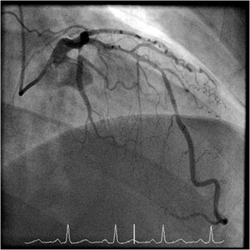

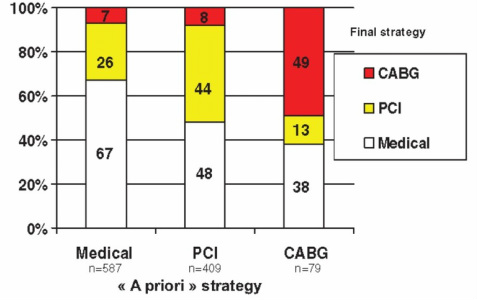

When a patient has a coronary angiogram the cardiologist will report the results in terms of the degree of narrowing of the arteries. For example a 60% stenosis in the LAD, a 40% stenosis in the circumflex. But what does that really mean? Is the stenosis flow limiting? Is it responsible for the patients symptoms? Is the lesion prognostically significant? Should a stent be place? Is a bypass indicated? Many questions but the fundamental one is: "Would this patient's outcome be better with or without revascularisation or is medical therapy more appropriate?" When there is mild or critical coronary artery disease then the decision making is straightforward. However in many cases there are moderate areas of coronary narrowing. Showing the angiogram to several cardiologists will usually result in differing opinions about whether a lesion is flow limiting or not. For some cardiologists the "Oculostenotic reflex" is already potentiated leading to "iatrogenosis fulminans." In 1995 Steve Nissen and Eric Topol wrote about cardiologists preoccupation with luminography and eloquently showed how lesion assessment with angiography performed very poorly compared to intravascular ultrasound. They also wrote of the dissociation between the angiogram and clinical outcome and called for a shift in our with luminology towards measures that improve survival, freedom from myocardial infarction and symptoms of angina. Whether a coronary lesion is flow limiting is not just dependent on the degree of arterial stenosis but also on the amount of cardiac muscle supplied, the presence of collateral vessels, the length of the lesion and the function of the endothelium. Some of these factors can be assessed subjectively by angiography but others cannot. What is required is a more functional or physiological assessment. Cardiologists have fooled themselves for too long that they are able to determine the functional significance of a moderate coronary stenosis from the angiogram alone. Recent data using the pressure wire has challenged some of this thinking although there are still some sceptics. The FAME studies showed that use of the pressure wire to measure fractional flow reserve (FFR) could be useful to help in selecting the appropriate therapy and guiding coronary revascularization in patients referred for a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) procedure. Very recently a real world study has been published using FFR in patients referred for diagnostic angiography and looking at its impact on the decisions involved in revascularization. In this study patients referred for diagnostic angiography had a treatment plan for intermediate lesions (35-65% by eye) made on the basis of the angiography alone. 55% of patients were recommended to receive medical therapy and 45% revascularization (PCI, 38%; CABG, 7%). FFR measurement was then performed with the pressure wire and after this 58% of patients were recommended for medical therapy and 42% for revascularization (PCI, 32%; CABG, 10%). The results were not so different overall but in individual patients the FFR strategy changed the recommended treatment in 43% of cases. Reclassification was observed in 33% medical patients, 56% of PCI patients and 51% of CABG patients. These results are hugely important since they indicate that even experienced cardiologists are unable to judge the flow limiting nature of moderate lesions. In the initial medical treatment group one third of patients met FFR criteria for revascularisation. In the PCI group, half of patients were due to receive inappropriate or a less optimal type of revascularisation. In the surgical group over half of patients could have avoided an operation. What this study is telling us is that using the eyeball technique to judge the severity of coronary disease is not the best way to decide on a management plan for cardiac patients. If the practice of using a pressure wire became standard in diagnostic coronary angiograms it would lead to more patients receiving medical therapy, less receiving angioplasty and more patients having CABG. The effects on the economics of management of coronary disease are complex. Assuming everyone gets medical therapy then the cost of the increased CABG although a more expensive procedure is offset by the reduction in expenditure on angioplasty. The repeat revascularisation costs are likely to be lower since this has been shown routinely in most of the CABG versus PCI studies. There is of course the cost of the pressure wire for every case. Overall the most improtant thing is that the patient receives the most appropriate treatment and not at the mercy of the oculostenotic reflex.

1 Comment

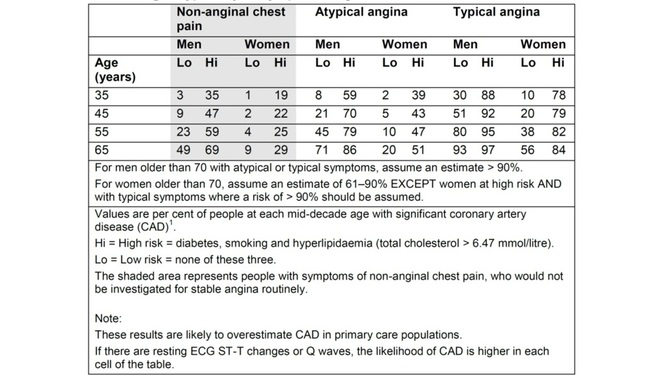

In 2010 NICE published a guideline on Chest Pain of Recent Onset. This was an important document for GPs and cardiologists. It has been widely cited and has had an effect on how Rapid Access Chest Pain clinics operate. NICE used their usual cost-effectiveness approach to review and then recommend which cardiac investigations were most appropriate in the assessment of patients with chest pain. Some of the recommendations e.g. to not use exercise treadmill testing to assess patients have been largely ignored by many cardiologists but the guidelines have stimulated an increase in the use of non-invasive imaging tests such as CT coronary angiography, myocardial perfusion scanning and stress echocardiography. A recent article in the BMJ “Rational Imaging” series sought to review the investigation of stable chest pain of suspected cardiac origin. Essentially this was a rehash of the 2010 NICE guidelines with focus on the estimation of likelihood of a patient having coronary artery disease and a strong bias to recommended CT and cardiovascular MR imaging (not surprising since all of the authors have specialist interests in this discipline). I think it is time to redress the balance around imaging investigations and critically review the NICE guideline approach. The BMJ article describes the following case: A 45 year old man, who was a non-smoker and did not have diabetes or hyperlipidaemia, presented to his doctor with chest discomfort after exercise. There were no relevant findings on clinical examination and resting electrocardiography (ECG) results were normal. On the basis of age, sex, risk factors, and symptoms, the patient’s pre-test probability of coronary artery disease was 21% and he was referred for calcium scoring. The calcium score was 11 and he proceeded to computed tomography coronary angiography, which identified a 70% stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Adenosine stress perfusion cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed reduced perfusion of the septum within the territory of the left anterior descending coronary artery. He was managed for stable angina on the basis of these findings. I see very many patients with this type of clinical presentation and my approach would not be that recommended by the authors of this article. My clinical impression is that the patient has angina. I would recommend treatment with 75mg aspirin, a beta blocker and to give a GTN spray. I would recommend that the patient has an invasive coronary angiogram. The angiogram is done to define the pattern of coronary artery disease and to decide on the correct approach to further management which may or may not involve revascularisation. The patient starts treatment as soon as the diagnosis of angina is made to improve symptoms and reduce risk of cardiovascular events. So the diagnosis and treatment plan for the patient is completed in a timely manner and with a single test rather than three different tests. NICE and this rational imaging review recommend a different approach. First you estimate the likelihood of coronary artery disease. How? The authors use the table in the NICE guidelines (see below) and say it’s 21%. On that basis they recommend a CT calcium score. I would take issue with this on two counts. First I think the patient’s symptoms are consistent with angina and therefore his predicted risk, according to the NICE guidelines, is much higher at 51%. Second there is evidence that in a younger patient coronary artery disease may occur in the absence of calcification of the coronary arteries. So a zero calcium score does not confidently exclude coronary artery disease in a symptomatic patient. Calcium scoring of the coronary arteries is a relatively quick, cheap and simple test which is entirely non-invasive. CT coronary angiography involves pre-treatment of the patient usually with beta blockers to reduce the heart rate to 60 and pre-assessment of the renal function as intravenous contrast will be administered. The patient then has a CT coronary angiogram and now we see that rather than the predicted 21% chance of having coronary disease the patient does actually have the disease. He then has an adenosine perfusion cardiac magnetic resonance scan (not very widely available, certainly expensive but as all of the authors are experts in CMR scanning not surprising). This demonstrates cardiac ischaemia which is not surprising since there is a flow limiting lesion in a coronary artery and the patient has symptoms of chest pain. After that the patient is managed for stable angina. This management, not discussed in the article, most likely involves an invasive angiogram and consideration of angioplasty to relieve symptoms if not controlled by medical therapy. Whilst the approach described by the authors might be appropriate for an asymptomatic patient it seems a long and complicated route to identify and treat the disease which most cardiologists could have predicted was there from simply taking a proper history. The best predictor of the presence of obstructive coronary artery disease is the presence of symptoms of angina. That’s not to say that patients without angina don’t have coronary artery disease. They do and many patients with significant coronary artery disease do not have classical symptoms of angina. In my view there are two principle questions to address. First, what is the cause of the patient’s symptoms of chest pain? If the answer is coronary artery disease then appropriate investigation needs to be undertaken. If the answer to this is no, then apart from trying to determine the non-cardiac cause of chest pain the other question is could this patient have underlying coronary artery disease? If the risk is high then appropriate preventative measures need to be recommended with regards to lifestyle and other risk factors. It is frustrating that many patients leave a chest pain clinic or accident and emergency department with a diagnosis of “non-cardiac chest pain."  Table from NICE Chest Pain Guidelines. Note the limited ages available for lookup and that "High Risk is defined as diabetes AND smoking AND hyperlipidaemia. This is often misquoted as it has been in the BMJ Rational Imaging Article as diabetes OR smoking OR hyperlipidaemia. Using the table in the NICE guidelines to predict risk of coronary artery disease is risky business itself. First only mid-decade ages are given so most patients fall between the categories of risk. Then with the risk factors you either have none and are low risk or you are a diabetic smoker with a cholesterol of >6.47mmol/l (it’s a strange number because the original study is from the USA and used an LDL cut off of >250mg/dl) and you are high risk. A single risk factor doesn’t count as high risk and so it is impossible from the table to estimate the risk for the majority of patients we see.

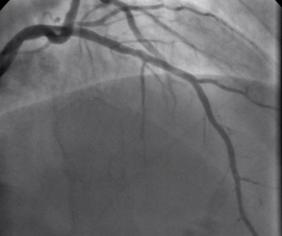

You can get around this by going back to the original paper which contains the risk model equations and building your own model to allow the exact age and individual risk factors. NICE didn’t do this in the guideline because it would be too complicated but it is ideally suited to an online version which I will publish soon on my website. Sadly however that doesn’t solve the problem. If you deconstruct the data in the table and go back to the original source you will be surprised and also disappointed. The original data comes from a paper published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in 1993 and reports the experiences of the Duke University Chest Pain Clinic. At Duke they collected sequential data on 1030 patients attending the clinic who were assessed for suspected ischaemic heart disease. 168 patients went on to have a coronary angiogram and from this cohort the risk prediction model was built and this produced the data in the table above. The tiny small sample size and the population on which it is based should make anyone use the NICE table with great caution. One wonders how many 35 year old females with no risk factors and typical angina were really studied by angiography in the 1980's when the data was collected. Certainly to use the numbers as a basis for determining the behaviour of different non-invasive investigation techniques would lead to a very high likelihood of inaccuracy. In the end there is as they say no substitute for experience. The most appropriate way to manage a patient with chest pain is for the assessment to be performed by an experienced cardiologist who can recommend the most appropriate strategy for that individual patient to get to the diagnosis and formulate a treatment plan as quickly and efficiently as possible. References: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chest pain of recent onset: assessment and diagnosis of recent onset chest pain or discomfort of suspected cardiac origin. CG95. 2010. Declan P O’Regan, Stephen P Harden, Stuart A Cook, Investigating stable chest pain of suspected cardiac origin BMJ 2013;347:f3940 Pryor DB, Shaw L, McCants CB et al. (1993) Value of the history and physical in identifying patients at increased risk for coronary artery disease. Annals of Internal Medicine 118(2):81–90.  The debate over whether patients with 3 vessel coronary artery disease should be treated with multi-vessel stenting (PCI) or coronary bypass surgery (CABG) has raged for the last decade. Stenting only needed to be as good as surgery for it to become the treatment of choice since the procedure is less invasive and the recovery time quicker. Comparison of the two forms of treatment has been difficult because stents have been constantly improved meaning that every trial was out of date compared to currently available technology at the time the results were published. This week the final 5 year results of the SYNTAX trial were published in the Lancet. This trial randomised 1800 patients to stents or surgery. The average age of the patients was 65 years, 75% were men and 25% diabetic. The combined end point included all-cause mortality, stroke, myocardial infarction and repeat revascularisation. The results showed that 26·9% in the CABG group and 37·3% in the PCI group reached that endpoint (p<0·0001). Myocardial infarction was higher in the PCI group (9.7% vs 3·8%; p<0·0001), as was the need for repeat revascularisation (25·9% vs 13.7%; p<0·0001). All-cause death and stroke were not different. So what can we learn from this trial. First the CABG group appear to get continued benefit as time went on. One explanation for this is that since CABG bypasses, any disease progressing in the artery proximal to the insertion point of the bypass graft remains treated which is not the case if a stent has been implanted. This may not be the whole explanation since CABG did not show a benefit over PCI in the left main stem treatment group although there were only 222 patients in this group. Second, SYNTAX acknowledged that not all 3 vessel disease is the same with some patients have discrete, simple lesions and others having very complex disease. Embedded in this trial was a scoring system (www.syntaxscore.com) which allowed a measure of the severity of the coronary artery disease. Treatment of low score (22 or less) or an isolated left main stem stenosis with CABG did not appear to confer an advantage over stents. In contrast an intermediate or high SYNTAX score predicted a significantly worse outcome if treated with stents rather than CABG. The results indicate that patients with simple three vessel disease could reasonably be treated with stents rather than surgery although it is important to remember that the analysis of subgroups in clinical trials is only hypothesis generating. The subgroups do not have enough patients in them to be adequately powered to draw definitive conclusions. Calculation of the SYNTAX Score gives the cardiologist an estimate of the severity of disease and helps feed into the decision making process regarding the best means of revascularisation. The other issue is that of patient choice. More patients randomised to CABG withdrew from the trial compared to PCI. Faced with a decision regarding what treatment to have the patient will have views and these need to be informed by a discussion of the best available evidence. If a patient understands that stents may have a less good outcome they may still decide to have this treatment because it is less invasive than CABG. The SYNTAX trial also leaves open the question of how to manage much older patients where the risk of stroke and mortality is greater. Many patients we currently see are in their late 70s or 80s, often with severe coronary disease and they may be less included to undergo CABG. Also most of the participants in SYNTAX were male and therefore it is difficult to know whether the outcomes for women would be the same. The SYNTAX trial is an important landmark to inform how we should manage severe coronary artery disease. However we need to remember that as cardiologists we treat individual people and the results of the clinical trials present results from pooled groups of patients may not always be representative of the patient in front of us. Coronary artery bypass graft surgery versus percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with three-vessel disease and left main coronary disease: 5-year follow-up of the randomised, clinical SYNTAX trial  When a person has a heart attack they often ask why it happened? This is a normal reaction because if you understand why an illness occured then it might be possible to take action to prevent it from occurring again or progressing. Apart from the traditional cardiac risk factors such as age, male gender, smoking, high blood pressure, diabetes and high cholesterol, patients often ask me if job stress has been involved. The Whitehall study performed in the 1980s showed that chronic work stress was associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease especially in men under 50 years old. This was also seen in the INTERHEART study which found that stress at work was associated with more than twice the risk of heart attack. The Womens Health Study also confirmed that the effect of stress on heart disease was not limited to men. Last October The Lancet published a large, individual patient-level meta-analysis of 197473 European men and women without pre-existing coronary heart disease to try and investigate the effect of job strain on development of coronary heart disease. In the study 15% of partipants reported job strain which might be seen as a relatively low overall level of stress. The study assessed both the demands placed on the workers and the degree of control they had over their work. Four groups were identified. Low job strain (low demands/high control), passive (low demands/low control), active (high demands/high control) and high strain (high demands/low control). Compared to the low job strain group, the high control/high demands group did not have increased risk of coornary heart disease. In contrast those workers with low demand/low control jobs had increased risk and the risk was even higher in those with doing jobs with high demands and low control. These results indicate that it is the degree of control a worker has over the demands placed on him or her that determines whether the job increases the risk of coronary disease. A high work pace is not necessarily a stressor if the worker has control. A difficult task might be seen as a challenge rather than being excessively strenuous. Much of this work was carried out in industrial settings and the modern world of work is different and other factors such as the effort-reward imbalance model and job insecurity are likely to be of major importance in the future. So when a person asks: Did stress cause my heart attack? More than a simple yes or no answer is required. You need to understand what job they have been doing and at what level. Getting an idea of the degree of control the individual had to regulate the demands of the job is critical in understanding the role of stress in heart disease. Job Strain and Coronary Heart Disease - Lancet Whitehall Study - Stress & Health Study Job Strain, Job Insecurity, and Incident Cardiovascular Disease in the Women’s Health Study: Results from a 10-Year Prospective Study INTERHEART Study  Colchicum autumnale Colchicine from the autumn crocus (Colchicum autumnale) has been used in medicine for 2000 years. It is mentioned in the Ebers papyrus dating from ~1550BC and it was recognised as a treatment for gout in Dioscorides's De Materia Medica in the first century. Colchicine has shown beneficial effects in treatment of familial Mediterranean fever and recurrent pericarditis. More recent studies have investigated whether colchicine decreases atrial fibrillation after ablation and this week a new trial in JACC has shown that colchicine reduces cardiovascular events in patients with chronic stable angina. In stable coornary artery disease a previous study showed that colchicine 0.5mg twice daily reduced CRP levels by 60%; interesting but hardly proof of a beneficial clinical effect. A clinical trial published in JACC this week has taken this one step forward and investigated the effects of colchicine in patients with stable angiographically proven coronary artery disease. The Low Dose Colchicine (LoDoCo) study investigated 532 patients randomized to open label colchicine (0.5mg per day) treatment or no colchicine for two years. After a 3 year median follow-up the primary outcome (acute coronary syndrome, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, or noncardioembolic ischemic stroke) occurred in 16% of placebo versus 5.3% of colchicine treated patients (67% significant RRR; NNT 11). The primary endpoint was driven by the reduction in ACS events as you might expect. On the safety side there was an 11% drop out rate from the colchicine treated group due to adverse GI effects of the drug during the first 30 days of treatment. The mechanism of action of colchine in reducing ACS events is unclear and the authors postulate it is secondary to an anti-inflammatory effect reducing cytokines and certaining this trial provides some support for the paradigm that reducing inflammation is beneficial in ACS. However we are still a long way from being able to conclude that colchicine is a therapy for stable CHD patients. A larger double blind clinical trial is needed before it could enter clinical practice for this indication. But who would fund such a trial with with a drug that is generically available. This would seem like an ideal trial for an investigator led study funded from MRC/BHF or Wellcome. However it might just interest the Pharma and in this respect colchicine has history. In July 2009 the FDA officially announced that colchicine was effective in treating acute gout. But didn't we know that 1500 years ago! Well colchicine had never been officially approved by the FDA. Although the 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act required new drugs be approved it allowed drugs already marketed to remain available. Colchicine was one of a number of drugs that the FDA never formally evaluated. In 2007 URL Pharma did studies with colchicine to investigate the drug's safety and efficacy in gout in a randomized controlled trial. On the basis of their results the FDA approved Colcrys (the URL brand of Colchicine) for treatment of acute gout. Because this was technically a new indication for the drug, the Hatch-Waxman Act authorized the FDA to give the company 3 years market exclusivity which led to the price of colchicine to rise 50-fold from 9 cents to $4.85 per tablet. Ample enough reward considering the trial only had 185 participants with. A appropriately powered trial of colchinine in stable coronary disease would require a considerably greater number of participants and long period of follow-up so the rewards to Pharma might not be enough to make this viable. So colchicine remains an interesting drug and 2 millenia after its discovery we are still learning new things about its pharmacology but whether it will enter the cardiologists arena for treatment of coronary artery disease remains to be determined. Low-Dose Colchicine for Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. JACC 29 Jan 2013: Vol. 61, pp. 404-410. Incentives for Drug Development — The Curious Case of Colchicine. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:2045-2047  Non flowing limiting mid LAD stenosis Most patients who present with an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) undergo coronary angiography and the majority are then treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The remaining patients either have coronary artery disease which is not suitable for revascularisation or have lesions which do not appear to be angiographically flow limiting. ACS is thought to arise following rupture or erosion of thin-cap fibroatheroma (TCFA) on vulnerable plaques. When the angiogram shows non-flow limiting, but irregular and hazy lesions, some cardiologists feel uncomfortable treating the patient with medication alone. There is often discussion in the catheter laboratory about whether a coronary stent should be deployed with the rationale that this might "seal" or stabilise" the plaque and reduce the chance of future cardiac events. Advanced imaging with intravascular ultrasound-virtual histology (IVUS-VH) or optical coherence tomography (OCT) may help to identify TCFAs but there is no evidence that treating such lesions with bare metal or drug eluting stents reduces furture coronary events. Any potential benefit of stent treatment needs to be balanced against the risk of procedural complication, re-stenosis and stent thrombosis. A recent trial has sought to address the question of how to treat the vulnerable plaque. The SECRITT study published in Eurointervention in December 2012 investigated the effects of a stenting vulnerable plaque. 23 patients with high risk IVUS-VH and OCT proven TCFA and a non-flow limiting lesion proven with quantitative coronary angiography and FFR by pressure wire were randomised to treatment with a nitinol self-expanding vShield stent. This device has ultrathin 56 micron struts designed to reduce vessel damage and encourage laminar flow. The stent is self expanding and this avoids the need to deploy using conventional high pressure balloons. Following randomisation patient received either the vShield stent (n=13) or standard medical therapy (n=10). The baseline stenosis in the vShield group was 33.2±13.5% and the FFR 0.93±0.06. At six-month follow-up vShield patients had 18.7±16.9% stenosis and FFR was unchanged. The fibrous cap thickness at baseline was 48±12µm increasing to 201±168µm. No dissections occured and there were no plaque ruptures with the VShield. There were no device-related major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) events at six-month follow-up. In the control group of 5 patients the % diameter stenosis, FFR were unchange at 6 months and there was no significant difference in late loss between the Vshield and medical treated groups. SECRITT is proof of principle study which has demonstrated that passivation and sealing of TCFA with a vShield self-expanding nitinol device appears feasible and safe. Whether treatment of vulerable plaque with conventional stents would have the same results is unknown. A comparison of the VShield with conventional balloon expandable stents has shown conventional stents result in a high proportion tissue prolapse or intra-stent dissection visible with OCT which are less frequently seen with the VShield stent. However, these vessel-wall injuries were not associated with in-hospital clinical events and currently it is difficult to know if OCT-detectable acute vessel-wall injury after stenting is associated with untoward clinical safety events. A long-term, larger randomised study is needed to evaluate the efficacy of stenting the vulnerable plaque is needed, until we have that data intensive medical therapy remains the standard treatment for non-flow limiting lesion. SECRITT Trial Slide Set Comparison of Acute Vessel Wall Injury After Self-Expanding Stent and Conventional Balloon-Expandable Stent Implantation: A Study with Optical Coherence Tomography |

Dr Richard BogleThe opinions expressed in this blog are strictly those of the author and should not be construed as the opinion or policy of my employers nor recommendations for your care or anyone else's. Always seek professional guidance instead. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed