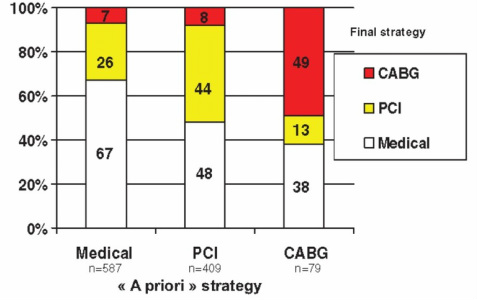

When a patient has a coronary angiogram the cardiologist will report the results in terms of the degree of narrowing of the arteries. For example a 60% stenosis in the LAD, a 40% stenosis in the circumflex. But what does that really mean? Is the stenosis flow limiting? Is it responsible for the patients symptoms? Is the lesion prognostically significant? Should a stent be place? Is a bypass indicated? Many questions but the fundamental one is: "Would this patient's outcome be better with or without revascularisation or is medical therapy more appropriate?" When there is mild or critical coronary artery disease then the decision making is straightforward. However in many cases there are moderate areas of coronary narrowing. Showing the angiogram to several cardiologists will usually result in differing opinions about whether a lesion is flow limiting or not. For some cardiologists the "Oculostenotic reflex" is already potentiated leading to "iatrogenosis fulminans." In 1995 Steve Nissen and Eric Topol wrote about cardiologists preoccupation with luminography and eloquently showed how lesion assessment with angiography performed very poorly compared to intravascular ultrasound. They also wrote of the dissociation between the angiogram and clinical outcome and called for a shift in our with luminology towards measures that improve survival, freedom from myocardial infarction and symptoms of angina. Whether a coronary lesion is flow limiting is not just dependent on the degree of arterial stenosis but also on the amount of cardiac muscle supplied, the presence of collateral vessels, the length of the lesion and the function of the endothelium. Some of these factors can be assessed subjectively by angiography but others cannot. What is required is a more functional or physiological assessment. Cardiologists have fooled themselves for too long that they are able to determine the functional significance of a moderate coronary stenosis from the angiogram alone. Recent data using the pressure wire has challenged some of this thinking although there are still some sceptics. The FAME studies showed that use of the pressure wire to measure fractional flow reserve (FFR) could be useful to help in selecting the appropriate therapy and guiding coronary revascularization in patients referred for a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) procedure. Very recently a real world study has been published using FFR in patients referred for diagnostic angiography and looking at its impact on the decisions involved in revascularization. In this study patients referred for diagnostic angiography had a treatment plan for intermediate lesions (35-65% by eye) made on the basis of the angiography alone. 55% of patients were recommended to receive medical therapy and 45% revascularization (PCI, 38%; CABG, 7%). FFR measurement was then performed with the pressure wire and after this 58% of patients were recommended for medical therapy and 42% for revascularization (PCI, 32%; CABG, 10%). The results were not so different overall but in individual patients the FFR strategy changed the recommended treatment in 43% of cases. Reclassification was observed in 33% medical patients, 56% of PCI patients and 51% of CABG patients. These results are hugely important since they indicate that even experienced cardiologists are unable to judge the flow limiting nature of moderate lesions. In the initial medical treatment group one third of patients met FFR criteria for revascularisation. In the PCI group, half of patients were due to receive inappropriate or a less optimal type of revascularisation. In the surgical group over half of patients could have avoided an operation. What this study is telling us is that using the eyeball technique to judge the severity of coronary disease is not the best way to decide on a management plan for cardiac patients. If the practice of using a pressure wire became standard in diagnostic coronary angiograms it would lead to more patients receiving medical therapy, less receiving angioplasty and more patients having CABG. The effects on the economics of management of coronary disease are complex. Assuming everyone gets medical therapy then the cost of the increased CABG although a more expensive procedure is offset by the reduction in expenditure on angioplasty. The repeat revascularisation costs are likely to be lower since this has been shown routinely in most of the CABG versus PCI studies. There is of course the cost of the pressure wire for every case. Overall the most improtant thing is that the patient receives the most appropriate treatment and not at the mercy of the oculostenotic reflex.

1 Comment

Ben

29/11/2013 07:44:07 pm

The way it should be in an ideal world, but this strategy might not be applicable to a high volume centre. Where Cath labs are of scarce in numbers. - @heart_kl

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Dr Richard BogleThe opinions expressed in this blog are strictly those of the author and should not be construed as the opinion or policy of my employers nor recommendations for your care or anyone else's. Always seek professional guidance instead. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed