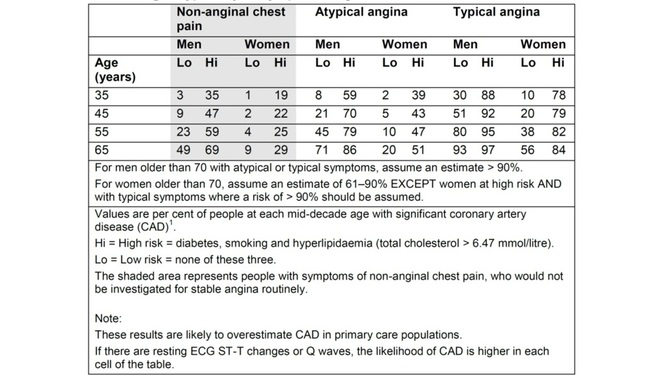

In 2010 NICE published a guideline on Chest Pain of Recent Onset. This was an important document for GPs and cardiologists. It has been widely cited and has had an effect on how Rapid Access Chest Pain clinics operate. NICE used their usual cost-effectiveness approach to review and then recommend which cardiac investigations were most appropriate in the assessment of patients with chest pain. Some of the recommendations e.g. to not use exercise treadmill testing to assess patients have been largely ignored by many cardiologists but the guidelines have stimulated an increase in the use of non-invasive imaging tests such as CT coronary angiography, myocardial perfusion scanning and stress echocardiography. A recent article in the BMJ “Rational Imaging” series sought to review the investigation of stable chest pain of suspected cardiac origin. Essentially this was a rehash of the 2010 NICE guidelines with focus on the estimation of likelihood of a patient having coronary artery disease and a strong bias to recommended CT and cardiovascular MR imaging (not surprising since all of the authors have specialist interests in this discipline). I think it is time to redress the balance around imaging investigations and critically review the NICE guideline approach. The BMJ article describes the following case: A 45 year old man, who was a non-smoker and did not have diabetes or hyperlipidaemia, presented to his doctor with chest discomfort after exercise. There were no relevant findings on clinical examination and resting electrocardiography (ECG) results were normal. On the basis of age, sex, risk factors, and symptoms, the patient’s pre-test probability of coronary artery disease was 21% and he was referred for calcium scoring. The calcium score was 11 and he proceeded to computed tomography coronary angiography, which identified a 70% stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Adenosine stress perfusion cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed reduced perfusion of the septum within the territory of the left anterior descending coronary artery. He was managed for stable angina on the basis of these findings. I see very many patients with this type of clinical presentation and my approach would not be that recommended by the authors of this article. My clinical impression is that the patient has angina. I would recommend treatment with 75mg aspirin, a beta blocker and to give a GTN spray. I would recommend that the patient has an invasive coronary angiogram. The angiogram is done to define the pattern of coronary artery disease and to decide on the correct approach to further management which may or may not involve revascularisation. The patient starts treatment as soon as the diagnosis of angina is made to improve symptoms and reduce risk of cardiovascular events. So the diagnosis and treatment plan for the patient is completed in a timely manner and with a single test rather than three different tests. NICE and this rational imaging review recommend a different approach. First you estimate the likelihood of coronary artery disease. How? The authors use the table in the NICE guidelines (see below) and say it’s 21%. On that basis they recommend a CT calcium score. I would take issue with this on two counts. First I think the patient’s symptoms are consistent with angina and therefore his predicted risk, according to the NICE guidelines, is much higher at 51%. Second there is evidence that in a younger patient coronary artery disease may occur in the absence of calcification of the coronary arteries. So a zero calcium score does not confidently exclude coronary artery disease in a symptomatic patient. Calcium scoring of the coronary arteries is a relatively quick, cheap and simple test which is entirely non-invasive. CT coronary angiography involves pre-treatment of the patient usually with beta blockers to reduce the heart rate to 60 and pre-assessment of the renal function as intravenous contrast will be administered. The patient then has a CT coronary angiogram and now we see that rather than the predicted 21% chance of having coronary disease the patient does actually have the disease. He then has an adenosine perfusion cardiac magnetic resonance scan (not very widely available, certainly expensive but as all of the authors are experts in CMR scanning not surprising). This demonstrates cardiac ischaemia which is not surprising since there is a flow limiting lesion in a coronary artery and the patient has symptoms of chest pain. After that the patient is managed for stable angina. This management, not discussed in the article, most likely involves an invasive angiogram and consideration of angioplasty to relieve symptoms if not controlled by medical therapy. Whilst the approach described by the authors might be appropriate for an asymptomatic patient it seems a long and complicated route to identify and treat the disease which most cardiologists could have predicted was there from simply taking a proper history. The best predictor of the presence of obstructive coronary artery disease is the presence of symptoms of angina. That’s not to say that patients without angina don’t have coronary artery disease. They do and many patients with significant coronary artery disease do not have classical symptoms of angina. In my view there are two principle questions to address. First, what is the cause of the patient’s symptoms of chest pain? If the answer is coronary artery disease then appropriate investigation needs to be undertaken. If the answer to this is no, then apart from trying to determine the non-cardiac cause of chest pain the other question is could this patient have underlying coronary artery disease? If the risk is high then appropriate preventative measures need to be recommended with regards to lifestyle and other risk factors. It is frustrating that many patients leave a chest pain clinic or accident and emergency department with a diagnosis of “non-cardiac chest pain."  Table from NICE Chest Pain Guidelines. Note the limited ages available for lookup and that "High Risk is defined as diabetes AND smoking AND hyperlipidaemia. This is often misquoted as it has been in the BMJ Rational Imaging Article as diabetes OR smoking OR hyperlipidaemia. Using the table in the NICE guidelines to predict risk of coronary artery disease is risky business itself. First only mid-decade ages are given so most patients fall between the categories of risk. Then with the risk factors you either have none and are low risk or you are a diabetic smoker with a cholesterol of >6.47mmol/l (it’s a strange number because the original study is from the USA and used an LDL cut off of >250mg/dl) and you are high risk. A single risk factor doesn’t count as high risk and so it is impossible from the table to estimate the risk for the majority of patients we see.

You can get around this by going back to the original paper which contains the risk model equations and building your own model to allow the exact age and individual risk factors. NICE didn’t do this in the guideline because it would be too complicated but it is ideally suited to an online version which I will publish soon on my website. Sadly however that doesn’t solve the problem. If you deconstruct the data in the table and go back to the original source you will be surprised and also disappointed. The original data comes from a paper published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in 1993 and reports the experiences of the Duke University Chest Pain Clinic. At Duke they collected sequential data on 1030 patients attending the clinic who were assessed for suspected ischaemic heart disease. 168 patients went on to have a coronary angiogram and from this cohort the risk prediction model was built and this produced the data in the table above. The tiny small sample size and the population on which it is based should make anyone use the NICE table with great caution. One wonders how many 35 year old females with no risk factors and typical angina were really studied by angiography in the 1980's when the data was collected. Certainly to use the numbers as a basis for determining the behaviour of different non-invasive investigation techniques would lead to a very high likelihood of inaccuracy. In the end there is as they say no substitute for experience. The most appropriate way to manage a patient with chest pain is for the assessment to be performed by an experienced cardiologist who can recommend the most appropriate strategy for that individual patient to get to the diagnosis and formulate a treatment plan as quickly and efficiently as possible. References: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chest pain of recent onset: assessment and diagnosis of recent onset chest pain or discomfort of suspected cardiac origin. CG95. 2010. Declan P O’Regan, Stephen P Harden, Stuart A Cook, Investigating stable chest pain of suspected cardiac origin BMJ 2013;347:f3940 Pryor DB, Shaw L, McCants CB et al. (1993) Value of the history and physical in identifying patients at increased risk for coronary artery disease. Annals of Internal Medicine 118(2):81–90.

1 Comment

|

Dr Richard BogleThe opinions expressed in this blog are strictly those of the author and should not be construed as the opinion or policy of my employers nor recommendations for your care or anyone else's. Always seek professional guidance instead. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed