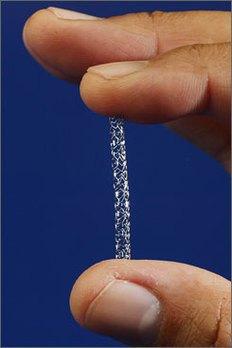

People often ask me how long will a coronary stent last? When counselling patients about a stent procedure I usually warn them about the risk of restenosis but there is no easy answer to the question of how long a coronary stent will last. Some last for as long as we have been following patients up (20 years) but in others restenosis occurs. The greatest value of the stent was to solve the problem of acute vessel closure in the first few hours after balloon angioplasty. This saved many patients from immediate coronary bypass surgery but the bare metal stent was associated with a high rate of restenosis almost comparable to that of balloon angioplasty. Fortunately the restenosis problem has been tackled by the introduction of drug-eluting stents coated with agents that inhibit cell proliferation. In-stent restenosis usually occurs within the first 200 days after an angioplasty. It can be symptomatic (clinical restenosis) or silent (angiographic restenosis). The practice of performing a routine check angiogram after stenting has nowadays largely ceased however two recently published papers, where routine check angiography has been performed, give important information about this topic. From 1998 to 2009 routine angiography was performed 6-9 months after coronary stenting. In the first 4 years bare metal stents were used then first, subsequently second generation drug eluting stents. Restenosis was defined simply as the presence of ≥50% lumen diameter stenosis at follow-up angiography. Data from 10 004 patients (15 004 lesions) are presented with 4649 treated with bare metal stents (6521 lesions) and 5355 with drug eluting stents (8483 lesions). With the bare metal stents 30.1% of patients had angiographic re-stenosis. The effectiveness of drug eluting stents is seen in terms of reduced re-stenosis falling to 14.6% for first and 12.2% for second generation drug eluting stents. What predicts restenosis? For bare metal stents it was small vessel size, long lesion and long stented length and of course type 2 diabetes. For drug eluting stents it was these same factors but the different anti-restenotic potency of the stent also made a difference with the lowest re-stenosis rates seen with Xience and Resolute stents at around 10%. But does re-stenosis matter; does it affect prognosis? From the same study comes a second paper looking at this question. 5% of patients presented with an acute coronary syndrome, 43.2% with stable angina pectoris and 51.8% were asymptomatic. Restenosis was independently associated with a 23% increase in 4-year mortality. Of the 5185 asymptomatic patients 18.4% had restenosis: of these 40.7% underwent further stenting but this did not impact on 4-year-mortality. There were 300 deaths among asymptomatic patients during the 4-year follow-up, 73 occurred in patients with restenosis and 227 in patients without restenosis. In patients with restenosis the decision to perform a further stenting procedure did not impact on 4-year-mortality risk. It is widely recognised that routine angiography after PCI leads to higher rates of repeat intervention and there is no clear advantages when compared with a surveillance strategy in which repeat angiography is reserved for the evaluation of recurrent symptoms or objective signs of myocardial ischaemia. It is interesting then that in the era of drug eluting stents when 90% of patients do not have restenosis that so many people were being exposed to an invasive procedure outside of a clinical trial simply because of an institutional policy. One wonders if for these institutions in Germany this practice was more important for income generation than for improvement of clinical outcomes. However the data generated has given some important real world data. It seems however that angiography after PCI should be restricted to patients with recurrent symptoms or signs of ischaemia and although the presence of asymptomatic restenosis detected at routine control angiography provides additional clinically relevant information concerning long-term mortality risk although it does not indicate that routine angiography is a predictor of long-term mortality.

4 Comments

Betty Crump

5/2/2018 11:10:09 am

does a stent have a life span of approx. 10 years?

Reply

sheila

3/3/2018 10:26:06 pm

I do not have a website. Had stent put in. What should the daily intake of calcium be?

Reply

Mary S. Ambrosio

13/6/2018 05:25:43 am

I follow a restricted diet, and feel very good like, a normal person ( thanks to Mont Sinai hospital )

Reply

Muhammad Shafi

30/6/2018 01:30:33 am

Sir

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Dr Richard BogleThe opinions expressed in this blog are strictly those of the author and should not be construed as the opinion or policy of my employers nor recommendations for your care or anyone else's. Always seek professional guidance instead. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed