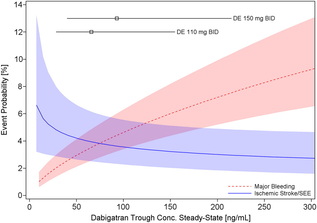

Probability of Major Bleeding Event and Ischemic Stroke/SEE Versus Trough Plasma Concentration of Dabigatran Calculated for 72-year-old male atrial fibrillation patient with prior stroke and diabetes. Lines and boxes at the top of the panel indicate median dabigatran concentrations in the RE-LY trial with 10th and 90th percentiles. Only time will tell as we get a more complete picture of the clinical pharmacology and real world experience of using the NOACs but like all new drugs we should exert a degree of caution and remember that we only know about half of what we need to know when the drug is launched.

0 Comments

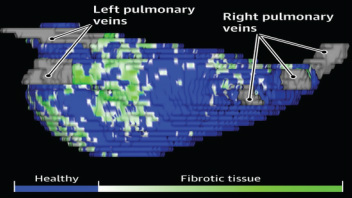

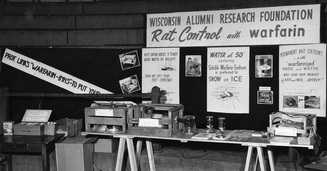

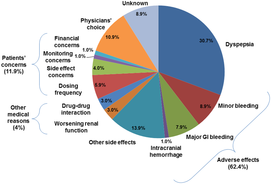

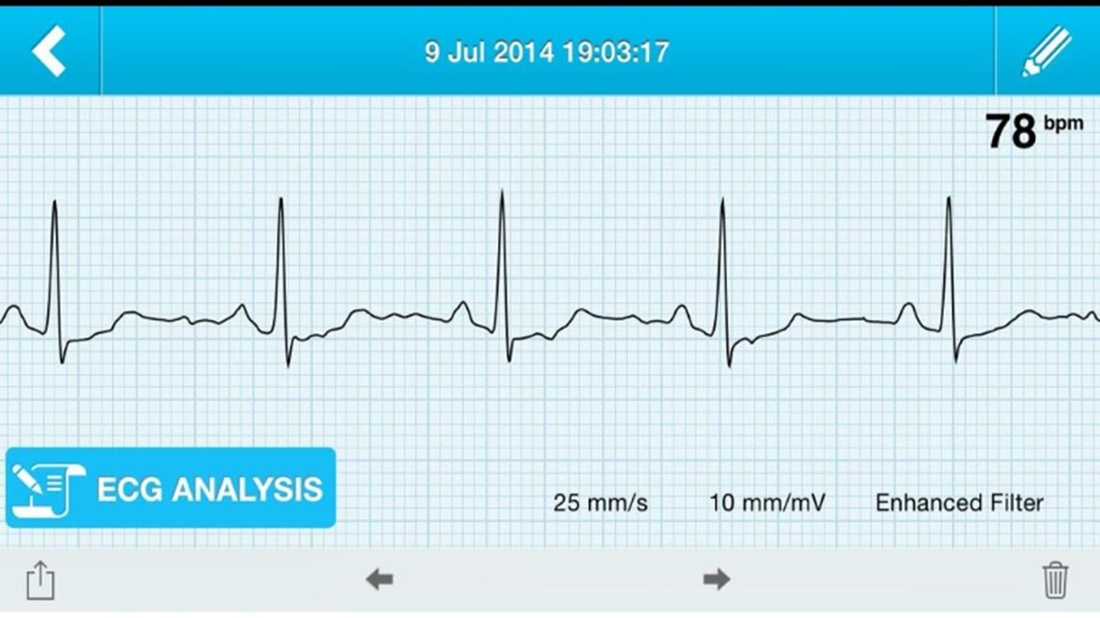

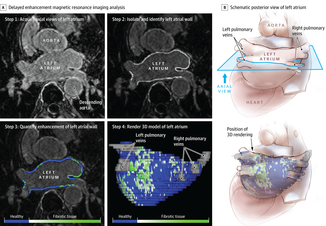

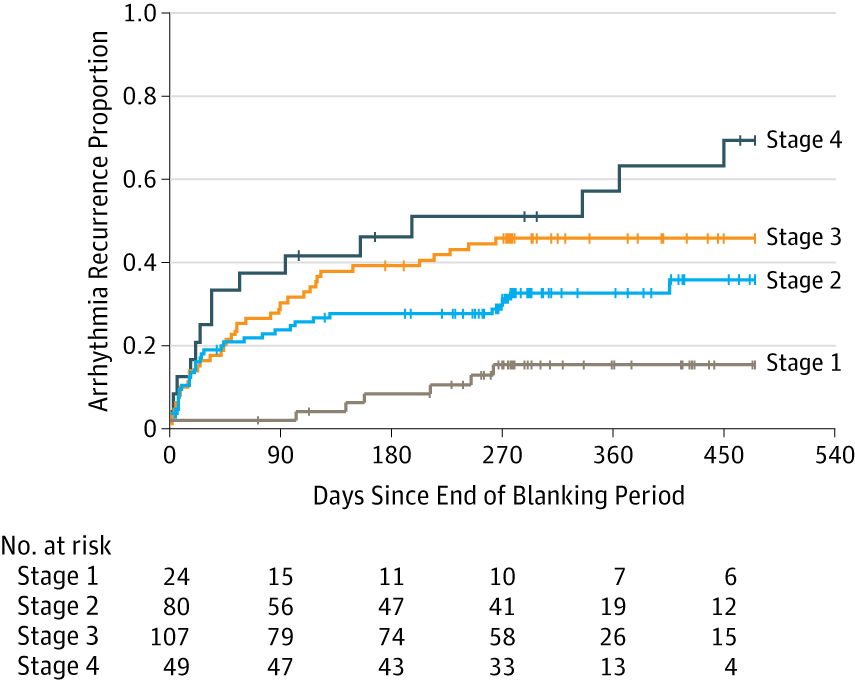

In Eric Topol's book The Creative Destruction of Medicine he speaks about how the precipitous convergence of a maturing Internet, increasing bandwith, near ubiquitous connectivity and miniature pocket computers (smartphones) are taking physicians and patients where no one has gone before. Palpitations are a common symptoms in patients attending my clinic. Assessment tries to establish when the symptoms started, how frequently they occurs, how long each episode is, whether there are provoking or relieving factors and whether there are any associated symptoms. I try to see whether the patient thought the rhythm disturbance was regular or irregular. Many times people are vague about the precise nature of the symptoms because it is very subjective and truly difficult to describe. For most patients the frequency of attacks is perhaps once or twice a week at most. What they need is an ECG recorded at the exact time they have symptoms. We still use the so called "24h Tape". in fact these can record for 7 days and don't contain any tape. We use cardiac event monitors such as the Novacor R-test which record loops of ECG for a week or more. One problem with all these devices is that they require wet gel electrodes to be stuck to the skin for long periods which often results in skin irritation and discomfort. The other problem is the so called vanishing arrhythmia that never comes when the monitor is attached. So is there another way to record the ECG which might be useful for someone with intermittent palpitations using a machine which people have to hand most of the time. This is where the AliveCor smartphone attachment comes in. I ordered one recently. It looks and behaves like a protective smartphone cover. Having already downloaded the AliveCor app I was ready to record my single lead ECG within a moment. The quality is remarkable and the device so simple to use. With two dry electrodes on the back of the phone, one for the left and the other for the right hand you can get a lead 1 type ECG. If you want a better P wave (ie lead II or III) why not put the device on the left leg and the right hand which also works superbly. No skin preparation is needed. One of the recordings I made is shown below - you can judge the quality for yourself. This is a typical recording and because it is on a smartphone it is possible to email the file or store it as a PDF. I guess the main limitation at present is the need to possess a smartphone and also the cost of the device which currently retails at £169. Certainly for patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation or episodic palpitations this device might be very useful. I am looking forward to using it. For further information about the device and how it works see the dedicate page on my website.  Atrial fibrillation (AF) is an important and preventable cause of stroke. If AF is detected then a patient will usually be advised to go onto anticoagulation which reduces the risk of stroke by about 70%. Some patients will have paroxysmal AF (PAF) which comes and goes interspersed by normal heart rhythm. PAF is defined as 30 seconds or more of AF and the risk of stroke is the same as with persistent AF. The ASSERT trial tried to determine how much PAF is necessary to increase the stroke risk and the results suggest that as little as 6 minutes of AF over a period of 3 months increases stroke risk by 2.5 fold. After a stroke it is routine to do an 12 lead ECG to assess the cardiac rhythm and if this is normal then a longer period of heart monitoring would be performed to look for evidence of PAF. The question is however how long should the monitoring be done for to stand a good chance of detect PAF? Is 24h enough, or should it be a week or a month or even longer. Two papers published this week in the New England Journal of Medicine have tried to address this question. The EMBRACE study compared a standard approach with 24h ECG monitor to a 30 day cardiac event recorder. 572 patients with apparently normal heart rhythm with a previous stroke in the last 6 months were randomly assigned to either 24h or 30 days of monitoring. In the group monitored for 24h just 3.2% of people had AF detected whereas in the group monitored for 30 days AF was detected in 16.1%. This meant that for every 8 people screened for the longer period 1 extra case of PAF was detected. Once AF was detected it led to a change of treatment for the patients with antiplatelet drugs being switched to anticoagulants which are much more effective at reducing recurrent stroke. In the CRYSTAL AF study patients were randomly assigned to either having a loop recorder implanted or standard care. After 6 months PAF has been detected in 8.9% of patients with the ILR compared to 1.4% in the control group and by 12 months this had increased to 12.4% in the ILR and 2% in the control group. There is a difference in the AF detection rate between the two studies which is probably due to the EMBRACE trial having an older population with more patients suffering from hypertension and diabetes. What is clear however is that the longer the period of monitoring the more cases of undiagnosed AF are detected. Since this has a profound effect on management of the patient these findings are very important. There are some practical problems with monitoring patients for 30 days due to the ability to comply with the need for electrodes of the chest. The EMBRACE study used a dry electrode chest belt which has better tolerability and less skin irritation than traditional electrodes. The ILR technique is attractive particularly and with the advent of virtually injectable devices such as the REVEAL LINQ but the cost of these devices might be seen as prohibitive if the technology was applied to every patient with a stroke. Perhaps though when a cost-effectiveness analysis is performed and the number of recurrent strokes prevented is factored in this type of monitoring device would pay for itself. If you take the parallel situation of a patient with a heart attack we think nothing of implanting several drug eluting stents which cost thousands of pounds in order to prevent a recurrent admission to hospital with chest pain or a non-fatal heart attack. What then of spending a similar amount to prevent a stroke? These new studies are challenging the current practice of accepting a short period of monitoring when looking for AF. In this situation absence of evidence of AF should not be taken as evidence of absence and it looks as though a more prolonged period of monitoring is likely to be beneficial.  This was also published on the British Geriatric Society Blog site If you watched the news this week you might have thought that the only recommendation in the NICE Atrial Fibrillation Guideline was that doctors should not prescribe aspirin to prevent strokes. In fact most cardiologists and geriatricians stopped using aspirin for this condition several years ago and the NICE recommendation simply reaffirms those issued previously by other professional societies such as the European Society of Cardiology. The real story behind the guidelines was, in my opinion, nothing to do with medication or rate versus rhythm but rather the importance of delivering a personalised package of care for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). Recognising that AF is a long term health condition there is emphasis on the importance of shared decision making processes particularly around anticoagulation. Alongside the guideline NICE published a Patient Decision Aid to assist with this process. The intention behind this is good but having shown the 36 page decision aid document to several patients today they were overwhelmed by the volume of information they were expected to digest. The aid includes much information that would not be relevant to the individual patient since it tries to cover the risks and benefit of all patients with various stroke and bleeding risks. It uses Cates plots to try and aid the decision making process but each chart has 1000 faces and only looks at the risks/benefits over one year so the faces benefiting from treatment are swamped by hundreds of faces not expecting any benefit. On a practical note NICE assumes that clinicians will have ready access to a colour printer otherwise the red/greens charts look somewhat monotone. The comparison of this decision aid with the highly professional and dynamic way information is presented on the JBS3 risk calculator website is striking and NICE need to up their game to make this and further decision aids much more user friendly. Summarising the information on two sides of A4 is aspirational but possible as has been done with other documents on breast and prostate cancer screening as has been promoted by the work of Gerd Gigerenzer. The guideline emphasises that the patient’s decision regarding anticoagulation will be affected by their own attitude towards risk and NICE say that if patients are provided with the appropriate information about the pros and cons they should be able to decide for themselves about whether to have treatment with anticoagulation or not. This removes the recommendation or opinion of the healthcare provider from the consultation and devolves the decision making to the patient. This represents a change in the doctor patient relationship and the dynamics of the consultation. In my experience, patients want to know the pros and cons of a particular treatment but are also interested in the opinion of the healthcare professional especially if they are well known and trusted. In everyday life we use rules of thumb – so called heuristics and recommendations from friends and family feed into the ability to make complex decisions. Often personal experience and anecdotes are trusted in preference to scientific evidence. To devolve the decision making completely to the patient might be seen as convenient for the healthcare professional. If the patient chooses anticoagulation and then bleeds – it was the patient’s decision to start the treatment, not the doctors. If the patient decides not to take anticoagulation and has a stroke then again it was their decision. In practice clinical medicine is complex and the interaction between a patient and an experienced clinician vital to make a detailed and appropriate assessment. Although stroke and bleeding risk can be calculated using scoring systems these measures are not perfect and derive from large populations which do not necessarily apply to the patient in the consulting room who may have complex multisystem disease and polypharmacy. The risk assessment tools are a starting point of the conversation about treatments. NICE should be commended for placing the patient’s involvement in deciding their management of AF centre stage. This is a clear move in the right direction for patients and should improve both outcomes of this common condition.  The success of ablation for atrial fibrillation (AF) is variable. It depends on the patient, it depends on the doctor. Traditional thinking was that people with a structurally normal heart on echo who had paroxysmal AF would do well with ablation. Those people with dilated left atrium and long standing persistent AF would not do so well. But how good are we really at selecting who will benefit from ablation? Pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) also known as AF ablation is the commonest catheter based procedure for the treatment of AF. The aim is to electrically isolate the pulmonary veins from the atrium because it is believed that ectopic beats arising in these veins are responsible for triggering episodes of AF. Despite the enthusiasm of some cardiologists for this procedure and the very large number of ablation procedures carried out daily around the world the long term results of randomised clinical trials are mixed to say the least with many patients relapsing back into AF within a year or requiring multiple procedures. Despite the best efforts of cardiologists the current clinical parameters we assess fail to define properly which patients will have successful maintenance of sinus rhythm after an AF ablation. Recent work performed at the University of Utah however is allowing us to think about the selection question differently. For a long time we have known that fibrosis in the atrium is important. The difficulty is how to measure fibrosis in people non-invasively. The Utah group have developed a method for assessing the amount of fibrosis in the left atrium using MR scanning. Using this information they are then able to show that the amount of fibrosis predicts which patients will respond well to ablation and remain free of AF and which patients will have a recurrence. The DECAAF study recently published in JAMA looked at 329 patients about two thirds of whom had paroxysmal AF and the rest persistent. They performed a special sequenced MR scan on all the patients. In 83% it was possible to obtained a scan of good enough quality to interpret. These patients then had an AF ablation were followed up for at least a year. At the end of the study about a quarter of patients were still on Class I or III (i.e. potent) anti-arhhythmic drugs indicating that ablation even if successful is does not mean no need for medication. Also about 5% of patients had a serious complication from the procedure. The MRI technique measured the amount of left atrial fibrosis and this was strongly associated with AF recurrence after removal of confounding variables such as age, hypertension history etc. When the patients were looked at 325 days after the ablation those with stage 1 (<10% fibrosis) had an AF recurrence rate of 15.3%, those with stage 2 (10-20% fibrosis) had a recurrence rate of 32.6%. By stage 3 (20-30% fibrosis) 45.9% were back in AF and stage 4 (>30% fibrosis) 51.1% were in AF. By 475 day the recurrence rate for stage 1 was 15.3% still but the stage 4 patients had increased to 69.4%. The AF phenotype of the patients - paroxysmal versus persistent, young versus old, short versus long history of AF does not predict fibrosis and so a young patient with paroxysmal AF may have extensive fibrosis and therefore a very high risk of arrhythmia recurrence whereas another patient, older and with persistent AF may have little fibrosis and therefore have a very good chance of long term success with AF ablation. The only clinical parameter associated with fibrosis was hypertension. These results suggest that imaging of patients with AF before recommending interventions might improve the management. Allowing us to avoid procedure that are unlikely to benefit patients and to offer them to those with much to gain. I predict that we will see a rise in imaging and tissue characterisation of AF patients over the next few years.  It usually goes like this. Mrs Jones is a lady in her mid-70s with a history of controlled hypertension. An irregular pulse is detected by a practice nurse usually during a routine blood pressure check. Atrial fibrillation is confirmed on an ECG and she is referred to cardiology outpatients. We go through the history, examination and then onto the management. I usually break this down into management of symptoms and reduction of stroke risk. In the asymptomatic patient the former is usually very easy so we rapidly move onto the latter which is usually more challenging. I explain that AF is associated with an increased risk of stroke. 10,000 people a year are admitted to hospital in the UK with a stroke and found to be in AF. Then we arrive at the moment of the consultation where the W word is mentioned. I have tried to introduce this gently using the word anticoagulation, talking about little clots in the heart, preventing them by thinning the blood but finally the W word has to come out: "So Mrs Jones I would recommend that we start you on Warfarin." A moment later the patient looks crestfallen. The reply is usually a combination of 1) I don’t want to go onto warfarin; 2) I have a friend/relative/neighbour who is on it and they have had terrible trouble; 3) I was dreading you would say that; 4) Can’t I just continue with the aspirin after all that thins the blood too doesn’t it? 5) Can I leave it for now and take it if things get worse. I usually ask the patient “What is your biggest worry?” and often the reply is: “I don’t want to have stroke!” We are recommending more and more anticoagulation. The awareness of the increased stroke risk associated with AF is rising and there are comprehensive guidelines recommending anticoagulation which apply to ever increasing numbers of patients. Anticoagulation in AF is now regarded by the pharmaceutical industry as big business. This made me consider the risks and benefits of different types of stroke prevention therapy for AF. Guidelines have made this easy. Calculate the CHADS2 or CHADSVASC score of the patient and if it is more than 1 for CHADS2 or 2 for CHADSVASC then anticoagulation is recommended. You don’t need to know or think about the absolute risk numbers just a simple addition. The guideline tells you when to start anticoagulation and of course if you follow the guidelines you can’t be criticised. On the other hand if the patient has a stroke and you didn't recommend warfarin then that is not good. If the patient has a serious bleed due to the warfarin then you can’t be criticised for following the guidelines, can you? Sometimes it helpful to think about the actual numbers behind these guidelines to see exactly the benefits and risks of the different treatments. It is common to tell the patient that anticoagulation reduces risk of stroke by two thirds - impressive. Consider Mrs Jones, she has an annual estimated stroke risk of 4.3% and an annual bleeding risk of 0.6% according to the risk calculators. Treating her with aspirin reduces the risk of stroke to 3.4% (22% RRR; 0.9% ARR, with a 1 in 106 chance of benefit per year). The risk of major bleeding rises to 1.1% (1 in 222 chance of being harmed). So a miniscule chance of benefit and miniscule chance of harm. Giving warfarin reduces stroke risk to 1.4% (66% RRR; 2.9% ARR, with a 1 in 35 chance of benefit per year) but the risk of major bleeding rises to 3.1% (1 in 40 chance of being harmed). If there are 1000 patients similar to this then by doing nothing 43 will have stroke and 6 of them a major bleed over the next year. Treat them all with warfarin prevents 29 strokes but cause 25 major bleeds. Treated them with aspirin prevents 9 strokes but cause 5 major bleeds. I guess it all depends on whether you fear stroke or bleeding more, major bleeding provided it is not cerebral haemorrhage is not usually associate with long term disability and so may be trying to compare apples with pears and remember the patients biggest fear was of having a stroke. The current recommendation is that anyone with a CHADS2VASC score of 2 or more should be offered anticoagulation. It is clear that warfarin treatment is associated with a benefit. As doctors we tend to emphasise the positives and stress the 66% risk reduction with warfarin compared to the 22% with aspirin. We do not stress the 5-fold increase in the risk of major bleeding associated with warfarin. There has been a huge interest in atrial fibrillation recently. Some of this has been driven by the availability of the new oral anticoagulant drugs and the intense advertising war between the different companies to position their drug as the most effective. This has also been accompanied by an awareness campaign to doctors regarding the stroke risk associated with atrial fibrillation as well as community clinics funded by the pharmaceutical industry intent on finding cases of atrial fibrillation and reviewing the anticoagulation treatment. As physicians we tend to play down the harmful effects of the treatments and emphasise the positives. We want to practice according to the guidelines. If you were the patient with AF and you were told you there was a 1:35 chance of benefit with warfarin and 1:40 chance of harm what would you do?  During the 1930's Karl Link was working to find out why cows were apparently dying from haemorrhage. He made the link between the bleeding problems and spoiled hay and in 1941 isolated an anticoagulant from the hay called dicumarol. This chemical reduced the clotting of blood and was highly toxic to rodents. Link assigned the patent on the chemical to the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, which patented the substance in 1948 under the name “warfarin” and began to market the product as a commercial rodenticide. Subsequently it started to be used to treat patients with heart problems to prevent blood clots. Although a number of warfarin like drugs were synthesized they are all vitamin K antagonists and for the last 60 years have been the only available oral anticoagulants. Warfarin has always been a difficult drug to prescribe and use in clinical having multiple drug and food interactions, complex pharmacokinetics and the need for close monitoring. Dosing is complex since the tablet taken today doesn't affect blood clotting until 48-72h later. Many patients are anxious if warfarin is recommnended by their doctor and they are usually reluctant to take the drug. This usually requires a great deal of explanation from the prescribing physician. However when warfarin is used carefully it is a highly effective medicine invaluable for patients when used in conditions such as atrial fibrillation, pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis. Warfarin also enabled valve replacement surgery to be performed with metallic valves which could never have otherwise occurred. If you were a pharmaceutical company looking for a blockbuster drug then developing a replacement for warfarin would have been pretty high up your agenda. In 2004 Ximelagatran was launched as the first orally available anticoagulant and was shown to be non-inferior to warfarin in the SPORTIFF III trial published in the Lancet. Ximelagatran underwent an extensive clinical programme which unfortunately showed significant liver toxicity when used for more than 35 days and because of this it was withdrawn. However In the last 2 years three more new oral anti-coagulants (NOACs) have been launched. Dabigatran is a direct thrombin inhibitor and rivaroxaban and apixaban are factor Xa inhibitors. Each drug has been investigated in a large clinical trial and compared against warfarin. In the trials it was shown that the NOACs were either more effective than warfarin (dabigatran at the 150mg dose) or non-inferior to warfarin (dabigatran at the 110mg dose, rivaroxaban 20mg and apixaban 5mg). The drugs are taken at a fixed dose and unlike warfarin do not need to be monitored with blood tests. Rivaroxaban is a once daily medicine whereas the others are twice daily. Dose adjustment is recommended in the elderly (>80 years) and the drugs are not suitable for people with severe kidney impairment but some can be used in moderate impairment. Clinical experience with these drugs is still limited and a number of questions remain. They do not affect the normal clotting tests undertaken in hospitals and so it is vital that patients inform medical staff if they are taking these medicines especially if they are admitted to hospital as an emergency. There are issues of compliance since blood tests are not required to evaluate the anticoagulant effect and what it is now know how significant the omission of one or two doses would be. It may be more complex to manage patients who bleeding whilst taking NOACs since there are no antidotes are currently available. There are still unknowns such as whether it is safe to cardiovert a person from atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm on a NOAC. There is data available from the RELY-AF trial subgroup and also recently a subgroup analysis from the ROCKET trial with rivaroxaban has been published but not trial has been done specifically to address this question. We are entering a new era of anti-coagulant treatment. There will always be a role for warfarin but I think we will see it used less and less as clinical experience with the NOACs grows. Much of this is currently being driven by patient choice and apparent ease of prescribing but we need to be cautious whiclinical experience with these medicines grows. RELY-AF Trial ROCKET Trial ARISTOTLE Trial RELY-AF Trial: Cardioversion Substudy ROCKET: Cardioversion Subgroup |

Dr Richard BogleThe opinions expressed in this blog are strictly those of the author and should not be construed as the opinion or policy of my employers nor recommendations for your care or anyone else's. Always seek professional guidance instead. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed