944 and represented the first effective treatment for this condition and it is still used in a modified form today. It was published in JAMA in 1945.  This story would in itself be interesting but what makes it fascinating is the contribution of another member of the team. If you look at the photograph of the operating room you can see there is a man on the far left of the picture standing behind Blalock who is operating. That man was called Vivien Thomas. Nowadays we would call him an African American but in 1940’s Baltimore things were different.Thomas left school at 14 with no college education and started work as a carpenter. After losing his job he obtained a position in Dr Blalock’s laboratory as a janitor. Soon Blalock recognised his exceptional talent with his hands and he became the technician who ran Dr Blalock’s experimental surgical laboratory. When it came to the scientific and the surgical technical aspects of the shunt his own autobiography and detailed research has demonstrated that the primary contribution was from Thomas. Most of the fundamental studies were done by him and Blalock only did one practice procedure in a dog before performing the first surgery on a 15-month-old girl. As the photograph shows Thomas stood behind Blalock during the procedure to provide advice. At a time of racial segregation and discrimination in America, Thomas’s contribution to the development of the shunt procedure remained relatively unknown outside Hopkins. He was ignored by the world’s press and media and the procedure became known as the Blalock-Taussig shunt. He was not even acknowledged for technical contributions in the original paper. However in time, as political and civil rights movements led to change in attitudes towards race, Thomas's exceptional contribution to the development of this pioneering heart surgery was recognised. His portrait now hands in the hallowed corridors of the Johns Hopkins Hospital alongside Dr Alfred Blalock, Sir William Osler, Dr Harvey Cushing and Dr William Halsted – legends of modern clinical medicine. October is Black History Month. You have probably heard of Rosa Parks, Mary Seacole and Claudia Jones but the story of Vivien Thomas is not well known outside of Johns Hopkins. Thomas made a huge contribution to the birth of cardiac surgery and thus plays an important part in the history of medicine. He is a wonderful example of how despite segregation a black man fought against the odds and was key in developing a life-saving operation used to treat thousands of children worldwide. Perhaps it’s time to officially rename the Blalock-Taussig shunt the Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt and give him his rightful place in Black History month.

3 Comments

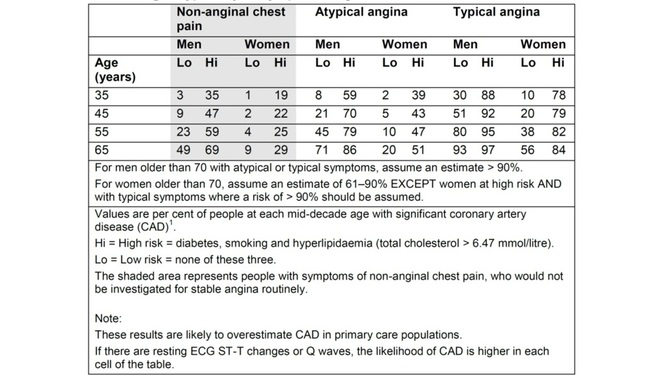

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp. Rembrandt The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp. Rembrandt Medicine, according to Hippocrates, consists of three things – “the disease, the patient and the physician.” But what is disease? It is not simply a state of less than optimum physical health. As Charles Rosenberg says in the introduction to a set of essays on this subject: “In some ways a disease does not exist until we have agreed that it does by perceiving, naming and responding to it." In cardiology there are two diseases which have only been recently “framed." They are Brugada syndrome and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Brugada syndrome was first described in 1992 by the Brugada brothers. They reported the case of a child with recurrent episodes of ventricular fibrillation who had an abnormal pattern of right bundle branch block with ST elevation in the right precordial chest leads. Once this pattern had been described cardiologists looked back to patients they had been managing who were survivors of ventricular fibrillation and people with cardiac defibrillators and found that some of them also had this ECG pattern. Brugada syndrome had existed before this but was simply not recognised by mainstream cardiologists. The syndrome is commonly seen in young men originating from the Far East. In the Thai medical literature, long before the Brugada's description, doctors had described sudden adult death syndrome which was associated with night-time in episodes of ventricular fibrillation which had been called Lai Tai. Most victims were apparently otherwise healthy young men who died unexpectedly during sleep. In some families, similar deaths had occurred for over four generations. It was a local myth that these unexplained deaths were caused by a widow ghost who came to take the mens’ soul at night. It was tradition in some parts of Thailand for men to dress in women’s nightclothes to confuse the ghosts! In other countries similar syndromes were described including Tsob Tsuang in Vietnam and bangungut in the Philippines. Elsewhere the concept of "Voodoo Death" has been well described and may well be related to a cardiac arrhythmia. Another disease recently framed is the Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, also described first in the Far East this time in Japan. It is an unusual form of cardiomyopathy which is usually seen in women and often triggered by a severe emotional disturbance. It is characterised by chest pain and usually patients are usually thought to have an acute coronary syndrome. The first reports of this disease came from Japan possibly because this country is in an earthquake zone and earthquakes provoke severe emotional disturbances. Also Japan has a primary angioplasty service and the Takotsubo diagnosis is usually made when patients are studied in the catheter laboratory. This is because the coronary arteries are unobstructed and there is often a classical appearance of apical ballooning on the LV gram. This syndrome occurs reasonably commonly in clinical practice and until recently was simply not recognised. These two cardiac conditions have only recently been framed as diseases. In the past we would have simply labelled the patients as having idiopathic ventricular fibrillation or an acute coronary syndrome without obstructive coronary disease. I wonder how many other diseases there are waiting to be framed.  Digitalis lanata Digitalis lanata In 1775 William Withering began his clinical investigation into the medicinal properties of the foxglove. Ten years later he published his results. “I soon found” he says, “that the foxglove is a very powerful diuretic of advantage in every species of dropsy except the encysted, and that it has a power over the motion of the heart to a degree yet unobserved in any other medicine, and that this power may be converted to salutary ends.” In the 1890s James Mackenzie advanced clinical knowledge of digitalis. He used the ink polygraph to recorded the venous and arterial pulses simultaneously and showed that the irregular pulse of atrial fibrillation was always associated the absence of the atrial wave in the venous pulse trace. In his clinical studies Mackenzie found that digitalis was particularly effective in patients with heart failure associated with atrial fibrillation. At the same time, chemists were trying to extract and purify the active components in the foxglove leaf. In 1869 crystalline digitoxin was isolated and shown to have similar medicinal properties to digitalis leaf extract. A similar substance was discovered in 1928 and called gitoxin. It was then reported that the leaf of digitalis lanata which grew in the Danube Valley was more than four times as potent as standard digitalis. In 1929 some of the dried leaves were brought to the Wellcome Research Laboratories in Beckenham in Kent where much work had already been done on the purple foxglove to work out methods of extracting and purifying the chemical components. Using the digitalis lanata leaves chemists found a new substance, which formed tiny canoe-shaped crystals, and they named it digoxin. Digoxin became more or less the standard treatment for heart failure associated with atrial fibrillation and also in patients with normal cardiac rhythm. Given by mouth at a dose of 1mg per day or intravenously for more rapid effect it was particularly effective in slowing the heart rate also had diuretic activity relieving the symptoms of congestive heart failure. At a time when the only other therapy was bed rest and mercurial diuretics the effects of digoxin were dramatic and important. Digoxin was introduced into cardiology before clinical trials were the norm and is still part of the current ACC/AHA guidelines. These state that digoxin can be beneficial in patients to decrease hospitalisations for heart failure. What is the evidence behind this recommendation? There are a series of old clinical trials conducted between 1977 and 1993 examining the effects of dioxin in chronic heart failure. Most of them are small and the only large randomised study is the Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) study. In DIG patients with an ejection fraction of 45% or less were randomised to digoxin or placebo in addition to diuretics and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Digoxin did not reduce mortality but did decrease the rate of hospitalization heart failure. Trying to evaluate the place of digoxin is difficult since at the time of the DIG trial β-blockers, spironolactone / eplerenone, ibvabradine or resynchronisation therapy were not recognised treatments for heart failure. So we simply don't know if digoxin is beneficial in patients today, worse still, could it be harmful? In the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial digoxin was associated with higher risk of death and hospitalization for heart failure. The only randomised trial conducted recently showed that in severely ill patients awaiting cardiac transplantation for advanced heart failure digoxin increased risk in death. A post hoc analysis of the DIG trial also showed higher risk of death among women and in a recent study published this year in patients with systolic heart failure showed that digoxin was again associated with a significantly increased mortality. These findings should cause us to reconsider the role of digoxin in the management of patients in sinus rhythm with systolic heart failure. Perhaps after more than 200 years of clinical use it might be time to say farewell to the foxglove as the flower of physic withers.  In 2010 NICE published a guideline on Chest Pain of Recent Onset. This was an important document for GPs and cardiologists. It has been widely cited and has had an effect on how Rapid Access Chest Pain clinics operate. NICE used their usual cost-effectiveness approach to review and then recommend which cardiac investigations were most appropriate in the assessment of patients with chest pain. Some of the recommendations e.g. to not use exercise treadmill testing to assess patients have been largely ignored by many cardiologists but the guidelines have stimulated an increase in the use of non-invasive imaging tests such as CT coronary angiography, myocardial perfusion scanning and stress echocardiography. A recent article in the BMJ “Rational Imaging” series sought to review the investigation of stable chest pain of suspected cardiac origin. Essentially this was a rehash of the 2010 NICE guidelines with focus on the estimation of likelihood of a patient having coronary artery disease and a strong bias to recommended CT and cardiovascular MR imaging (not surprising since all of the authors have specialist interests in this discipline). I think it is time to redress the balance around imaging investigations and critically review the NICE guideline approach. The BMJ article describes the following case: A 45 year old man, who was a non-smoker and did not have diabetes or hyperlipidaemia, presented to his doctor with chest discomfort after exercise. There were no relevant findings on clinical examination and resting electrocardiography (ECG) results were normal. On the basis of age, sex, risk factors, and symptoms, the patient’s pre-test probability of coronary artery disease was 21% and he was referred for calcium scoring. The calcium score was 11 and he proceeded to computed tomography coronary angiography, which identified a 70% stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Adenosine stress perfusion cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed reduced perfusion of the septum within the territory of the left anterior descending coronary artery. He was managed for stable angina on the basis of these findings. I see very many patients with this type of clinical presentation and my approach would not be that recommended by the authors of this article. My clinical impression is that the patient has angina. I would recommend treatment with 75mg aspirin, a beta blocker and to give a GTN spray. I would recommend that the patient has an invasive coronary angiogram. The angiogram is done to define the pattern of coronary artery disease and to decide on the correct approach to further management which may or may not involve revascularisation. The patient starts treatment as soon as the diagnosis of angina is made to improve symptoms and reduce risk of cardiovascular events. So the diagnosis and treatment plan for the patient is completed in a timely manner and with a single test rather than three different tests. NICE and this rational imaging review recommend a different approach. First you estimate the likelihood of coronary artery disease. How? The authors use the table in the NICE guidelines (see below) and say it’s 21%. On that basis they recommend a CT calcium score. I would take issue with this on two counts. First I think the patient’s symptoms are consistent with angina and therefore his predicted risk, according to the NICE guidelines, is much higher at 51%. Second there is evidence that in a younger patient coronary artery disease may occur in the absence of calcification of the coronary arteries. So a zero calcium score does not confidently exclude coronary artery disease in a symptomatic patient. Calcium scoring of the coronary arteries is a relatively quick, cheap and simple test which is entirely non-invasive. CT coronary angiography involves pre-treatment of the patient usually with beta blockers to reduce the heart rate to 60 and pre-assessment of the renal function as intravenous contrast will be administered. The patient then has a CT coronary angiogram and now we see that rather than the predicted 21% chance of having coronary disease the patient does actually have the disease. He then has an adenosine perfusion cardiac magnetic resonance scan (not very widely available, certainly expensive but as all of the authors are experts in CMR scanning not surprising). This demonstrates cardiac ischaemia which is not surprising since there is a flow limiting lesion in a coronary artery and the patient has symptoms of chest pain. After that the patient is managed for stable angina. This management, not discussed in the article, most likely involves an invasive angiogram and consideration of angioplasty to relieve symptoms if not controlled by medical therapy. Whilst the approach described by the authors might be appropriate for an asymptomatic patient it seems a long and complicated route to identify and treat the disease which most cardiologists could have predicted was there from simply taking a proper history. The best predictor of the presence of obstructive coronary artery disease is the presence of symptoms of angina. That’s not to say that patients without angina don’t have coronary artery disease. They do and many patients with significant coronary artery disease do not have classical symptoms of angina. In my view there are two principle questions to address. First, what is the cause of the patient’s symptoms of chest pain? If the answer is coronary artery disease then appropriate investigation needs to be undertaken. If the answer to this is no, then apart from trying to determine the non-cardiac cause of chest pain the other question is could this patient have underlying coronary artery disease? If the risk is high then appropriate preventative measures need to be recommended with regards to lifestyle and other risk factors. It is frustrating that many patients leave a chest pain clinic or accident and emergency department with a diagnosis of “non-cardiac chest pain."  Table from NICE Chest Pain Guidelines. Note the limited ages available for lookup and that "High Risk is defined as diabetes AND smoking AND hyperlipidaemia. This is often misquoted as it has been in the BMJ Rational Imaging Article as diabetes OR smoking OR hyperlipidaemia. Using the table in the NICE guidelines to predict risk of coronary artery disease is risky business itself. First only mid-decade ages are given so most patients fall between the categories of risk. Then with the risk factors you either have none and are low risk or you are a diabetic smoker with a cholesterol of >6.47mmol/l (it’s a strange number because the original study is from the USA and used an LDL cut off of >250mg/dl) and you are high risk. A single risk factor doesn’t count as high risk and so it is impossible from the table to estimate the risk for the majority of patients we see.

You can get around this by going back to the original paper which contains the risk model equations and building your own model to allow the exact age and individual risk factors. NICE didn’t do this in the guideline because it would be too complicated but it is ideally suited to an online version which I will publish soon on my website. Sadly however that doesn’t solve the problem. If you deconstruct the data in the table and go back to the original source you will be surprised and also disappointed. The original data comes from a paper published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in 1993 and reports the experiences of the Duke University Chest Pain Clinic. At Duke they collected sequential data on 1030 patients attending the clinic who were assessed for suspected ischaemic heart disease. 168 patients went on to have a coronary angiogram and from this cohort the risk prediction model was built and this produced the data in the table above. The tiny small sample size and the population on which it is based should make anyone use the NICE table with great caution. One wonders how many 35 year old females with no risk factors and typical angina were really studied by angiography in the 1980's when the data was collected. Certainly to use the numbers as a basis for determining the behaviour of different non-invasive investigation techniques would lead to a very high likelihood of inaccuracy. In the end there is as they say no substitute for experience. The most appropriate way to manage a patient with chest pain is for the assessment to be performed by an experienced cardiologist who can recommend the most appropriate strategy for that individual patient to get to the diagnosis and formulate a treatment plan as quickly and efficiently as possible. References: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chest pain of recent onset: assessment and diagnosis of recent onset chest pain or discomfort of suspected cardiac origin. CG95. 2010. Declan P O’Regan, Stephen P Harden, Stuart A Cook, Investigating stable chest pain of suspected cardiac origin BMJ 2013;347:f3940 Pryor DB, Shaw L, McCants CB et al. (1993) Value of the history and physical in identifying patients at increased risk for coronary artery disease. Annals of Internal Medicine 118(2):81–90. |

Dr Richard BogleThe opinions expressed in this blog are strictly those of the author and should not be construed as the opinion or policy of my employers nor recommendations for your care or anyone else's. Always seek professional guidance instead. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed