|

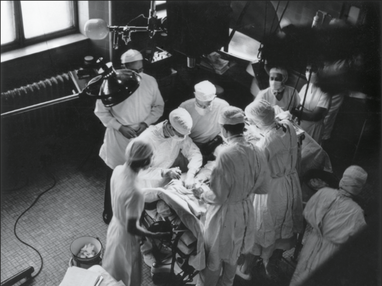

On the 29th October 1944 the first cardiac operation was performed at the Johns Hopkins Hospital for the treatment of congenital heart disease. Dr Alfred Blalock, the Chief of Surgery, carried out a pioneering surgical procedure designed to palliate a condition called Tetralogy of Fallot. This complex condition is characterised by a narrowing in the outflow tract of the right ventricle, thickening of the right ventricle, a ventricular septal defect and an over-riding aorta. In essence the blood flow to the lung is severely compromised and babies born with this condition are often deeply cyanosed and therefore known as "blue-babies." In the 1930’s the management of a blue baby was to place them in an oxygen tent. Children were advised to assume a squatting position to reduce venous return to the heart, and to try and keep as quiet and calm as possible to reduce infundibular spasm. The prognosis was terrible and the paediatric cardiologist at Johns Hopkins, Dr Helen Taussig, had to simply watch babies and children die. It was known that children with Fallot's who also had a patent ductus arteriosus were less cyanosed and this led to the idea of whether it might be possible to create a shunt between a great vessel and the pulmonary artery in order to supply blood to the lung. After painstaking laboratory work this resulted in the introduction of what is commonly called the "Blalock-Taussig shunt." In this procedure the left subclavian artery was anastomosed to the pulmonary artery. The operation was first performed at Johns Hopkins on 29th October 1944 and represented the first effective treatment for this condition and it is still used in a modified form today. It was published in JAMA in 1945.  This story would in itself be interesting but what makes it fascinating is the contribution of another member of the team. If you look at the photograph of the operating room you can see there is a man on the far left of the picture standing behind Blalock who is operating. That man was called Vivien Thomas. Nowadays we would call him an African American but in 1940’s Baltimore things were different.Thomas left school at 14 with no college education and started work as a carpenter. After losing his job he obtained a position in Dr Blalock’s laboratory as a janitor. Soon Blalock recognised his exceptional talent with his hands and he became the technician who ran Dr Blalock’s experimental surgical laboratory. When it came to the scientific and the surgical technical aspects of the shunt his own autobiography and detailed research has demonstrated that the primary contribution was from Thomas. Most of the fundamental studies were done by him and Blalock only did one practice procedure in a dog before performing the first surgery on a 15-month-old girl. As the photograph shows Thomas stood behind Blalock during the procedure to provide advice. At a time of racial segregation and discrimination in America, Thomas’s contribution to the development of the shunt procedure remained relatively unknown outside Hopkins. He was ignored by the world’s press and media and the procedure became known as the Blalock-Taussig shunt. He was not even acknowledged for technical contributions in the original paper. However in time, as political and civil rights movements led to change in attitudes towards race, Thomas's exceptional contribution to the development of this pioneering heart surgery was recognised. His portrait now hands in the hallowed corridors of the Johns Hopkins Hospital alongside Dr Alfred Blalock, Sir William Osler, Dr Harvey Cushing and Dr William Halsted – legends of modern clinical medicine. October is Black History Month. You have probably heard of Rosa Parks, Mary Seacole and Claudia Jones but the story of Vivien Thomas is not well known outside of Johns Hopkins. Thomas made a huge contribution to the birth of cardiac surgery and thus plays an important part in the history of medicine. He is a wonderful example of how despite segregation a black man fought against the odds and was key in developing a life-saving operation used to treat thousands of children worldwide. Perhaps it’s time to officially rename the Blalock-Taussig shunt the Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt and give him his rightful place in Black History month.

3 Comments

If a patient complains of breathlessness one possible cause is collection of fluid around the lungs called a pleural effusion. This diagnosis can be made easily by tapping the chest with the fingers - a technique known as percussion. Percussion was invented by Joseph Leopold Auenbrugger (1722-1809), the son of an innkeeper from Gratz, in Austria. In 1751, after completion of his medical studies, he became assistant physician at the Holy Trinity and Spanish Military Hospital in Vienna. He discovered that tapping his fingers on the patient's chest produced sounds of varying pitch depending on what structure was underneath. As a child he had seen the barrels in his father’s cellar being tapped to find out how much wine they contained and in his work on percussion he wrote that “empty casks are resonant but they become dull when full of wine”. By systematic percussion over the chest he observed that the note was dull over the heart. Likewise if the pleural cavity surrounding the lungs became filled with fluid, the sound of the percussion note was so muffled it became completely or stony dull. He went on to correlate his percussion findings with conditions found at post-mortem and to prove the existence of fluid inside the chest by withdrawing it with a trocar. Auenbrugger practised the percussion technique for seven years before, in 1761, he published his treatise titled: “Inventum Novum ex Percussione Thoracis Humani Ut Signo Abstrusos Interni Pectoris Morbos Detegendi” which translates as “New Invention, by means of percussing the human chest, as a sign of detecting obscure disease in the interior of the chest”. In the 18th Century publication of anything medically often invoked criticism rather than adulation from colleagues. In the preface of his book he wrote: “In making public my discoveries respecting this matter, I have been actuated neither by an itch for writing, nor a fondness for speculation, but by the desire of submitting to my brethren the fruits of seven years observation and reflection. In doing so, I have not been unconscious of the dangers I must encounter, since it has always been the fate of those who have illustrated or improved the arts and sciences by their discoveries, to be beset by envy, malice, hatred, detraction and calumny”. Auenbrugger’s method of percussion was to strike the chest wall directly with the extended fingertips. He found that the note produced was better if the shirt was tightly drawn across the chest (like the covering of a drum) or if the physician’s hand was covered with a leather glove. Today we lay one hand flat on the chest and strike the back of its middle finger with the tip of the middle finger of the other hand. This prodcues a better percussion note and makes it less uncomfortable for the patient compared to striking the chest directly with the fingertips. After his publication the percussion technique was ignored for many years. Baron van Swieten, Professor of Medicine at Vienna University and Auenbruggers teacher, did not mention it in his 1764 treatise on fluid around the lungs in pulmonary tuberculosis and other contemporaries like Vogel confused it with the Hippocratic practice of succussion whereby the patient was shaken vigerously to detect the presence of fluid and air in the thorax. One favourable review appeared describing the discovery as “a torch that was designed to illumine the darkness in which diseases of the thorax had up to this time lain concealed". The poor reception of his book and being dismissed from the Spanish Military Hospital did not seem to harm Auenbrugger's his career prospects. Private practice prospered and he was popular at the Court of Vienna where he was enobled by the Emperor Joseph II with the title “Edler von Auenbrugger". He was also an accomplished musician and at the Emperor’s request wrote the libretto for a comic opera, Der Rauchfangskehrer (The Chimney Sweep) for the court composer Salieri. Percussion remained hidden until 1808 when Jean Nicholas Corvisart, the personal physician to Napoleon, translated Auenbrugger's work from Latin into French and then the technique rapidly came to world-wide attention and use. Today percussion remains a basic clinical skill learnt by all medical students and practised by doctors on a daily basis.  In 1975 a simple ceremony was held at the Horton Hospital in Epsom. A plaque was unvieled commemorating the contribution made between 1925 and 1965 towards the "relief of suffering". The building housed the Mott Clinic also known as the Horton Malaria Laboratory. It was here, before the discovery of penicillin, that malaria infected mosquitos were used to treat patients with syphilis. In Vienna at the end of world war one Professor Wagner-Jauregg dicovered that malaria-induced fever was effective in the treatment of the syphilitic condiiton General Paralysis of the Insane (GPI). GPI was a serious problem affecting about 10% of patients in psychiatric hospitals and there was until that time no effective treatment. The malaria therapy was reported to result in over 80% of patients were free of disease progression. The treatment was introduced rapidly into England but there was lack of awareness of the lethal effects of certain species of human malaria parasites such as Plasmodium falciparum. Horton was chosen to treat these patients because after a pilot study at Cane Hill and Claybury hospitals they found that there was a high risk that malaria would spread between patients; Horton was ideal because of the fourteen bed isolation hospital and so to try and render the treatment as safe as possible the Mott Clinic and Horton Laboratory was established. Colonel S. P. James, was the first director and he found a strain of malaria in Madagasca that was safe for use in man. In May 1925, mosquitoes infected with this strain were taken to Horton and fed on two female patients.The function of the laboratory was to provide malaria parasites use in the treatment of GPI and this continued until penicillin made the treatment obsolete. Overall the clinic provided treatment for thousands of patients sufferering from GPI with more than 16,000 treated in Horton Hospital itself. A stream of publications appeared in scientific journals originating from the Horton Laboratory including the discovery of the exoerythrocytic parasite in the liver in man in 1948. The laboratory moved into the testing synthetic antimalarial drugs in conditions of maximum secrecy during the second world war. The laboratory closed in 1973 and its memorabilia and archives are held at the Wellcome Museum and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Epsom and Ewell Archives  When a patient is admitted to St George's Hospital for a daycase cardiac procedure the chances are they will spend part of the day on James Hope Ward. Situated on the first floor of Atkinson Morley Wing this busy ward sees a constant stream of patients admitted for coronary angiograms, angioplasty or cardioversion. Whilst recovering they might wonder who was James Hope, and what was his connection to cardiology and St George's Hospital? James Hope was born near Manchester in 1801. His name was never associated with a disease or syndrome or the naming of a physical sign but his skill was to take a new invention, the stethoscope, and to demonstrate its value in the diagnosis of diseases of the heart. After studying for five years in Edinburgh he undertook further study in London, Paris and Milan beofre being appointed as assistant physician to St George's Hospital at Hyde Park Corner. Over the next 5 years he saw over 20,000 patients that we admitted and a further 15,000 outpatients. He was appointed to the staff of the hospital as physician in 1839 at the age of 38. James Hope’s major contribution to cardiology was to understand the origin of the sounds heard when examining the heart. Laennec, the inventor of the stethoscope, thought that the first heart sound was due to the contraction of the ventricles and the second sound due to contraction of the atria. Hope conducted experiments on the exposed heart of a stunned donkey and correlated the sounds with the movement of the beating heart. He used a dissecting hook to block the aortic valve from closing and found that he was able to eradicate the second heart sound correctly concluding that the second heart sound was due to the closure of the aortic valve. Like many new inventions many doctors were afraid of using the stethoscope. To aid this in July 1838 James Hope hosted a public demonstration on the use of the stethoscope. This was described in the London Medical Gazette: "The following experiment... affords demonstrative proof that the diagnosis in question, usually supposed to require years of experience, may be efficiently taught in the brief space of ten minutes; and I communicate it to you in the hope that, through the medium of your valuable journal, it may by encouraging the diffident proof subservient to the progress of medical science." Sadly James Hope career was cut short by tuberculosis and he died in 1841. He was one of the first physicians interested in cardiology and is remembered for his important contributions to the science of cardiology. His memory lives on for all those staff and patients who come into contact with James Hope ward. Hope J. (1833). A treatise on the diseases of the heart and great vessels: comprising a new view of the physiology of the heart's action according to which the physical signs are explained. |

Dr Richard BogleThe opinions expressed in this blog are strictly those of the author and should not be construed as the opinion or policy of my employers nor recommendations for your care or anyone else's. Always seek professional guidance instead. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed