In the Summer of 2012 David Brailsford presided over Team GB’s incredible haul of cycling medals in the Olympic games. What was the secret of this team’s success? The simple answer was there wasn’t one secret but as Dave Brailsford said it was the aggregation of marginal gains. Performing a coronary angioplasty can take as little as 15 minutes but even with the simplest procedure there are many different choices which the operator needs to make and each of these influences the outcome of the procedure and the risk of complications. Close attention to detail, wise choices and the sum of the marginal gains makes the difference between getting a bronze and achieving gold. Here is an example. The patient is a 75 year old obese man with diabetes and hypertension. He has a stenosis in the mid right coronary artery. The artery is mildly calcified and a somewhat tortuous. Dr Groin is a default femoral operator. With a 6F sheath, a right Judkin’s guide catheter and a hydrophilic guide wire most cases can be done. Groin access takes but a moment and the coronary artery is easily intubated, the wire glides through the vessel with its usual speed and hydrophilic coating. Within moments the lesion is pre-dilated with a balloon. Then comes the stent but there is a problem, the tortuousity and the calcification makes the stent difficult to track through the vessel. The JR4 catheter does not give any support and the stent cannot be manoeuvred into the correct place. A buddy wire is passed but still the stent won’t track to the lesion. Further ballooning is performed in the vessel which results in a small dissection and without the ability to deliver a drug coated stent they try a bare metal stent which is finally deployed with a reasonable result. The procedure takes 75 minutes and there is 300ml contrast used. An angioseal vascular closure device is deployed but does not quite seal the artery completely and the patient develops a haematoma. The patient eventually leaves the hospital 4 days later. His procedure was a success, the vessel was stented but was this as good as it could possibly be. Dr Wrist usually takes the radial approach. A 5Fglideliner sheath and a 6F AL1 guide catheter are used because the vessel is calcified and somewhat tortuous and he thinks that extra support may be needed. The lesion is crossed with a supportive angioplasty wire, the wire is harder to manipulate than the hydrophilic coated wires but once in the distal vessel it gives excellent support and remains very stable. The vessel is tortuous but the AL-1 gives a really good back up support and the lesion is ballooned with a 2.5x12 balloon and then a 3.5x15 drug eluting stent is deployed with a good result. Because the lesion was calcified a further 3.5x12 non-compliant balloon inflation is made to high pressure with a very good angiographic result. The procedure takes 27 minutes and there is 60ml contrast used. A TR band is placed on the wrist with patent haemostasis and the patient is discharged from the hospital 6h later. His procedure was a success, the vessel was stented. Both patients had a successful PCI on paper but Dr Wrist’s procedure was more successful for the patient. The sum of the small parts – access site, catheter choice, wire choice and ability to deliver devices. All of these single decisions feed into the outcome of the procedure for the patient. Alone each one of these things may contribute only a fraction of a percent to a difference in outcome but when they are all put together they can add up and the sum of marginal gains leads to safer and more effective practice. So how do we achieve these marginal gains in practice: Set audacious goals, work with others who share your vision. Focus, Focus, Focus. Collect high quality procedure data, outcomes data and learn from it. Be disciplined to capture every gain.

0 Comments

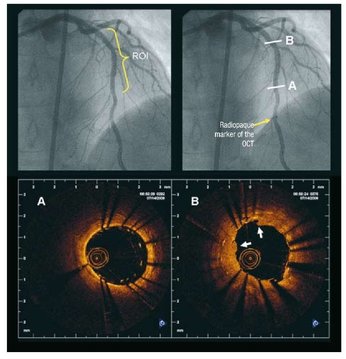

Earlier this week saw the sudden death of the union boss Bob Crow. The headline from the Evening Standard screamed: "Tube Union boss Dies of Heart Attack." He was just 52 years old. Despite advances in treatment of acute heart attacks with primary angioplasty many patients still die suddenly within minutes of the onset of chest pain. The problem with coronary disease is that sometimes the first symptom to alert the patient that something's wrong is when a lethal heart attack strikes. Many patients have not experienced symptoms before that to alter them that there might be a problem. Coronary heart disease does not really have any outward physical signs and so detecting people who may have developed the condition but who have no symptoms is difficult. We recognise various risk factors for heart disease such as age, male sex, high blood pressure, diabetes, cigarette smoking, cholesterol and family history but many people have risk factors and do not develop coronary disease. What would be helpful is an outward physical sign, easily detected, which could alter doctors and patients alike that they might not just be at risk of heart disease but more importantly that they might already have diseased arteries. Over 40 years ago in Dr Sanders Frank reported just such a sign which is today has been forgotten by many doctors and is virtually unknown to patients. In a brief letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine Dr Frank reported his observations of a prominent crease in the ear lobe which was usually present in patients he had seen with coronary artery disease. Initially he reported findings in just 20 patients but since then many studies have been completed confirming his findings. One study of over 1000 unselected patients looked at the presence of a diagonal ear lobe crease and coronary artery disease and found a high degree of correlation independent of age. In this study 112 consecutive patients had coronary angiography and an ear lobe creases was the best predictor of narrowed coronary arteries. Other studies followed which confirmed that ear crease was much more common in patients hospitalized after a heart attack compared to age-matched control subjects with no evidence of cardiac disease. These findings have also been repeated more recently using CT scans to detect coronary artery disease. The presence of an ear lobe crease should alert doctors and patients to the possible presence of coronary heart disease. I don't know anything about Bob Crow's medical history but the picture above a close up of his ear with the ear lobe crease clearly visible. So my advice is clear - look at your ears and if your are under 60 years old and see this change mention it to your doctor.  Angiography of the LAD artery & optical coherence tomography Angiography of the LAD artery & optical coherence tomography The universal approach for deployment of a coronary stents is to use high pressure inflations. This is because high-pressure improves stent expansion and apposition and markedly decreases the incidence of acute and subacute stent thrombosis. In contrast there is no standard protocol for the duration of the high-pressure inflation. Often when a stent is placed the inflation pressure tends to gradually decrease over time suggesting that there is on going slow stent expansion. If the stent further expands with the same inflation pressure then a rapid inflation/deflation sequence may not adequately expand the stent even if the final angiogram looks good. It is possible that sustained inflation until pressure stabilizes would result in more optimal stent deployment. The possibility of incomplete strut apposition may also be heightened if inadequate time is allowed for stent expansion. A recent study has looked at 12 patients having single vessel stent interventions using the new technique of optical coherence tomography. This is an ultrasensitive method that can visualise the apposition of individual stent struts. After pre-dilation the lesions were stented with no angiographic residual stenosis after high-pressure stent balloon inflation of relatively short duration (“rapid” inflation) with an average inflation time of 28±17 sec. Following an OCT measurement prolonged inflation was performed. The inflation time was chosen such that the pressure in the inflation device was completely stable for at least 30 seconds. In order to achieve this it required much longer periods of inflation for 206 ± 115 sec. The patients appeared to be stable during this long inflation but what is interesting is that the minimal stent diameter and minimal stent area both increased after prolonged inflation compared with rapid inflation. Stent diameter increased by 9% from 2.75 ± 0.44 to 3.0 ± 0.5 (P < 0.0001) and stent area by 18% from 6.63 ± 1.85 to 7.83 ± 2.45. Not only this but stent strut mal-apposition was halved. This is a small study but important as it makes us think once again that the coronary angiographic results is a relatively crude guide to the apposition of the struts and the overall deployment of a stent. We should consider using both high pressure and longer inflations.  Are you confused about what to eat? It can't be because of lack of information. Search Google today for the word "diet" and it will give you over 136 million hits with over 4 million in the News section alone. Most stories are here today and gone tomorrow and who bothers to look at the evidence behind the headline. Take the one on today's front pages: "Eating too much meat and eggs is as deadly as smoking." Really? Taken at face value this should be a public health emergency. Warnings on plates used to serve the full English breakfast ought to be introduced, we might even call for an ingestion charge on meat and eggs! But probably what will happen is that we will forget the headline by tomorrow certain in the knowledge there will always be another story this time telling us that too much fat or sugar or carbohydrate or this or that is bad. Confused about what the best diet is? Of course you are who wouldn't be? With so much conflicting information it is difficult to know what to believe. So what of the study reported today? Should we worry about meat and eggs? Are they really as dangerous as smoking?The story comes from a paper published in Cell Metabolism. This is a "good journal" with a very high impact factor. In other words you would be proud to have your research published there. The study followed 6.381 adults, 50 years old and over for 18 years. So far so good, a large study sample with long follow up. They found that people with diabetes were more likely to die from diabetes if they had a high protein intake. They assessed protein intake using a diary card for 24h at the start of the study ie about 20 years ago. Are you still eating the same diet as you were 20 years ago? I thought so but anyway not to worry the authors assumed that the people's diet remained unchanged for 20 years. When the results were analysed there were no differences in death rates overall, cancer or cardiovascular deaths. Now this ins interesting because the group eating a lot of protein had a much higher proportion of diabetic patients and you would have though that the cardiovascular death rate would be higher in that group. Then if you look at the data more carefully you notice that the death rate from diabetes in the study is very low indeed (about 1in 100). Most people died of cancer or cardiovascular disease as expected The proportion of diabetics in the high protein group was 17% whereas it was only 2.6% in the low protein group. Presumably this reflects the advice given previously by diabetes specialists to recommend high protein diets to diabetics as it was thought that the blood sugar levels were easier to control. So this group has far higher numbers of diabetics and if you look at the proportion of diabetics in each group which died of diabetes then it is 7.7 for the low, 8.7 for the intermediate and 11.8 for the high protein groups. Not so different and because the numbers are small the accuracy is low. Not withstanding this the investigators analysed the data some more and managed to find an association between age, protein consumption and cancer mortality. If you are 50–65 years you get benefit from a low protein intake but once you are over 65 then it is harmful. Is this biologically plausible? So that's just one headline on one day. But there is a message there: Meat and eggs are as deadly as smoking. This is confusion at best and harmful at worst as this study really doesn't support that conclusion. In the end it is likely that the public, seeing so many stories which apparently contradict each other, will decide that no-one really knows what the best diet is and carry on eating their usual food.  When doctors are asked to classify atrial fibrillation (AF) they usually start by describing it as paroxysmal (coming and going) or persistent. When they are asked about the causes of AF they will usually list high blood pressure, ischaemic and valvular heart disease, alcohol and over active thyroid. These things are definitely associated with AF but what triggers episodes. Another way of classifying AF is Sympathetic or adrenergic AF and vagal AF. The initiator of the AF episodes can often be overlooked in the consultation but is very important particularly as vagal AF will gets worse when treated with beta blockers. The vagus nerve wanders from the brainstem throughout the chest and abdomen innervating the heart, lungs and intestines. It is part of the autonomic nervous system and its cardiac action is to slow the heart. For some patients increased vagal activity is associated with the initiation of atrial fibrillation. So called vagal AF is enigmatic but should be more recognised. This is important because it needs to be managed differently from other more common types of atrial fibrillation. When to suspect vagal AF: If the arrhythmia occurs at rest, after meals or during sleep then it is more likely to be vagal stimulated. Commonly this type of AF stops in the morning or during periods of exercise and can be precipitated by cough, nausea, after eating, swallowing and ingestion of cold foods and drinks. Vagal AF is more frequently seen in younger patients (30-50 years old), typically men and usually the heart is structurally normal on echocardiography. If the patient participates in endurance sports such as cycling, marathon running or cross country skiing then AF is also more common. ECG recordings often show a combination of atrial flutter alternating with atrial fibrillation. When a 24h ECG monitor is performed sinus bradycardia usually occurs before the onset of the AF. The ventricular rate during the AF is generally not fast. It is possible to measure the activity of the autonomic nervous system but it is difficult. One way is to assess heart rate variability which can assess the balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic or vagal tone. Vagal stimulation shortens atrial effective refractory period and augments the ability of a single atrial premature beats to induce AF. How should vagal AF be managed? Anticoagulation as per the underlying stroke risk predicted by CHAD2VASC score should be considered. With respect to reducing vagal AF episodes there are only anecdotal data about the best way to manage this. Drugs which block the sympathetic nervous system commonly used in the management of AF such as beta blockers and digoxin should be avoided. Alternative drugs such as those which reduce vagal tone should theoretically be effective. These drugs include flecainide, quinidine, and disopyramide. The pulmonary veins are a well-recognised source of AF in many patients and ablation can be effective in reducing paroxysmal AF. In contrast there are no specific studies reporting the success of ablation in vagal AF. One recent development is the awareness of increased activity of the If channels which raises the possibility that blockade of these channels with ivabradine might have an anti-arrhythmic in vagal AF patients. This is still an area for research and further information will be needed before this can be used routinely in the clinic.  Yesterday the 2014 AHA/ACC Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease were released. Last published as a full guideline in 2006 and updated in 2008 the new guideline occupies 235 pages and is supported by 939 references. The guideline development group have sifted, weighted and considered all the evidence and come up with 226 recommendations for you and me to follow. In this type of guideline the strength of evidence supporting each recommendation is graded as A, B or C. A recommendation supported by evidence graded as an A is derived from multiple randomised trials or meta-analyses, Evidence graded as B comes from a single randomised trial or more usually non-randomised trials and evidence graded as C is expert opinion. In this new guideline just 7 out of the 226 recommendations are supported by A grade evidence and of the remainder, over half (112 to be precise) are the product of just expert opinion. The 7 recommendations supported by top class evidence a straightforward enough. For example they recommend replacing the aortic valve in people with an indication for aortic valve replacement who have acceptable surgical risk, seems logical. They recommend treating patients with heart failure who also have mitral regurgitation with guideline directed medical therapy and using resynchronisation therapy for those who meet the indications for this treatment; again this seems logical and derives from clinical trials of heart failure rather than valve disease. They recommend giving warfarin to patients with mechanical prosthetic valves; Is there anyone who wouldn't do that? They also recommend giving aspirin in addition to warfarin to patients with mechanical valve prosthesis; I don't think that practice is very widespread even though it comes from a trial published in 1993. It seems cardiologist ignore some evidence when it suits them. They also recommend treating symptomatic severe mitral stenosis with balloon valvuloplasty provided there are no contraindications and tell us not to give statins to reduce progression of aortic stenosis - they don't work. Actually this latter recommendation is interesting since there were a large number of retrospective and case-controlled studies which indicated that statins reduced progression of aortic stenosis. When the blinded clinical trials were done however these drugs were without effect. What of the recommendations based on level B and C evidence. As the guideline document states just because the level of evidence is C does not necessarily mean that the evidence is weak but they would say that wouldn't they. In fairness some clinical questions are not suited to randomised clinical trials so I don't think there will ever be a trial to investigate whether taking blood cultures before antibiotics are given for endocarditis is appropriate or not. Currently the biggest challenge and difficult decision is when to refer asymptomatic patients for valve replacement or repair. The guideline helps us here recommending various cut-offs of left ventricular size and function but what of the evidence supporting these recommendations. Lets take one as an example: On page 56 the guideline says: Aortic valve replacement is reasonable for asymptomatic patients with severe aortic regurgitation and normal LV function (EF>50%) but with severe LV dilatation (LVESD >50mm or 25mm/m2). [Class IIb, Level B]. This recommendation is supported with evidence from three studies. The first (reference 226, Van Rossem et al), is an imaging study describing a comparison of MRI and angiography for the assessment of LV ejection fraction and it doesn't seem to have too much to do with when to operate for aortic regurgitation. The other two studies (Bonow et al, reference 243 and Gaasch et al, reference 244) are actually about aortic regurgitation which is a good start. The Bonow paper looked at 61 patients all with dilated ventricles who had an aortic valve replacement. They found that after the operation the diastolic dimensions decreased. In this study a third of the patients could not complete an exercise test to 8METS of workload so they were anything but asymptomatic and more importantly everyone got an operation so the study doesn't tell you when to operate. The other study was an extensive treatise on 31 patients with severe aortic regurgitation. In this study 23 had NYHA class 2 or 3 symptoms - so again not asymptomatic. The authors concluded that LV enlargement could be detected by echocardiography. Again not a study of when to operate. So these papers don't really support the guideline recommendation and we need to be cautious because there is a tendency for weak recommendations based on little evidence to gain strength when they enter a guideline. Guidelines are disseminated at meetings and internet presentations. Some people will read the executive summary, some will skim though the guideline document. Only a very few will read the guideline and then go back to the original studies that support the recommendations to evaluate them in detail - we assume the guidelines development group will have done due diligence. Although we chant the mantra of evidence based medicine in many cases we are still practicing eminence based medicine. |

Dr Richard BogleThe opinions expressed in this blog are strictly those of the author and should not be construed as the opinion or policy of my employers nor recommendations for your care or anyone else's. Always seek professional guidance instead. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed