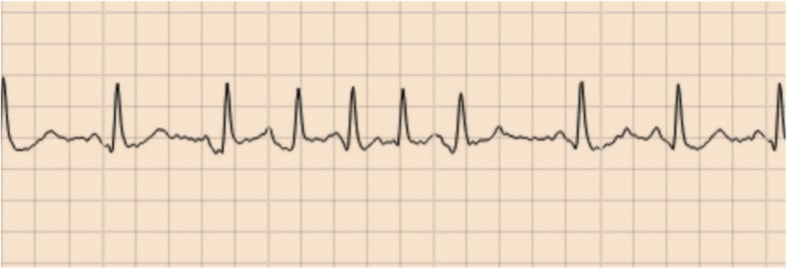

If a primary care physician receives a continuous ECG monitor report indicating the presence of short runs of an irregular, non-P wave associated, atrial rhythm lasting <30 s what should they do? What should the reporting cardiologist call this rhythm? What does it mean for the patient now and into the future? As someone who reports ECG monitors and gives advice to primary care physicians these questions come up a lot. I usually go with the description of the short runs of an irregular ......but just this weekend I came across a new term whilst listening to the This Week in Cardiology podcast - micro atrial fibrillation (micro-AF). This podcast is hosted by the cardiologist Dr John Mandrola and I would say this should be required weekly listening for any practicing cardiologist. It is one of the most well thought through and interesting cardiology podcasts around. John is a "conservative cardiologist" and takes a careful evidence based approach. He's practicing doctor, seeing patients and grapples with the common and difficult clinical scenarios we all come across on a daily basis in our practice. Anyway, back to micro-AF, my new learning of the week. Of course this is not a new phenomenon but something which we all recognize when we are reporting continuous ECG monitors. Diagnosis of AF should be easy. You get an ECG and there 's an irregular rhythm, no P waves and well that is AF but what about when your looking at continuous ECG monitors and there are short runs of irregular rhythm without P waves - how long does this irregular rhythm need to last for it to be called AF. Fortunately there is a definition that it should last more than 30 s for us to consider it AF. Of course this is arbitrary definition - who said 30 s was the right length of time and not 15 or 60 s. Like most of these definitions they emerge from guidelines and a good measure of eminence based medicine. So what about when these irregular, non P-wave containing rhythms which last less than 30 s? What do we call them? I've seen people write things like short runs of atrial ectopics, although an ectopic should be associated with a P wave. I've see short runs of an irregular atrial associated rhythm or short runs of pulmonary vein rhythm. Alternatively we could call them atrial junk (as per John Mandrola) or we perhaps just micro-AF. At face value micro-AF seems like quite an attractive term - after all everyone knows AF and I suppose these are little AF episodes. The term could be useful if they predict AF in the future or are AF but just not 30 s worth of AF then that might be reasonable. What matters is the significance and more importantly what we advise colleagues in primary care and outside of cardiology to do with these patients. I'm concerned if we label them as micro-AF then primary care physicians will be immediately reach for anti-coagulation. If we call them "atrial junk" or other names then we will need to qualify that with some advice, otherwise we are likely to generate significant confusion. So what do these short runs of irregular, non-P wave containing atrial rhythm actually mean. The Swedish group who have coined the term micro-AF have published several studies in this area. They define micro-AF as an irregular tachycardia of sudden onset with episodes of ≥5 consecutive supra-ventricular beats without P waves lasting less than 30 s. In STROKESTOP2 they reported on 3,763 of older people (75 years) screened with intermittent ECG recordings for 30 s 4 times day for 2 weeks. 121 (6%) had micro-AF and of these who then underwent a 2-week period of continuous ECG monitoring AF was detected in 26 (13%). In a control group of 250 people without micro-AF then the continuous monitoring detected 7 cases of AF (3%) So we can conclude that having this micro-AF is associated with a four-fold increase in the risk of detection of AF. In another of their studies called STROKESTOP, 50% of participants diagnosed with micro-AF (this time defined as: abrupt onset, >4 supra-ventricular beats, irregular, no P waves) when followed for 2.4 years ended up with AF detected on monitoring compared with just 10% of patients who did not have micro-AF at baseline. So it certainly looks like having these short runs on the continuous ECG is associated with a higher risk of having longer runs (>30 s) in the future. So what to do if we find AF on continuous monitoring. Is there a case for anti-coagulation of these short episodes of AF? Is it time to anti-coagulate micro-AF. Does any of this reduce the risk of stroke or is it all just atrial junk! We have data on this because the LOOP study reported that in individuals with stroke risk factors an implantable loop recorder (ILR) screening whilst resulting in a 3-times increase in AF detection and anti-coagulation there was no significant reduction in the risk of stroke or systemic arterial embolism. These tell us that screening for AF and then treating it with anti-coagulation is not a worthwhile use of resources and does not benefit the patient. So for now I'm going to avoid the term micro-AF for fear it might cause people to confuse these with AF. Are they atrial junk - well I suppose they could be but I'd feel uncomfortable writing that on a report so for the moment I think the best way is to give a narrative verdict and reassure.

0 Comments

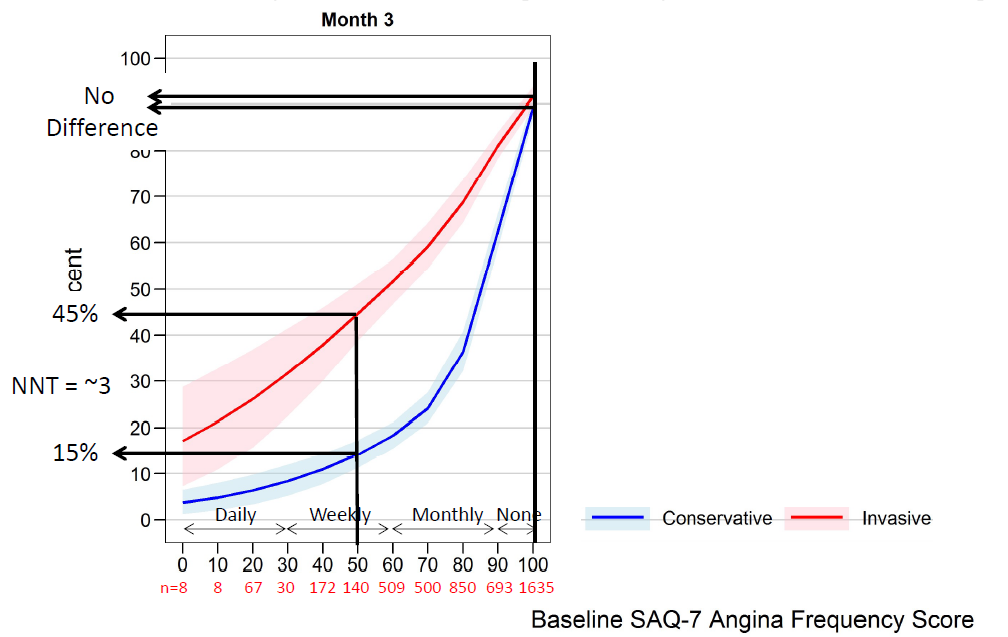

The ISCHAEMIA trial examined two approaches for the management of stable angina/ischaemic heart disease. The results have been much anticipated ever since the COURAGE trial shook the interventional community by showing that stenting in stable coronary artery disease was not associated with a reduction in cardiovascular events. The paper with the results of the ISCHAEMIA trial the results is not due out until next year but the results were been presented last weekend at the American Heart Association meeting in Philadelphia. Patients presenting with stable angina were assessed initially with a stress test. 75% had stress imaging test and 25% an exercise ECG. Subjects had to have evidence of ischaemia to be included in the trial (54% severe, 33% moderate and 12% mild ischaemia). Subjects also had a CT coronary angiogram to exclude left main stem disease (>50%) and to exclude people without CAD (<50% stenosis with stress imaging and <70% stenosis with exercise ECG). The results of the CT scan were not available to the clinicians – all they knew was the patient didn’t have left main disease and did have >50% in at least 1 major epicardial vessel. Patients were excluded if they had recent acute coronary syndrome, were highly symptomatic with angina, if eGFR <30ml/min or if the LVEF<35%. Subjects were randomised to either an invasive approach with cardiac catheterisation and revascularisation or a conservative approach with medical therapy. 5,179 patients were randomised (2,591 to conservative and 2,588 to invasive approach). Follow up was 4 years. The primary outcome was going to be CV Death and MI but this was changed in 2018 to a broader composite endpoint of CV death, MI, hospitalisation or unstable angina, heart failure or resuscitated cardiac arrest. Presumably this was because the event rate was smaller than expected. The prmary endpoint was not significant different between the two approaches. There was a significant increase in procedural MI (HR 2.98) and a significant decrease (HR 0.67) in non-procedural MI and admission to hospital with unstable angina (HR 0.5) in the invasive arm although the rates of all these events was low. The trial says that if you manage patients with angina, moderate-severe ischaemia and CT scan documented CAD by a conservative strategy you will not reduce the overall rate of CV events. If you choose a conservative strategy 9% of patients at 6 months and 28% at 4 years will end up having an angiogram, presumably due to symptoms, and 7% and 23% at 6 months and 4 years respectively will have revascularisation. If you choose an invasive approach about 2% of patients will have a procedural associated MI but there will be a reduced risk of non-procedural MI over the 4 years from about 10 to 8%. The risk of admission to hospital is reduced from from 2 to 1%. By any measure these are small effects. So was there a big difference in quality of life. The study used the Seattle Angina Questionnaire to assess the response to treatment. The probability of being angina free at 3 months was 45% if the subject had the invasive approach and had weekly symptoms of angina. For the conservative approach the chance of being angina free was just 15%. Care is needed in extrapolating these results beyond 3-months because the benefits of PCI usually reduce over time. Also we know ORBITA study there is a significant placebo effect of PCI procedures. If patients did not have angina there was no difference between the conservative and the invasice strategy. The Bottom Line for Patients: If you have stable angina, a positive stress test and no significant disease of the left main an angiogram/revascularisation will not your risk of having a major cardiovascular event in the next 4 years. If you opt for an invasive approach there is a small risk you will have a procedural related MI. This risk is balanced by a lower chance of being admitted with unstable angina or having a spontaneous MI. If you have moderate angina, then you have a higher likelihood of being free of angina if you have an invasive strategy versus a conservative strategy at 3 months, although the benefit may reduce over time. If you don't have angina there isn’t any tangible benefit of the invasive strategy and you should an invasive approach for the moment. The figure below is useful as it relates your baseline angina severity (x-axis) against the liklihood of being free of angina with the 2 approaches. If you opt for a conservative approach there's a 1:3 chance you will end up with an angiogram in the 4 years and a 1:4 chance of having revascularisation due to symptom progression.

There will be a lot more discussion about the ISCHAEMIA trial as cardiologists and patients digest the results. The most important advice is don't rush to angiography and stenting for stable angina. Take time to consider the options. ischemia_main_11.15.19_final.pdf Currently there is much debate whether angioplasty and stenting (known as PCI) alters prognosis in stable coronary artery disease. The COURAGE trial published nearly 10 years ago indicated that optimal medical therapy was the key to modifying prognosis and that scaffolding narrowed coronary arteries with stents was not very important. Since then there have been growing calls to reign in the exuberant practice of the “Balloonatics” and the “Stentaholics” with criticism of interventional cardiologists’ for performing “Too much angioplasty” guided by the wonderfully named “oculostenotic reflex”.

Despite COURAGE a large body of evidence has also been accumulated showing that coronary ischaemia, whether silent or associated with angina, is associated with a worse outcome for patients and there is data from COURAGE showing that PCI is more effective at relieving ischaemic than optimal medical therapy. Current guidelines are very focused on detection of ischaemia and using that to guide PCI. It is interesting that PCI has been around for almost 40 years, millions of procedures have been performed, and yet there is still a huge debate on whether the treatment is more effective than tablets for the treatment of stable coronary artery disease. A recent paper provides an interesting perspective and was an analysis of the REACH registry. REACH is a large multinational registry that collected data on 68,000 patients from December 2003 to June 2004. About 30,000 of them had a history of coronary artery disease and the study compared the outcomes of those patients with and without prior coronary revascularization. They found that those patients with a history of PCI had much better outcomes than those with no history of revascularization. These data should reassure patients who have had revascularization, but also lead us to revisit whether optimal medical therapy is as optimal as its proponents would lead us to believe. Of course in a registry study it is not possible to exclude bias completely even with complex statistical approaches and propensity matching. For example, some patients will have undergone angiography and been found to have minor disease, others might have had severe and extensive disease not amenable to any form of revascularization. However the study does provide reassurance that PCI may improve prognosis as well as be effective for the treatment of angina. So how should we manage patients with angina in 2016. Should we offer optimal medical therapy first and then only offer angiography to those with continuing symptoms? Should we try to demonstrate ischaemia and if we find it proceed to angiography? Should we proceed straight to angiography and then consider the anatomical appearances and make a decision based on the lesion severity or with a pressure wire. If ischaemia is demonstrated should the extent play a role in the decision-making process for both angiography and revascularization? From the simple times of the oculostenotic reflex things have become a lot more complex and uncertain. NICE guidelines for assessment of patients with chest pain reduced the threshold to recommend invasive coronary angiography as the first line test but does early angiography risk decisions being made on the basis of the anatomy alone. Once the information about the coronary anatomy is known it cannot be unknown and may have a significant influence on the decision making process. Take an patient with a single episode of chest pain, who has a borderline exercise ECG and then turns out to have a 90% mid right coronary artery stenosis. Most people knowing this piece of information would be keen for treatment to relieve the stenosis rather than just receive medicines. Psychologically having an effective treatment for your narrowed coronary artery might be expected to have both a physical but also an important psychological benefit, although this has never been investigated. Results from the ISCHEMIA trial may help us to better understand this question but in the meantime patients present to cardiologists and decisions have to be made in an area of uncertainty. Also we can’t also pin all our hopes on the results of the ISCHAEMIA trial. What we can be sure of is the debate between PCI and OMT will continue for a long time to come. Direct acting oral anticoagulants (DOAC) have revolutionised the management of atrial fibrillation (AF). There are four medicines licenced to reduce the risk of stroke and thromboembolism in patients with non-valvular AF – Apixaban, Dabigatran, Edoxaban and Rivaroxaban.

Each DOAC has been compared to Warfarin in large randomised clinical trials and all have shown either non-inferiority or in some cases slight superiority to Warfarin. It is difficult to compare the drugs head-to-head because the trials all had slightly different design however recently there has been some uncertainty about the Rivaroxaban ROCKET-AF trial. Rivaroxaban has become one of the most popular DOACs because of its once daily dose regimen and is very well-tolerated. To date it has been my DOAC of choice. The ROCKET-AF trial was criticised after publication for potentially being biased in favour of Rivaroxaban. This was because the time in the therapeutic range for the Warfarin patients was just 55%. In other words, the INR of patients on Warfarin was between 2 and 3 just over half the time. The optimum time in the therapeutic range for a patient on warfarin should be >70%. More recently the trial has come under fire because the INR monitoring was performed using a point-of-care device that has been subsequently recalled by the FDA. The device produced inaccurately low INR results in some patients. This had the potential to produce falsely low INR readings. This meant that the dose of Warfarin prescribed would have been increased thus exposing patients to potentially higher bleeding tendency. The faulty INR machine used in the trial led to potential overdosing of warfarin which could have led to higher bleeding in the warfarin group. However, in the trial the annual risk of major bleeding was 3.6% with Rivaroxaban versus 3.4% with Warfarin. If the patients on Warfarin had a higher bleeding tendency because nearly 40% were being over-treated this could have increased the major bleeding rate in the Warfarin group and difference in major bleeding caused by Rivaroxaban The trial authors have now responded to this by publishing a Research letter in the New England Journal of Medicine. They reporting that 37% of patients treated with Warfarin had a condition that could have been affected by the faulty INR device. They performed an analysis of these patients and reported that the main results of the trial were unaffected. Sceptics have responded in an article in the British Medical Journal calling for release of the patient-level data as they don’t trust the investigators analysis. So far the company have not indicated that they will release the data. Should we continue to prescribe Rivaroxaban for new patients and should patients currently on the drug be confident to continue taking it? In the post-marketing Xantus study with Rivaroxaban the annual rate of major bleeding was 2.1%, stroke 0.7%, and death 1.9% which were either equivalent to or less than those reported in ROCKET-AF. So in real life clinical practice the drug appears to perform in a manner similar to that achieved in the ROCKET-AF trial. Although that is not surprising since it was the Warfarin comparator group where the problem lies and therefore interpreting difference between Warfarin and Rivaroxaban. Up to this point the main reasons to choose Rivaroxaban are the simple once-daily dosing and good tolerability. Recently Edoxaban has been launched in the UK and this is also once daily. In the clinical trial of Edoxaban versus Warfarin time in the therapeutic range was 68.4%, which is good and a different point of care INR monitoring machine was used. The average CHADS2 score in the trial was 2.8 and Edoxaban was non-inferior to Warfarin for stroke prevention with a trend towards a lower annualised risk of major bleeding of 2.75% versus 3.43% with Warfarin. Certainly Edoxaban looks an attractive candidate to become my DOAC of choice going forward. When a patient complains of palpitations and a diagnosis of atrial or ventricular ectopic beats is made the cardiologist's recommendation usually starts with some lifestyle advice such as avoiding caffeine. Since these tea and coffee are often an integral part of our daily routine you might ask; What is the evidence for this recommendation and is it effective? Limiting caffeine consumption forms part of common medical advice. In one study of 697 medical specialists surveyed about caffeine >75% recommended caffeine reduction for patients with anxiety, arrhythmias, oesophagitis/hiatus hernia insomnia, palpitations, and tachycardia.

A recent poster at the Heart Rhythm Society meeting looked at the database of the Cardiovascular Health Study. This study began in 1989 and has followed more than 5000 patients aged 65 years or over. The researchers measured the number of atrial and ventricular ectopic beats in 1414 individuals randomly assigned to have 24h tapes fitted. Then they looked at the results of self-reported food frequency questionnaires and determined whether there was any association between the amount of caffeine consumption and the number of ectopic beats. In a nutshell, there was none and therefore in an asymptomatic group of older patients ectopic frequency is not linked to caffeine intake. However these were asymptomatic people and perhaps in folk with palpitations caffeine withdrawal might just improve symptoms. If you search the medical literature for "caffeine" and "palpitations" you will find only a single study which has looked at this question. The researchers entered 13 patients in a randomised, double blind, 6 week intervention trial of dietary caffeine restriction, caffeinated coffee, and decaffeinated coffee measuring caffeine levels in the blood, a visual analogue score of palpitations and 24 hour ventricular premature beat frequency. Their interventions significantly reduced serum caffeine concentrations. The palpitation scores showed a small, but significant correlation with ventricular premature beat frequencies (r = 0.34) but there were no significant changes in palpitation scores or ventricular ectopic beat frequencies during the intervention weeks and no correlations between these variables and serum caffeine concentrations. The authors concluded that caffeine restriction has no role in the management of patients referred with symptomatic idiopathic ventricular premature beats. So it seems at least as far as ventricular ectopic beats are concerned our advice to reduce caffeine consumption with the aim of improving symptoms is no founded on any evidence. For my own patients I usually say that if they want to give up tea or coffee for 2 weeks and review their symptoms that is fine. If the intervention subjectively makes a substantial improvement to how they feel then continue off the caffeine, otherwise go back to your normal regime. It is interesting that such commonly given advice is founded on such a weak evidence base.  On March 13th the Food and Drug Administration finally approved the WATCHMAN device for prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) in the USA. The WATCHMAN is a percutaneous implantable device designed to occlude the left atrial appendage (LAA). It's been a long journey for this device, now owned by Boston Scientific and six years have passed since the publication of the first clinical trial, PROTECT-AF. In AF 90% of cardiac thrombi are thought to originate in the LAA. A strategy to occlude or remove the LAA is an attractive target to reduce stroke risk and avoid the need for lifelong anticoagulation. Already some cardiac surgeons routinely remove the LAA at the time of cardiac surgery. There is a clinical trial, which will report in 2016, testing the hypothesis that this additional surgical procedure will reduce the risk of stroke. Even if this trial is positive however it will only be relevant to patients undergoing cardiac surgery for other reasons and not open to the vast majority of patients with AF. The PROTECT-AF trial showed the device was non-inferior to warfarin for stroke prevention but there was a high rate of serious procedure related complications. Interestingly when the data was analysed looking at earlier versus later implants the complication rates decreased markedly as operator experience increased. This was confirmed in a later follow-up registry study and further date came from another clinical trial called PREVAIL. If you want to read all of the clinical trial data in detail then the summary on the FDA website is excellent. The clinical trials with the LAA device are very small in comparison to modern pharmaceutical trials. For the NOACs in AF we have four mega-trials and a meta-analysis with 102,000 patients worth of date. Compare this to the PROTECT-AF trial with its mere 707 patients. It is therefore not surprising that the confidence intervals in this device trial are very wide. Interestingly the major benefit in the PROTECT-AF trial was the reduction in the risk of intracranial bleeding. Since this safety endpoint is significantly reduced in patients taking NOACs it would be more appropriate to be considering comparing the LAA occlusion devices with NOACs rather than Warfarin. Now the device has been approved by the FDA we will see a surge in the rate of implants in USA. In Europe already the implant rate is very high in Germany a phenomenon very commonly seen in this country when it comes to the treatment of patients with devices and interventional procedures in cardiology. In the UK some centres such as the Royal Brompton Hospital have implanted over 100 devices. Interestingly NHS England's specialist commissioning have recently selected two different tertiary centre units to perform this procedure in London. Perhaps they didn't consider that the association with operator experience and procedural complication rates was important. Personally I think that the LAA occlusion device will end up as a niche procedure which has a role for those patients with a high CHADSVASC score who are unable to take oral anticoagulants. It is vital going forward that more research takes place with the WATCHMAN and other LAA occlusion devices to determined whether their potential promise will be delivered. At this point we are right to ask Quis custodiet ipsos custodies?  In people admitted to the hospital with cardiac chest pain a subgroup is recognized on the basis of a characteristic ECG change that predicts a high risk of impending extensive anterior myocardial infarction. The ECG has a highly characteristic ST-T segment change in the chest leads and at angiography patients usually have a critical stenosis in the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. In the original paper published in 1982 in the American Journal of Cardiology they found 26 patients out of 145 consecutive admission had this typical pattern. The description was of abnormal ST-T segments in leads V2 and V3 consisting of an isoelectric or minimally elevated (1 mm) take-off of the ST segment from the QRS complex, a concave or straight ST segment passing into a negative T wave at an angle of 60 to 90 degrees, and a symmetrically inverted T wave. Twenty-five of the 26 patients also had a typical pattern in lead V1: an isoelectric or minimally elevated (1 mm) take-off of the ST segment and a concave or straight ST segment passing into the first part of the T wave at an angle of approximately 135 degrees, followed by T wave inversion. In addition, 22 had an ST-T segment pattern in lead Vl, and sometimes V2 and V3, consisting of a take-off of the ST segment from the QRS complex below the isoelectric line and a convex ST segment passing into a negative T wave at an angle of about 120 degrees with a deep symmetrically inverted T wave. As with many things a picture says a thousand words and the figure illustrated above shows the two patterns. The original paper published in 1982 shows the natural history of this condition if managed conservatively with beta blockers and GTN. They had 145 patients consecutively admitted with chest pain of which 18% had the characteristic ECG pattern and 75% of them who were not operated on developed an extensive anterior wall infarction within a few weeks after admission. The authors recommended that patients with this ECG pattern should have urgent coronary angiography and revascularization. Cardiologists now refer to this ECG pattern as a Wellens ECG or Wellens syndrome. In a patient with symptoms of chest pain it should prompt the patient to be admitted to hospital irrespective of the troponin level and urgent coronary angiography arranged. This is certainly a situation where coronary revascularisation will reduce the risk of myocardial infarction.  Do you remember the children's song "I know an old lady who swallowed a fly?" She swallowed a spider to catch the fly, then a bird to catch the spider, she swallowed a cat to catch the bird etc. Eventually she swallowed a horse - and as the song goes "She dead of course!" This song reminded me of a recent patient. A middle aged man with no medical problems, normal blood pressure and a cholesterol of 5.4. He happened to have the "good fortune" of being sent for a routine executive medical. The ECG was abnormal showing left axis deviation and a Q wave in lead V2. The ECG report suggested cardiology referral and recommended an echocardiogram. The echocardiogram showed possible septal hypokinesia with good LV function and normal valves. The echo led to a CT coronary angiogram which showed a normal left coronary and a 50% stenosis in the mid right coronary artery. The CT led to an exercise ECG which showed 1mm ST depression infero-laterally at 6 minutes of exercise. The exercise ECG led to an invasive angiogram which showed a moderate mid right coronary stenosis. The angiogram led to FFR measurement of the lesion with a FFR at maximum hyperaemia of 0.74. The FFR led to a coronary stent being implanted and the prescription of dual antiplatelet therapy, ACE inhibitors, intensive statins and beta blockers. The patient was asymptomatic physically but anxious. How would he know if coronary disease were to occur in the future, when should he arrange another angiogram? It seems that one thing leads to another. One test leads to the next and then the next and so on. The patient had evidence of coronary disease and it was demonstrated to be flow limiting so according to the best evidence from the studies it is possible to justify all the steps that were taken. Has all of this testing resulted in an improvement in the patient's health, is the risk of death, myocardial infarction or need for urgent revascularisation reduced. Will there be unwanted effects of the drugs being used. Did the patient really benefit from stent insertion especially as he had never had any symptoms of chest pain? When people have health screening it is very important that they understand what the possible outcomes of doing these investigations.  When you make an initial diagnosis in someone with chest pain, before you do any tests, the chance your diagnosis is correct is called the pre-test probability. As more information comes in from investigations the probability can then be adjusted up or down to decide on further investigation or treatment. An important choice is what investigation to do? In cardiology we have developed a multitude of tests to look for coronary artery disease. We can put our belief in anatomy and do a CT coronary angiogram. his can detect coronary plaque greater than 1mm and has an excellent negative predictive value if it is normal. Alternatively, we could use a physiological test such as exercise ECG, stress echo or nuclear perfusion scans. Depending on where you work, the quality of the local service and your own specialist interests you will make a decision between these different tests. But which is correct? Is it better to use an anatomical or a physiological approach? The PROMISE trial was set up to answer this question. It's a huge trial with 10,003 patients recruited and was published yesterday in the NEJM. They are typical patients just like we see in chest pain clinics. The results are therefore very important for cardiologists. Patients were randomised to either a CT coronary angiogram (4,996 patients) or a physiological test (5,007 patients) with either a stress perfusion scan, stress echo or exercise ECG according to the local preference of the investigators. Patients were followed up for a median of 25 months and the endpoints of the trial were clinical ones including death, non-fatal MI and admission to hospital with unstable angina. An interesting initial result was that the pre-test probability of significant obstructive coronary artery disease was estimated at 53%. In other words 1 in 2 patients were though initially to have significant coronary artery disease. In patients assessed with CT, 12.2% (n=609) were referred on for invasive angiography because significant disease was detected compared with 8.1% (n=406) in the functional testing group. Of the 609 people who had an angiogram after the CT, 28% (170) did not have any significant coronary stenosis and 72% (439) had significant disease. Of the people with significant disease 71% (311) had revascularisation (239 PCI, 72 CABG) and the rest were managed medically. The overall rate of revascularisation from the CT approach was 6.2%. In the functional assessment group 8.1% (n=406) had abnormalities consistent with coronary artery stenosis. Of these 53% (213) had no significant disease on angiography. Of the remained, 193 had coronary artery disease and 82% (158) were offered revascularisation (120 PCI, 38 CABG). The overall rate of revascularisation in this group was 3.2%. So overall in the CT group 8.8% of people investigated had significant coronary stenosis compared to 3.9% in the functional group. So after all the investigation <10% of people had disease compared to the more than 50% suggested by the pre-test probability. This tells us clearly that the models used to assess coronary disease risk which are based on studies done in the 1970s and 80's markedly over-estimate the likelihood of coronary disease. The impression that the risk of coronary disease leads to the high level of investigation which then turns out to be normal in 90% of people. The detection rate for coronary disease by functional testing is about half of that with the CT which then results in half the rate of revascularisation. This is not unexpected since when we assess patients with anatomical tests we tend to overestimate the significance of coronary artery stenosis and this usually leads to a higher rate of revascularisation. Since the primary endpoint of the trial was a clinical one (death, non-fatal myocardial infarction or admission to hospital with unstable angina) and there was no significant difference between the two approaches it seems that either approach is reasonable. But beware if you start with a CT you are 50% more likely to be referred for an invasive angiogram and after that twice as likely to be offered revascularisation with no significant difference in clinical event rates. This of course has cost implications. If we assume that the anatomical and function testing is of similar cost initially but CT leads to more angiography and revascularisation then using some simple tariff costs the CT approach in the end costs almost twice as much. An interesting point to ponder for CCGs who might want us to use CT as the first line investigation in the belief that it reduces the need for invasive angiography.  Astrology is in the news today with MP David Tredinnick claiming that astrology could have “a role to play in healthcare”. He said that, along with complementary medicine, astrology "could take pressure off NHS doctors". This idea seems unlikely to me. I can't see any scientific basis for astrology nor the conclusions drawn from analysis of your birth sign. In Elizabethan England astrology was very popular. Your physician was as likely to cast your horoscope in order to assess and treat your disease. Astrology was connected with the four humours and the concept that the body was maintained in a state of health by balance of these substances which could be affected by outside influences. At that time it was not possible to explain the workings of the human body by way of scientific disciplines so other explanations often based on bad airs, magic, astrology and religion were used. For those interested there is a very informative book on this topic called Magic and Medicine in Elizabethan London. The astrologer physician Simon Forman kept a series of casebooks which are still held at the Bodleian library. These casebooks have been studied by Lauren Kassell and her team in Oxford and they have digitised them on the web. They make a fantastic resource for scholars of medical history are of little practical relevance for practicing physician today. It would be ludicrous to think that your birth sign could have any significant effect on your risk of disease or indeed your response to treatment; Wouldn't it? Thinking about this today I remembered an interesting analysis of the ISIS-2 clinical trial. In this study the effect of Aspirin was compared to that of placebo in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Overall the trial was positive showing a strong benefit. The authors went on to show that aspirin was, however, ineffective in patients born under the star signs of Libra and Gemini (150 deaths on aspirin vs 147 on placebo), but was beneficial in the remainder (654 deaths on aspirin vs 869 on placebo). As the authors said "most people laughed when they were shown the results" but if a more plausible separation of data is presented (e.g. men versus women, or African Americans versus Caucasians) they are more likely to believe them even though they still reflect the analysis of subgroups. But it doesn't stop with drug therapy. A study of endarterectomy for severe carotid stenosis showed a remarkable trend in benefit (p<0·0000001), highest in patients born in May or June and falling smoothly to possible harm in March and April. Was this the influence of birth on outcome of a surgical procedure - I don't think so. If your interested in more of these subgroup anomalies they are well described in this review by Peter Sleight. Before we start to claim this is evidence for astrological influences at the time of our birth we need to remember that these results were based on subgroup analyses which are unreliable. The power calculation for a clinical trial is determined for the primary endpoint and statistical analysis of secondary endpoints or subgroups may be interestingly but misleading. Perhaps the best place for astrology is in the newspapers - a light relief between the cartoons and the TV guide. |

Dr Richard BogleThe opinions expressed in this blog are strictly those of the author and should not be construed as the opinion or policy of my employers nor recommendations for your care or anyone else's. Always seek professional guidance instead. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed