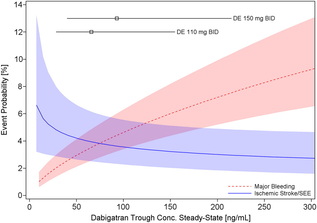

They were a long time coming. We all knew there was a potential for a blockbuster drug one that would make the next billion dollars for its Big Pharma parent. This was going to be “Better than the Beatles”, this was the Stones. There was a false start with Ximelagatran but then with the RELY-AF trial and dabigatran the world changed. Having put up and shut up for 60 years it seemed as though finally warfarin would be consigned to the graveyard of drugs along with old favourites such as guanethidine, reserpine and paraldehyde. The NOACs or new oral anticoagulants were born. They were new, they were oral and they were anticoagulants. However just a minute isn’t there a problem with the NOAC acronym. They won’t always be new will they? They have already been around for 5 years and we are still calling them new. Will they still be new in another 5 years? I propose it is time to stop calling them new and rename then "Non-warfarin oral anticoagulants." We can still keep the catchy NOAC acronym but the new name will reflect what the drugs actually do and that they are different from warfarin. There a subtly in the current acronym which I believe is impeding the widespread adoption of these medicines. The word "new" implies just that. New, therefore we don’t know much about them. New, they are mysterious, perhaps dangerous? The word needs to be dropped. Health economies put up restrictions to impede implementation of new medicines and in the UK the current model of drug development is broken. It was based on the blockbuster and the ability to make a billion dollars from your medicine. It relied on a rapid uptake of the medicine after launch. We now talk about cost-effectiveness of medicines. This is what NICE tests with its unofficial acceptable cost per QALY of £30,0000. What of affordability though? Each health economy has to decide but if you as the patient need the drug and believe it will help me then you don’t really care about the cost per QALY. You probably don’t care about the local health economy or what can and can’t be afforded–you want the drug. Recent headlines about prostate and breast cancer are cases in point. The Cancer Drugs Fund – designed to fund drugs that NICE does not deem cost effective shows that emotion and opinion rules rather than evidence. After all the £30,000 threshold is not scientifically derived it is a matter of opinion and other countries would deem the figure too low after all what price life? There is a subtle trend for the NHS to try and delay and restrict implementation of new medicines for as long as possible. The 2014 NICE guidelines on statins tells us that atorvastatin 20mg is now the preferred statin for primary prevention and 80mg for secondary prevention. This is not because of new evidence – the data has been around for years. The reason is simply that of economics. When atorvastatin was a branded medicine costing £29 per month it wasn’t deemed to be worth it – simvastatin was cheap and therefore more cost effective and more affordable. Now the argument is swept away because atorvastatin is generic and as cheap as simvastatin. We will see the same argument with the NOACs. When they become generic the arguments about effectiveness will all change. The drugs are simple to use as, if not more, effective and don’t require a trip to the anticoagulation clinic. If they were the same price as warfarin there would be no reason not use them. The patent on dabigatran expires in just three and a half years (February 2018) and that is the earliest we will see a generic version appear. At that point use of warfarin for atrial fibrillation and most other indications is likely to cease as the price of the non-warfarin anticoagulants crashes. Will we then stop calling them new oral anticoagulants?

0 Comments

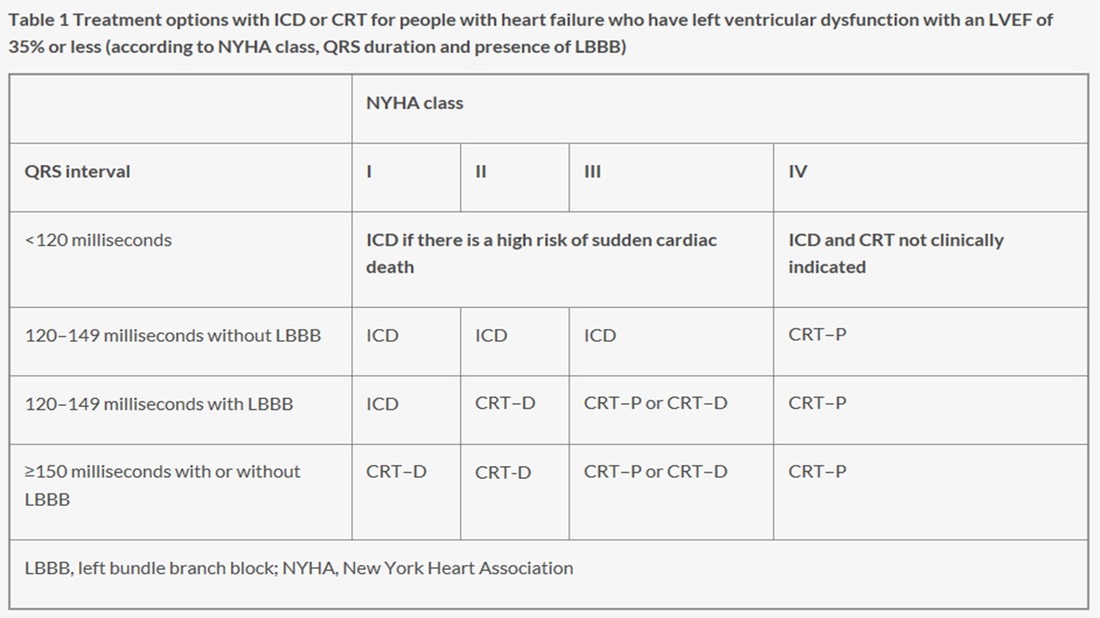

20 years ago today two pivotal papers were published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The BENESTENT and the Stent Restenosis Study compared balloon angioplasty to coronary stenting in people with stable angina. What people remember is that stents were superior to balloons and the rest as they say is history. But the story is more complex than that as the trials show. Stents had been around since the late 1980's and they were effective in treating acute vessel closure due to balloon-induced dissection. This complication was the Achilles heel of interventional cardiology and led patients to emergency bypass grafting when their coronary artery closed off during or shortly after the procedure. Unfortunately Achilles had two heels and the other one was restenosis. Some people thought that stents might be useful to reduce the rate of restenosis but there was a problem. Stents were metal which required use of combinations of aspirin, dipyridamole, heparin and then for three months warfarin. This therapy exposed the patient to a risk of major bleeding and vascular complications prolonging hospital stay. In those days vascular access was via the femoral artery and the sheaths were about 3mm wide. Read today the results of the trials are interesting. Take the BENESTENT trial, the rate of in-hospital events was similar in both groups (6.2% in the balloon vs. 6.9% in the stent group). There was no difference in the incidence of myocardial infarction or in the need for urgent or elective cardiac surgery or second angioplasty during the hospital stay. Stent thrombosis occurred in 3.5% and subacute vessel closure after balloon angioplasty in 2.7%. The incidence of bleeding and vascular complications was 4 times higher at 13.5% after stent implantation than after balloon angioplasty. Hospital stay was 8.5 days after a stent and 3.1 days after a balloon. Now reading this is I am surprised. Stents were not so much better than plain old balloon angioplasty. Acute vessel occlusion was swapped for stent thrombosis and because of the anticoagulation patients had more complications and stayed much longer in hospital. There was no early gain. 20 years on an a coronary stent is a day case procedure done through a tube less than 2mm wide via the wrist and with a complication rate less than 1% and re-stenosis rates almost as low. The requirement for on site surgery is a thing of the past. The speciality of interventional cardiology is now mature. Where will it be in another 20 years?  Have you got a fire extinguisher at home? I haven't but I know they are quite popular. I guess my perception of the risk of a house fire is low enough for me not to have been concerned to have gone out and bought one. But what about a defibrillator? Should cardiac patients consider buying one of these devices. I have never been asked this question until two weeks ago and since then another patient also wanted to discuss the topic. Until the question arose I hadn't really given it much thought. We know that some people with cardiac disease are at high risk of a ventricular arrhythmias and for these people we implant an internal cardiac defibrillator (ICD). But what of the bulk of patients who are not at high enough risk to warrant an ICD but who want to give themselves the best chance of survival should cardiac arrest occur. The Resuscitation Council Advanced Life Support protocol re-enforces that early access to defibrillation is key to survival when ventricular fibrillation occur. So if you have an automatic external defibrillator (AED) at home and someone who knows how to use it, you would by definition get earlier access to this treatment. Provided the treatment did not harm you then the benefit could be as important as the difference between life and death. But is there any evidence that having a AED at home is of benefit? A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine 6 years ago sought to try and answer this question. The investigators recruited 7001 patients with previous anterior wall heart attacks who did not fulfil the criteria for an ICD. The patients were randomly assigned to one of two groups. The first receive standard care and their partners were trained to respond to cardiac arrest by calling 911 and performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). In the second group the partners were trained to use an AED followed by calling 911 and performing CPR. The study outcome was the number of deaths in each group. Patients were studied for 3 years and during that time 450 patients died, 228 (6.5%) in the standard care group and 222 (6.4%) in the defibrillator group. There were no significant differences overall or in any subgroups they examined. Of the 450 deaths, 160 were though to be due to sudden cardiac arrest and of these 117 occurred at home. Of the home deaths 58 were witnessed and the AED used in 32. Of these 32 patients 14 received an appropriate shock and 4 survived to hospital discharge. There was no evidence that the AED gave any inappropriate shocks or harmed people. So why didn't the trial show a difference between the two groups? The rate of cardiac arrest was much lower had the investigators been predicted based on historical studies. This is because the treatment of heart attacks is very good due to primary angioplasty and better drug prevention therapies. The study had a very smaller number of cardiac arrests and was underpowered to detect any effect of the AED. The partners were all trained in CPR and this may also have reduced the effect of the AED. Access to the AED therapy is important and less than half the patients with sudden cardiac arrest at home had a witnessed event, and not all of the witnessed ones had the AED applied. This is perhaps greatest limitation of the AED namely that someone else has to to deliver the treatment. On the positive side however the successful use of the AED in 14 patients and in 4 neighbours resulted in long-term survival for 6 people and this confirms that an AED in the home used by the general public with minimal training is feasible, corrects ventriculal fibrillation and carries no risk of inappropriate shock. So what is my recommendation to patients who ask me "Should I buy a home defibrillator?" I will say that the device is safe and will not harm you. The likelihood of needing to use it is very low but if a cardiac arrest does occur the device will correct the heart rhythm and this may be beneficial and improve the survival of the victim. Whatever they decide the partner should consider attending a basic life support course as defibrillation needs to be combined with CPR. I guess if your the sort of person who has a burglar alarm, smoke alarm and fire extinguisher then your attitude to risk might lead you to purchase an AED, it's a personal decision. The devices cost around £1000 to buy but some would say What price a life!  Guidelines are developed to help clinicians practice evidence based medicine. NICE guidelines are regarded as a pre-eminent source of high quality recommendations which have been evaluated carefully and systematically for cost and clinical effectiveness. NICE published their updated guidelines on implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICD) and cardiac resynchronisation (also known as biventricular) pacemakers (CRT) in June 2014. So which cardiac patients should get an ICD? The first recommendations are clear and well established. If a patient has ventricular fibrillation (VF) or ventricular tachycardia (VT) associated with cardiac arrest or sustained VT (i.e. >30 seconds) with syncope or haemodynamic compromise (excluding people with a treatable cause e.g. acute myocardial infarction) or asymptomatic sustained VT and an ejection fraction of <35% and they are not in NYHA class IV heart failure then they should have an ICD. We all agree with that. Putting it simply survivors of VF/VT cardiac arrest or near cardiac arrest and people with sustained VT and a severely impaired left ventricle should have an ICD. However this is a relatively small group of patients compared to the large group with heart failure who if they do have VT it is usually the non-sustained and asymptomatic type. So what does NICE say with regards to them? Here the guidelines get more difficult. NICE say that an ICDs or CRT with defibrillator (CRT‑D) or CRT without defibrillator (CRT‑P) are recommended for people with heart failure who have an EF of <35% depending on their QRS duration on ECG. If the QRS is normal (ie <120msec) then they recommend an ICD if there is a "high risk" of sudden cardiac death. The rest of the table summaries the other recommendations based on the QRS duration and the NYHA class of heart failure. I want to deal with this first group. The narrow QRS group (<120msec) who have an EF<35%. NICE recommend implanting an ICD if there is a high risk of sudden cardiac death but they don't define high risk. How does the cardiologist identify these high risk patients then? Here we move from evidence to eminence based medicine. The guidelines committee apparently explored approaches to defining high risk people with normal QRS duration. They are not the first to try and do this. Others have an have been unsuccessful. Apparently they concluded that although age and sex were important there were other factors which also played a role. That is not a surprising conclusion that even a non-expert might also reach. They thought that the degree of left ventricular impairment, a history of ischaemic heart disease and how much myocardial scar was present might play a role in increasing risk and possibly factors such as your BNP level might be useful. Again it all valid thoughts but unhelpful in making a decision. I guess there was a lot of discussion but no-one on the committee could agree on how you could tell a high risk patient from a lower risk patient.

Perhaps it time for some pragmatism. You want to implant an ICD in a patient at high risk of sudden cardiac death but you don't have a good way of identifying these patients. The outcome you are trying to prevent is very serious, occurs suddenly and unpredictably. If it happens you don't usually get a second chance to treat it. This means your strategy for prevention will need to be deployed with a very high sensitivity to treat and by definition you will need to accept a lower specificity. Thinking of it a different way if the treatment was a tablet you would put everyone on it because the thing you are trying to prevent is so serious and you only get one chance to do it. That must be the only sensible approach. For people with EF<35% the question is Why shouldn't they have an ICD?

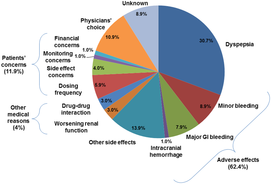

Probability of Major Bleeding Event and Ischemic Stroke/SEE Versus Trough Plasma Concentration of Dabigatran Calculated for 72-year-old male atrial fibrillation patient with prior stroke and diabetes. Lines and boxes at the top of the panel indicate median dabigatran concentrations in the RE-LY trial with 10th and 90th percentiles. Only time will tell as we get a more complete picture of the clinical pharmacology and real world experience of using the NOACs but like all new drugs we should exert a degree of caution and remember that we only know about half of what we need to know when the drug is launched.

|

Dr Richard BogleThe opinions expressed in this blog are strictly those of the author and should not be construed as the opinion or policy of my employers nor recommendations for your care or anyone else's. Always seek professional guidance instead. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed